Prior to the Obama administration (2009-2016), these feature films should have, but almost never did, appear on all-time-best lists of American cinema. This is “counter-cinema” in the sense of “counterculture,” not necessarily part of a separate culture but made in a spirit of challenging the status quo. Each was considered fairly progressive upon release (however they seem now). Among the criteria: each film had to be at least an hour long, fictional (not a documentary), American in the sense that no other country could claim it (and centralizing at least one Anglo-American character), and streamable as of January 2024 (many great films are not). Welcome to 100 excellent, influential, and/or important milestones of diversity, inclusion, and intersectionality.

~

C1. Where Are My Children? (Weber, Smalley, 1916) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by CrashCourse read analysis by Stamp listen to my podcast

“…children should not be admitted to see this picture unaccompanied by adults, but if you bring them it will do them an immeasurable amount of good.”

What is the oldest surviving American feature film that was directed by a woman? Well, some say it’s 1916’s Where Are My Children? No director is credited on screen, but we know that the film was written, produced, and directed by the wife-husband team of Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley. Released by Universal, the production company is credited as Lois Weber Productions, something Weber insisted upon partly because she meant to attract other projects that were both socially relevant and formally daring.

Florence Lois Weber was born in 1879 in Pennsylvania, toured as a young singer, pianist, and evangelist, and worked as a repertory and stock actress for years until meeting the head of an acting troupe. Phillips Smalley, graduate of Harvard and grandson of Oliver Wendell Holmes, proposed to, and married, Lois when he was 38 and she was 25. Keeping her surname, Weber began writing spec scenarios for film companies. In 1910, Weber and Smalley started making short pictures and were hired by the New York-based Rex Motion Picture Company, where Weber wrote, acted, directed, edited, made sets, and sewed costumes. In 1912, Rex merged with four other companies to form Universal Film, prompting Weber and Smalley to move to Los Angeles. The merged company’s chief, Carl Laemmle, distinguished Universal from other studios by virtue of its female directors and producers. After Laemmle incorporated the Cahuenga Pass gateway from the valley to L.A. as Universal City, Laemmle encouraged Weber to run to become its first mayor, a job she was elected to in 1913. Weber barely had time for mayoral duties in 1914 as she directed 27 films, establishing herself as one of the industry’s most reliable, most interesting directors. In summer of 1914, Weber hired a new writing assistant named Frances Marion, and mentored her into the most prolific, best-known screenwriter of the silent era, male or female. Weber’s films became increasingly complex and layered, from The Jew’s Christmas to The Merchant of Venice to Hypocrites, the latter of which featured actually naked actresses to demonstrate the hypocrisies of religion and, well, encourage the kind of publicity that would draw both over-prurient audiences and over-prudish lawsuits.

The scenario for Where Are My Children?, written by Lucy Payton and Franklin Hall, was meant to capitalize on, but not plagiarize, the sensational stories around the obscenity trials provoked by Margaret Sanger’s work. Nurse Margaret Sanger was an activist alongside the likes of Emma Goldman and Upton Sinclair whose personal experience with fatally flawed family planning led Sanger to publish, in a socialist magazine, columns on sex education that evolved into her monthly newsletter, The Woman Rebel, in which she coined the term “birth control,” explained contraceptive methods in detail, and asserted every woman’s right to be “the absolute mistress of her own body.” By sending The Woman Rebel through the post office, Sanger provoked a 1914 over-prudish lawsuit in the form of her challenge to federal anti-obscenity laws, although the press around her trial seemed more interested in her estrangement from her husband, which is where Where Are My Children? more or less picks up.

Where Are My Children? begins with title cards forewarning that the forthcoming film is a fantastic idea but showing it to children is not. A card says “Behind the great portals of Eternity, the souls of little children waited to be born” to show abstract golden gates opening to smoke and clouds and columns and…maybe heaven? The next card says “Within the first space was the great army of ‘chance’ children. They went forth to earth in vast numbers.” We see a painting of dozens of Raphaelite angel cherub babies three times, the first adorned only by billowing smoke, the second laced by fire and brimstone after a card proclaims the “sad unwanted,” and the third glowing as a cross appears above them after a card hails a group sent forth “only on prayer.” Finally, the film’s first non-abstract imagery introduces us to eugenics believer and District Attorney Richard Walton telling a court that criminals are simply ill-born. Richard greets his wife, Edith, as she tends her dogs on a Versailles-like garden patio where a card says Richard “concealed his disappointment” over their lack of children, “never dreaming it was her fault.” Outside, Walton watches kids play, including his sister’s kid, and shakes his head with frustration. In court, D.A. Walton confronts one William Homer because of distributing his book “Birth Control,” from which Walton reads aloud the first sentence of Chapter Five: “When only those children who are wanted are born, the race will conquer the evils that weigh it down.” We flash to Homer’s experiences in slums, where one woman with a sick infant jumps off a bridge, and another woman physically battles her drunk husband. Homer’s Chapter 10 asks if “unwanted children should be born to suffer blindness, disease, or insanity?” A title card declares curtly, “A jury of men disagreed with Mr. Homer’s views.” After a bevy of blueblood ladies leave a lavish garden tea party, Edith murmurs to one that if she doesn’t want to be a mother, she might see Dr. Malfit, and soon Edith accompanies this woman to the doctor’s office, where Edith describes her friend’s condition as a “serious ailment.” We see those abstract golden gates close as a card discloses that an “unwanted one” has been returned so that a social butterfly can return to parties. The Walton mansion receives two guests, Edith’s rapscallion brother Roger and their housekeeper’s young adult daughter Lillian, whom Roger courts in the manner of “men of this class.” A month later, Lillian is pregnant, as symbolized by the golden gates opening and an abstract cherub angel alighting on the shoulder of Lillian, who agitatedly asks Roger for help, who turns to his sister Edith, who is coming to regret her previous abortions and reluctantly gives Roger the name of Dr. Malfit, who botches Lillian’s abortion. Lillian staggers out of his office, lies prostrate on the car ride home, wobbles out of the car, and collapses, discovered by the distraught district attorney. On her deathbed, Lillian tells her mother the truth, leading to an angry physical confrontation between the housekeeper, the Waltons, and Roger. Later, Walton comforts his housekeeper as she mourns over the intensely blue-lensed shroud of her dead daughter. Walton expeditiously brings Dr. Malfit to trial, but we cut from the courtroom to Edith’s common room where she sees, then burns, a letter that reads “Mrs. Walton, Call your husband off this prosecution or I will draw you into the case. Herman Malfit.” Edith asks her husband to go easy on Malfit, prompting Walton to forbid him bringing his books or other patients into trial. When the judge pronounces the sentence, fifteen years of hard labor, a bitter Malfit dumps his book in front of Walton and warns he should see to his own household. Walton opens Malfit’s book and learns the truth about Edith’s abortions. The Walton housekeeper, quitting and leaving, staggers past a society social of ladies, which Walton soon sunders by storming in and saying, “I just learned why so many of you have no children. I should bring you to trial for manslaughter, but I shall content myself with asking you to leave my house!” The women blow away, but not before some of them blame Edith, and after they’re all gone, Richard demands of Edith, “Where are my children?” As she breaks down sobbing, Walton laments, “I, an officer of the law, must shield a murderess!” Walton mourns his lost legacy and lost love at, uh, his beautiful stone fountain. Edith prays for pregnancy, but, as a card tells us, “having perverted Nature so often, she found herself physically unable to wear the diadem of motherhood.” The final title card says “throughout the years she must face the silent question, where are my children?” which cuts to a somewhat remarkable final shot of Richard and Edith sitting apart in front of their fireplace as ghostly kids come to snuggle with them and then Richard and Edith notably age, yet remain in place, as young adult ghosts visit.

It’s hard to disentangle the film Where Are My Children? from the contemporary politics of eugenics, a word that appears in many of Weber’s title cards. Sir Francis Galton coined the term eugenics in 1883, one year after his cousin Charles Darwin died, a date worth denoting because Darwin disagreed with Galton’s ideas about human-directed evolution. By the time Galton died in 1911, eugenics had become an academic discipline at many universities, the official policy of many governments, and a recommended methodology of many ministers. Eugenics gave scientific justification to ancient practices of infanticide of the disabled, and in practice, its focus on developing traits deemed desirable worked to legitimize racism. Today, from our esteemed universities that have each excised any eugenics departments, we commend the film Where Are My Children? for its anti-eugenics politics even as we wonder if it could have been a little less clamorously anti-choice. One could argue that Weber’s real target is wealthy women, or that Sanger’s position, as expressed by a man named Homer, gets its, ah, day in court…but the game is given away by the title, not Where Are The Children but Where Are My Children, as though the man has possessive rights to any progeny. Another factor is the nascent star system – Tyrone Power was the film’s star, whose privileges extended to getting his new-ish wife cast as Edith.

Stylistically, Lois Weber’s work on Where Are My Children? is utterly assured, moving breathlessly and confidently from plot point to plot point and from artistic scenery to theatrical spectacle. Weber certainly shared with Margaret Sanger a presumption that censorious officials’ attacks on her work would bring it more publicity, and indeed that plan worked well enough to result in packed houses in New York and New Jersey, but less well in Pennsylvania, where Where Are My Children? was banned for immorality. The one-two punch of Weber’s film Hypocrites and this film gave Lois Weber the reputation of America’s first female director.

Influenced by: Susan B. Anthony; prevailing, Griffith-era codes of style and decorum; Lois Weber is not credited as director but scholars have named her the film’s lead creative force

Influenced:Weber stood next to Griffith and Chaplin as one of the period’s most influential directors

~

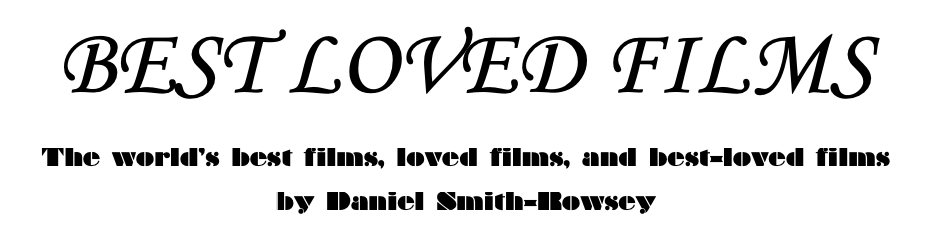

C2. Within Our Gates (Micheaux, 1920) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on criterion watch analysis by Robertson read analysis by Brundage listen to my podcast

“It is my duty and the duty of each member of our race to help destroy ignorance and superstition.”

Before turning 25, Micheaux worked as a marketer, a stockyard hand, a shoeshine boy, and a Pullman porter, the latter granting the gregarious gentleman grace to meet many sorts of men and to travel West, where he used two thousand dollars he’d saved to buy land in South Dakota and work as a homesteader. Micheaux wrote letters to at least 100 of his African-American friends to encourage them to join him at farming, but only his brother ever took him up on it. At the age of 29, in 1913, Micheaux used his pastoral profits to publish a thousand copies of a biographical-ish novel he wrote called “The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer,” and walked around South Dakota and Chicago selling his book to friends and acquaintances and strangers.

After years of producing more modestly profitable grain and novels, in 1918, Micheaux received a letter from the Lincoln Motion Picture Company; after many negotiations throughout 1918, Micheaux decided he would ask his network of supporters for money for him to direct The Conquest into a film. Retitled The Homesteader, the film is about a Black farmer who resists many white women out of race loyalty while having terrible difficulties with his Black wife, eventually leading to her patricide and suicide and her husband being blamed for both. Released in 1919, considered the first feature directed by an African-American, The Homesteader did decent business amongst carefully targeted Black communities throughout the Northeast. Sadly, Micheaux’s first feature is now thought to be a lost film. We are lucky enough to be able to watch his second feature, the oldest surviving film directed by a Black person, Within Our Gates.

We don’t know much about the production of Within Our Gates other than to say it was made very cheaply, with actors barely paid, no reshoots allowed, and sets, costumes and props liberally borrowed and re-used. That said, the film condenses so much information into every minute that it never feels repetitive or overdrawn.

Within Our Gates begins with a title card placing us “in the North, where the prejudices and hatreds of the South do not exist – though this does not prevent the occasional lynching of a Negro.” Sylvia Landry, a Southern mixed-race schoolteacher, on a visit to Boston to her cousin Alma Prichard, reads with her a letter from Canada, dated June 1920, from Sylvia’s fiancé Conrad whom Alma secretly loves. Alma eavesdrops as her stepbrother Larry tries to court Sylvia, who tells him she doesn’t love this Larry whom titles tell us is also known as “The Leech,” is on the loose, and is a “notorious member of the underworld.” Alma intercepts a telegram from Conrad intended to inform Sylvia of his Thursday arrival in Boston before the army ships him to Brazil. A cheating scam in a poker game ends in a shootout where Larry kills a player named Red…which turns out to be Sylvia’s dream…or was it? Upon Conrad’s arrival, Alma tries to seduce Conrad who rushes to Sylvia’s bedroom only to find, thanks to Alma’s machinations, Sylvia in the arms of a white man. Conrad starts to strangle Sylvia, sighs “I loved you so!” and skedaddles. Now fifteen minutes into the movie, a title card takes us to “the depths of the forests of the South, where ignorance and the lynch law reign supreme, we find the hamlet of Piney Woods and the school for Negroes.” We meet Reverend Wilson Jacobs, “founder of the school and apostle of education for the black race,” alongside his sister Constance, as they meet Sylvia applying for a job. Later, Constance tells Sylvia that Wilson can’t bear to turn pupils away, but the state doesn’t provide enough for Negroes and they’ll have to close if they don’t get $5000. Sylvia tells the Reverend that it is the duty of “each member of our race to help destroy ignorance and superstition,” so she’ll go up north and try, with God’s help, to raise the money. In Boston, Doctor V. Vivian looks out his window, sees a thief mugging Sylvia, runs to cut off the thief, collars him, hands him over to a cop, hands Sylvia back her purse, and returns with her to his office for a pleasant chat. A rich racist, Geraldine Stratton, nods while reading an article quoting anti-Black-suffrage Senator Vardeman (who is real) saying “from the soles of their flat feet to the crown of their head, Negroes are, undoubtedly, inferior beings.” A week into fruitless fundraising, a fretting Sylvia gets flattened by a car carrying one Elena Warwick, who helps bear Sylvia’s body to the car. Elena interviews Sylvia in the hospital where Sylvia shows Elena a telegram from Jacobs saying the school will need to be closed in ten days. On Elena’s invitation, Sylvia visits her mansion, where Elena professes to be interested in her race and promises to help the school however she can, but when she asks her Southern friend Geraldine for advice, Geraldine laments “Can’t you see that thinking would only give them a headache?” Instead of granting Sylvia $5,000, Geraldine recommends giving $100 to a Black preacher named Ned, whom we see made up like a devil animatedly telling his nodding congregation, “The white folk, with all their schooling, all their wealth, all their sins, will most all fall into the everlasting inferno! While our race, lacking these vices and whose souls are more pure, will most all ascend to heaven!” Later, when two of Ned’s old racist white friends show him the article about Black voting, Ned bows his head, shuffles his feet, smiles sheepishly, and tells the whites his sermons always say “this is a land for the white man and Black folk got to know their place.” As Ned leaves them delighted, Ned says only to himself, “Again I’ve sold my birthright…As for me, miserable sinner, Hell is my destiny.” Geraldine apparently convinces Elena, who horrifies Sylvia in their next meeting, as she knows, as we see, Jacobs is receiving her telegram message to keep the school open because funds are coming. This is a misdirect, because Elena re-meets with Geraldine to tell her that based on what she said, instead of giving the school $5000, she’s going to give the school $50,000. After Dr. Vivian dreams of Sylvia and Sylvia dreams of Dr. Vivian, the two meet and hold hands warmly just before she returns to the South, where Reverend Jacobs proposes marriage and Sylvia refuses, venerating vivacious Vivian. On the lam, Larry the Leech locates the lavishly funded school, corners Sylvia on a bench, and tells her to steal from the school or he’ll tell everyone what sort of person she really is. Sylvia hits him, calls him a liar, storms off, cries alone, comes to a decision, and leaves the school in a torrential rain. Larry returns to Alma’s where a cop finds him, mortally wounds him, and prompts the arrival of Dr. Vivian, who learns from Alma that her cousin Sylvia was raised by the long-ago lynched Landrys. Alma confesses the casuistic cuckolding of Conrad, and we cut to a title saying “Sylvia’s Story” in a deep forest of the Gridlestone estate. Jasper Landry, uneducated and disenfranchised, lives on the hope of an education for his kids, hangs out at a kitchen table with his wife and Sylvia, and finds they have just enough saved to send Sylvia and Emil to school. We meet the rich white patriarch Gridlestone, a “modern Nero,” and Efrem, his shifty servant, “an incorrigible tattletale,” who warns his master of the insecurity of Sylvia sensing his swindles. On rent payment day, Jasper and Gridlestone argue angrily as, outside the window, a disgruntled white farmer shoots dead Gridlestone knowing Landry will be blamed for it. After Efrem spreads this fiction around the town, a hillbilly-looking lynch mob develops into a weeklong manhunt as the Landrys leg it into the large forest. Two yokels accidentally assassinate Gridlestone’s actual killer as Efrem laughs at these forest escapees compared to him sitting pretty with whites, a laugh that arouses the anger of the hayseeds. A newspaper calls Efrem a “recent victim of accidental death at unknown hands,” while expressing Efrem’s version of events, a fabrication we watch enacted as a cackling plastered Jasper blasts shot after shot at Gridlestone. A title card reads in full, “Meanwhile, in the depth of the forest, a woman, though a Negro, was a [all caps] HUMAN BEING.” A tired fugitive, Jasper’s wife wonders how long before justice arrives, with more all caps reading HOW LONG? The lynch mob belatedly locates the Landry parents, hang them with nooses, and sets their bodies afire, which is cut with an old white Gridlestone brother attempting to rape Sylvia in a far-off safehouse. As the violence becomes more vicious, we cut to Vivian hearing the narration of Alma, whose dialogue card says “A scar on her chest saved her because, once it was revealed, Gridlestone knew that Sylvia was his daughter – his legitimate daughter from marriage to a woman of her race – who was later adopted by the Landrys.” Alma explains that the brother didn’t explain himself to Sylvia, stopped hurting her, started helping her, and paid for her education. Somehow, Dr. Vivian finds Sylvia and somehow says, “Be proud of our country, Sylvia.” Vivian mentions Roosevelt in Cuba and soldiers in Carrizal and World War I. He tells her, “we were never immigrants!” He says he knows of Sylvia’s hard feelings, but “In spite of your misfortunes, you will always be a patriot – and a tender wife. I love you!” Sylvia goes with this all the way to a wedding canopy when a title says “The End.”

The Johnsons and Micheaux had argued about The Homesteader blaming Black people for their problems, and so there’s a slight irony in the fact that, after Micheaux had found success without them, he went on to make a film with the reformist values the Johnsons wanted. Despite the ubiquity of D.W. Griffith’s blockbuster The Birth of a Nation, Micheaux didn’t want Within Our Gates read only that way; despite Micheaux’s protests, it often is. Both films have an overarching structure of a North-South marriage that might re-bind the country in a manner that the writer-director considers, uh, enlightened. Within Our Gates’ rich, racist, anti-suffrage lady resembles the Lillian Gish character from Griffith’s film, here transformed from a heroine into the villain. Birth of a Nation culminates in innocent whites fending off a home invasion by Black savages; Within Our Gates culminates in Sylvia fending off a home invasion and rape by a savage rich white man, a scene intercut with a lynch mob hanging two innocent Black people and burning their bodies. Local censoring boards singled out these two vignettes, particularly in the wake of what were called “race riots” in the summer of 1919 in many American cities especially Chicago. That summer of white violence against Blacks was its own sort of reaction to the validation given to the Ku Klux Klan by The Birth of a Nation, which was still playing to packed houses in 1919 four years after its release. Micheaux explained he was reacting not only to Birth of a Nation but to everything: Jim Crow laws, suffrage, the Great Migration, peonage, Black criminals, and especially the savagery and hypocrisy shown by whites against Black people. Reacting to the Chicago board, Micheaux did make a few superficial cuts, but chose to premiere Within Our Gates in Chicago anyway, where it began doing reasonable business in carefully targeted theaters in urban America – the sort of theaters where whites rarely ventured. Ronald J. Green felt the title “Within Our Gates” was a warning to white marauders coming into Black communities, although it can also be read as a proto-for-us-by-us solidarity.

Influenced by: The Birth of a Nation; W.E.B. DuBois-era literature, resistance

Influenced: Micheaux created the “race film” (made for and by black people), which would remain a minor and low-budget subgenre until about the 1950s

~

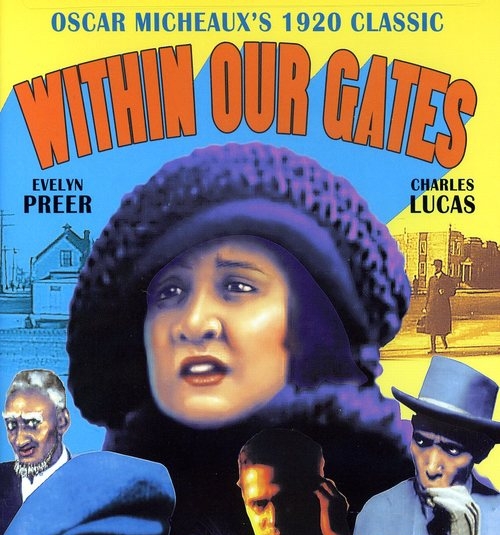

C3. The Sheik (Melford, 1921) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Bunhead read analysis by Hammond listen to my podcast

“When an Arab sees a woman that he wants, he takes her.”

The man renamed Rudolph Valentino would later credit June Mathis for “discovering” him as she cast him as tango-dancing Argentinian Julio Desnoyas in Four Horsemen, but other than Mathis, the rest of Metro found Valentino hard to work with and shunted him into smaller roles for the rest of his four-movie contract. In 1921, Rudolph Valentino moved to Famous Players-Lasky, where Jesse Lasky had many things ready to go: a distribution deal with Paramount, a marketing plan, a star named Agnes Ayres, and a script based on Edith Maude Hull’s novel “The Sheik,” which surprised Hull and the publishing world by becoming a best-seller upon its 1919 release.

A bit more about that marketing plan: the film’s poster already appeared as we now see it, with a photo of only Ayres in a pith helmet smiling on the sands, and her name above Valentino’s, despite his recent notoriety for Four Horseman of the Apocalypse. However, Valentino knew he was getting the title role and a plan to begin marketing him as “The Latin Lover,” a brand-new coinage. Oh, about that plot: in Hull’s novel, the Sheik clearly rapes Lady Diana, but Lasky had no intention of beginning his relationship with Valentino quite so sordidly. To that end, Lasky hired reliably pliable director George Melford, who had a somewhat interesting career that doesn’t require detail here. As for Edith Maude Hull, she never expressed regrets about her novel’s celebration of misogyny, only saying she regretted selling the film rights for too little to Lasky.

The Sheik begins with camels and desert canopies and oasis markings and praying Arabs in tunics and a title card saying “where the children of Araby dwell in happy ignorance that civilization has passed them by.” Another card introduces us to “maidens chosen for the marriage market – an ancient custom by which wives are secured for the wealthy sons of Allah.” We meet the young Sheik Ahmed Ben Hassan smiling broadly while granting a desperate chief an exception to losing his daughter to the market. A title card reads, “On the way to the harems of the rich merchants, to obey and serve like chattel slaves.” Drinking tea at a souk in Biskra, a real city in Algeria, wealthy white women disapprove of Lady Diana Mayo’s “wild scheme” of a tour into the desert “with only native camel-drivers and Arabs!” We meet Lady Diana and her brother, Sir Aubrey, who fails to persuade her to call off her adventure. At an evening party in Biskra’s “Monte Carlo,” Arabs perform with prancing ponies and upcast spears as a young tuxedo-clad man begs Diana to remain with him, to which she answers, “Marriage is captivity – the end of independence. I am content with my life as it is.” Sheik Ahmed enters, commands his retinue into the casino, and shares a brief warm eye contact with Diana, who is told, by a white guy, that the casino is Arab-only. When she objects to such savage rules the white guy objects that the Sheik is no savage, but a Paris-educated Arab. Diana sees a belly dancer performing, returns to her room, and instructs a servant to bring the dancer to her room whereupon Diana obtains the woman’s full uniform. Veiled, Diana sneaks into the casino to observe a belly dancer performing for the sheik and other bidders, but when a host grabs Diana by the hand, we’re misdirected into believing we’ll see Diana perform and/or sold as chattel. Instead, the Sheik inspects Diana, rips off her veil, and smiles broadly while declaring to his fellows, “The pale hands and golden hair of a white woman!” (Agnes Ayres’ hair is brown throughout the film.) The Sheik removes Diana’s outer burka to reveal her ornate bedlah and a gun she is pointing at him, causing him to grinningly ask who invited her, to which she answers she wanted to see the savage that would keep her from the casino. The Sheik cheerfully bops the burka back on Diana, asks if he the savage can escort her to the door, sees her off, and hears from one Mustafa Ali that he is booked to escort her to the desert. At dawn, not unlike in Disney’s Aladdin seven decades later, Sheik Ahmed scales her balcony and hops into her chambers, in this case to creepily watch her sleep before escaping, awakening, and serenading her with a song about loving pale hands. In pith helmets, Diana and brother Aubrey ride horses into the desert until she tells him she’ll see him in a month in London, and roughly a second after he absconds, Mustafa smirks as he signals a score of soldiers on horses who storm over the hill and induce Diana to panic, flee the other way, shoot back at them, and drop her pistol. Sheik Ahmed leads the posse, sidles up alongside Diana, jumps onto her horse, grabs her, and says “Lie still, you little fool!” as the regiment, rejoicing, raises its rifles. A card says “Her exultant dream of freedom ended – a helpless captive in the desert wastes.” In the Sheik’s desert village, Diana delivers a defiant glance as Ahmed walks her into his massive tent complex and introduces her to Zilah, her barefoot female servant, as well as Gaston, his be-suited French valet who is told to attend to Diana’s every need. When she asks why he brought her here, he smilingly replies, “Are you not woman enough to know?” Ahmed leads her into her private room and disparages her pants, saying it wasn’t a boy he saw in Biskra. Diana tries to escape in a strong sandstorm, but the Sheik brings her back inside to be rewarded by her blade, at which he laughs, disarms her, and claims he could make her love him. Later, Diana cries at her bed as Ahmed comes in, clearly considers clutching her by force…and then reconsiders and cuts out, in a colossal change from Hull’s novel. Zilah enters and gives Diana a comfort hug and an uncomfortable burka to wear. Sheik Ahmed is thrilled to learn of a coming visit from his novelist friend Raoul from Paris, but when Diana distresses of Raoul discovering her in Arab accoutrements, Ahmed arranges for her attire to return before he returns from Biskra with Raoul. Seeing her joy, Ahmed attempts a goodbye kiss only to see her distaste so he says “You hate them so much – my kisses?” While the Sheik is in Biskra, on an excursion with Gaston, Diana fools him into dismounting, hits his horse, and escapes. Elsewhere, Ahmed winsomely warns Raoul not to be bewitched by Diana, Raoul replies “Does the past mean so little to you that you now steal white women and make love to them like a savage?” Ahmed thinks, smiles, and responds, “When an Arab sees a woman that he wants, he takes her!” A caravan of bandits led by the villainous Omair almost seizes the runaway Diana, but Sheik Ahmed’s entourage arrives in the nick of time to save Diana’s life. After a shared dinner between Diana, Ahmed, and Raoul, the latter pulls aside the Sheik to remand him for “the humiliation of meeting a man from her own world.” With Diana and Raoul dressed for British high tea, Diana returns to Raoul the rough draft of his manuscript with praise and skepticism that his novel’s heroic man can be found anywhere as an eavesdropping Ahmed despairs of her antipathy…until an assistant runs up to Raoul for medical help and Diana’s cry of “Ahmed!”, though mistaken, proves her affection. Ahmed prepares to leave Diana with Gaston, asks her not to run away again, warns of Omair, returns to her her pistol, and confides that he trusts her. On the road, Raoul tells Ahmed that Diana is a liability that he could escort back to Biskra, causing the Sheik to laugh that Raoul wants her too before admitting that making her suffer isn’t giving him the pleasure he expected. Raoul ripostes “Because you love her” as the films cut to Diana in the desert lazily writing “Ahmed I love you” just before she and Gaston are attacked by Omair, Mustafa, and their fellow marauders. Diana and Gaston hold them off until most of their ammo runs out, when Diana asks Gaston to kill her rather than let her be captured, but just before Gaston pulls the trigger to kill her, someone else pulls his and kills Gaston. After Omair takes Diana away, Sheik Ahmed shows up and scans her words somehow preserved in the sands. In a room in Omair’s gargantuan stone palace, Diana gets roughed up by Omair’s noticeably darker servants until they are interrupted by Omair’s assistant who has been told to “bring forth the white gazelle.” In disturbing imagery, Omair assaults Diana, who futilely fights back…when Sheik Ahmed’s battalion storms the palace. The Sheik and Omair fight man to man, and both men seem mortally wounded. Back at the Sheik’s village, while praying “Tribal hearts appeal to Allah,” Diana states that the sleeping Sheik’s hands are small for an Arab’s, to which Raoul replies, “He is not an Arab. His father was an Englishman, his mother a Spaniard.” Raoul tells Diana that the former Sheik found Ahmed abandoned by his parents, raised him, sent him to Paris, and died with the arrangement that Ahmed would return from Paris and lead the tribe. Ahmed wakes up and embraces an affectionate Diana as a praying Arab outside gets the final word: “All things are with Allah!”

The Sheik was absolutely understood to be problematic at the time, which was part of its appeal, perhaps comparable to “50 Shades of Grey.” Several critics took issue with the removal of the novel’s rape because it turned the story into a sort of regressive wish fulfillment for 19th-Amendment-resisting men and women. As with 50 Shades of Grey, these audiences came out in droves, turning The Sheik into a substantial hit for Paramount in 1921 and 1922. Metro’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, in which Valentino plays a tango-dancing Julio, remained in theaters at the same time as both films were among the early 20s’ highest earners. Valentino would never again be second-billed or not pictured on the poster. June Mathis, then Metro’s first female executive, broke her Metro contract to join Valentino at Paramount, become Hollywood’s highest-paid executive of any age (she was 35), and put Valentino in more Latin-lover-flavored leads, beginning with being a bullfighter named Juan Gallardo in Blood and Sand.

The Sheik was by far the most influential silent film regarding two important ethnic groups, Arabs and Latinos. Scimitars and sand tents had certainly been seen on screens before, but maybe because Britain lost most of its Muslim holdings including the nation newly called Turkey, The Sheik rode or set off a wave of cultural appropriation-slash-appreciation that could be heard in popular songs, seen in new architecture, or just noticed every time the press covered Jazz Age parties using words like “harem” and “sultan” and “sheik.” Every studio found space for an apparently Algeria-analogous area of the backlot to support the suddenly successful sub-genre, including United Artists’ and Douglas Fairbanks’ 1924 film The Thief of Bagdad, which pioneered several effects as well as the fledgling career of Anna May Wong. Arab culture was treated with both reverence and revulsion, something that would trickle down to Hollywood’s eventual portrayals of Arab-Americans, which comes up in much greater detail later in the C-list. For now it’s enough to say that in the 1920s, Muslim/Arab culture was both regarded and disregarded, which is something we now also say about the “Latin Lover” archetype. To modern sensibilities, the awkward appropriation of Arabia may sound far removed from the term “Latin Lover,” but in fact, Latin didn’t yet mean Latin American or Latino. When newspapers of the 1910s spoke of Latin influence, it referred to languages that derived from Latin, including Italian, Spanish, and French, not excluding the French that was Algeria’s official language; Latin and Mediterranean were often used interchangeably. Of course, it’s true that the Italian Rudolph Valentino was not what we now call Latino, but it’s not true that in 1921 Italian-Americans had anything like the white privilege they could assume a century later. It’s not only that Italian-Americans were then regularly described with epithets like “dago,” “wop,” and “guinea,” the latter an association with kinky hair that sought to equate Italian- and African-Americans. Official prejudice against Italian-Americans went all the way to the top, to the State Department that forced Italy to accept restrictive emigration protocols, and to Congress, that passed the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 which rolled back the Italian immigration rate to the group’s percentage of the population in 1890, essentially defining Italian-American as non-white even as Valentino had arguably become America’s biggest movie star.

Influenced by: colonialist ideas about Arabs and white women, though the novel’s rape scene was removed

Influenced: Latin Lovers, “sheik” as a very popular type/name of the period

~

C4. Body and Soul (Micheaux, 1925) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Glover read analysis by Blakeslee listen to my podcast

“You white-livered, lying, hypocritical beast – to steal my poor mother’s money!”

Body and Soul is sometimes called Micheaux’s masterpiece; it’s the only one to survive with all its original title cards, though that may be partly because it starred and debuted a 27-year-old future star and anti-racism activist named Paul Robeson. There have been no fewer than three big-budget bio-pic feature films about Valentino, but so far none about Robeson, despite, ahem, the following.

Robeson’s father William was a slave who escaped in his teens to, eventually, Princeton, New Jersey, where he became a church minister and fathered Paul in 1898. In 1915, Robeson became Rutgers third, and then-only, African-American student, where he went Phi Beta Kappa while collecting awards in debate, singing, basketball, track, and football, the latter including first-team All-American as a junior and senior. After Robeson’s classmates elected him valedictorian, his address was not unlike some of his winning debate oratories in that it questioned Black soldiers fighting in the Great War while being denied commensurate opportunities at home and exhorted the audience to fight for equality for all Americans. In the early 20s, Robeson attended law school, sang at the opening of the Harlem YWCA, and began his, yes, career with the National Football League, playing for the Akron Pros in 1921 and the Milwaukee Badgers in 1922 before quitting football, finishing law school, starting as a lawyer, and quitting law because of structural racism. In 1921, Robeson married Essie Goode, who encouraged him to pursue theater, where he landed several theatrical roles to the point of Eugene O’Neill asking for him, and soon, not unlike June Mathis, Essie Robeson negotiated and arranged for Paul to star in dual roles in his film debut.

In the five years between Within Our Gates and Body and Soul, Oscar Micheaux somehow wrote and directed ten films with mostly African-American casts. By 1925, the press referred to his movies as “race films,” a term that his distributors encouraged because it drew Black audiences to his movies. By 1925, Micheaux had already adapted the seven novels he’d written before making his first film, but he well knew how many more African-American stories had never been seen onscreen. Micheaux had a plan for a Black Priest and the Pauper, if you will, and when he learned that Eugene O’Neill’s favorite Black actor was the son of a preacher man, he only needed to know if Robeson could risk offending his father. Robeson replied that his dad was dead and Robeson would be proud to play a false prophet. New York State, however, claimed the “immoral” and “sacrilegious” result would “tend to incite to crime” and Micheaux wound up making many cuts before the film’s exhibition. Based on the trenchant testimony that sustains, I would have loved to have seen what New York State saw.

Body and Soul begins by introducing us to Reverend Isaiah Jenkins, “Jerimiah, the Deliverer” – “still posing as a Man of God,” as a newspaper article confirms. A “Negro in business,” Rogers, welcomes Jenkins into a Prohibition-prohibited speakeasy where Jenkins samples and approves of Rogers’ liquor. A cut to two women seems at first like a mistake, but I ask you to put a pin in that moment. Speakeasy proprietor Rogers informs Jenkins that he normally asks for payment, but he’s a Reverend…who pockets a full flask of moonshine and successfully demands payment from Rogers if he doesn’t want to hear about his speakeasy in a sermon soon. As the drunk Jenkins staggers home, we return to the house of the women as mother Martha takes savings money out of a Bible, sits in her chair, and sleeps. Her young adult daughter, Isabelle, awakens at 1:30am to see her mother stressing over a dream, standing, stashing the cash back in the big Bible, stuffing the book in a dresser drawer, and shoving into bed. “Yellow-Curley” Hinds of Atlanta arrives in Tatesville and proceeds to Rogers’ speakeasy, where Rogers charges Hinds to check out Jenkins’ church. On Sunday morning, while preaching from the pulpit, Jenkins spies Hinds in the pews and flashes back on the prison time they shared together. In a private room, Hinds tells Jenkins he isn’t looking for him, but instead for girls for “Cotton Blossom’s Shoulder Shakers” like, say, Isabelle. Jenkins’ dead-ringer look-alike, Sylvester, courts Isabelle, who brings him home to get her mother’s permission for them to marry. Martha refuses permission, casts out Sylvester, and insists that Isabelle should marry Jenkins, whom Isabelle calls a drunkard and a sinner, calumnies that cross-cutting confirm. Amidst photos of Booker T. Washington on the walls, Martha promises Isabelle a fortune if she marries her pastor, but upon her continued refusal, the mother calls the daughter an ungrateful sinner and pushes her down on their bed. With Isabelle gone courting Sylvester, two neighbors come calling in frilly Sunday clothes, Sis Caline and Sis Lucy, who are soon joined by Reverend Jenkins. When Isabelle returns home, Martha offers her daughter to the preacher, who prompts the prissy ladies to leave so that he can save this young woman’s soul. Isabelle refuses Jenkins and opens the door to hug her mother, upon which Jenkins blames her attitude on the devil, his “no-account brother,” and Martha for “letting this child become worldly.” After Martha closes the door on them again, Jenkins literally twists Isabelle’s arm followed by an ominous title card with one word, “Later.” Martha re-enters to see her stiffly standing daughter and smiling Reverend, who saucily sounds off, “It was a great struggle, Sister Martha; but the Lord’s Will be done. He won.” As Martha clutches a shell-shocked Isabelle, Jenkins shouts, “And now as I must carry his work into the byways for other sinners, I’ll be moseying along.” With him gone, Isabelle cries in the arms of Martha, who makes many wrong guesses about what’s bothering her daughter, and title cards bring us inside her thoughts, “something vague, disquieting, bewildering – but of course, it was only the work of the Lord!” Believing Isabelle wants fresh food to cheer her up, Martha goes to the store, buys some, runs into Sis Caline and Sis Lucy, and laughs with them as we cross-cut to a disconsolate Isabelle packing up all her possessions, writing a note, feeling “crushed – body and soul,” leaving home, stumbling around lost, and boarding a train. On the street, Jenkins runs into Yellow-Curley Hinds, who lost money to Rogers and demands some from Jenkins, who refuses only to be threatened with exposure as a faker. At the speakeasy, when Hinds accuses Rogers of rigging all of his games, Rogers grumbles “Mah money, mah liquor” as he pays Jenkins who gives some to Hinds. Martha returns home with Sis Caline and Sis Lucy, aims to show them Isabelle’s dowry, opens the Bible, gets stunned to find it cash-less, and finds the note reading: “Dear Mama, I have taken your money and am running away. Don’t attempt to follow for I shall hide. Please try to forget your heartbroken daughter, Isabelle.” In a very appealing modern Atlanta, Isabelle ambles her suitcase into a very unappealing alley near Decatur Street. Months later, in the same Atlanta neighborhood, Martha spies on a pitiable Isabelle as a stranger takes pity upon her by buying her some street food. Martha follows Isabelle to her small apartment, knocks on her door, opens it, says “Mah baby!”, embraces her daughter, sits down with her, and continues to rebuff any bad beliefs about Jenkins. Isabelle says she never took any money, knew her mother wouldn’t believe her, but “the time has come when you must hear my story.” We flash back to Jenkins driving Isabelle in a horse and buggy through a forest in a fierce rainstorm that stops their buggy, starts the horse to run away, and strands the pair wandering in circles until they find a deserted, multi-room cabin. Inside, Jenkins leaves Isabelle at a fireplace to dry her wet clothes, but after she undresses, he returns with a lustful look and a title card telling us “half an hour later” before he leaves. Back in the present, Isabelle explains that all things considered, Sylvester understood her best, but when Mama refused to let her marry him, that opened the door for more of Jenkins’ assaults. We flash back to an extended version of the arm-twisting scene, with Jenkins contorting Isabelle’s limbs until she finally confesses, and draws from, the stash of the secret savings. Complex extreme close-up cuts between cotton, a kitchen iron, and the cash. Isabelle and Jenkins each accuse the other of stealing the money, but he adds that Martha will never believe her daughter, and so he’ll “be moseying along.” Isabelle makes one last lunge for the lucre, but he knocks her to the floor while boasting Martha won’t believe that either. When he advises her to gather her things for the 4:30 train to Atlanta, she protests she doesn’t have a cent, and so he gives her ten dollars just before Martha returns. Back in the Atlanta apartment, Martha accepts Isabelle’s truth and cares for Isabelle as she lies in bed, lapses into severe illness, and looks…at a divine presence? A title card says “Reverend Jenkins had promised to preach that sermon which is every black preacher’s ambition – ‘Dry Bones – in the Valley.’” In the Tatesville church, the happy townspeople, including Sis Caline and Sis Lucy, gather, tithe, and cheer as Jenkins orates “Dry Bones” so drunkenly and raucously that he repeatedly punches one of his assistants, who touches his bleeding nose and says “Hallelujah!” The church party stops upon the entrance of Martha, who reports having just come from an Atlanta funeral, continuing with a card reading “Yes mah brudders an’ sistahs! Isabelle is dead – and there stands the man who killed her!” The congregants believe Martha and converge on Jenkins with fury, but he manages to escape. That night, as Martha tries to rest at home, a bedraggled Jenkins staggers in her door, begs her for mercy, and pleads, “you coddled me – and you – ruined me!” When they hear a door knock, Jenkins tells Martha that with her prayers she can now save him. Jenkins hides as Sis Caline and Sis Lucy enter, tell Martha a police bloodhound led them here, and somehow fail to convince Martha to reveal him. Jenkins crawls away, hides in the woods, and beats to death an approaching vigilante. In her chair, Martha rests, opens her eyes, and sees Isabelle and Sylvester enter with a title card telling us “All a dream – only the night-mare of a tortured soul!” Isabelle beams, “Oh, mama! Sylvester’s discovery has been accepted, and he is to be paid three thousand dollars, advance royalty, in sixty days!” Martha hugs Isabelle as the kind-hearted Sylvester looks on sheepishly. Martha goes to get Isabelle’s dowry from inside her hidden Bible, sees that it’s where she expected, and faints with happiness into the couple’s arms. In a brief coda, the happy, smartly dressed couple return to Martha’s “Home again after a honeymoon up North.”

Let’s be clear that some films are renowned for the effect they had right away, like The Sheik, and others are here for their larger legacy. Oscar Micheaux’s films were mostly unseen and unknown to studio moguls of the silent era. Only later did they take their place as some of the best films of the period…whether or not critics have placed them on their all-time lists.

Body and Soul is either a scathing critique of church-sanctioned corruption and violence and rape, or, uh…all a fanciful fantasy? Normally, I’m not a big fan of the “it was all a dream” school of filmmaking, but Body and Soul is more complex than that. We saw Martha awaken in her chair in the second-to-last scene, but when exactly did Martha’s dream begin? We first saw Martha sleeping in her chair about 7 ½ minutes into the film, with her daughter nudging her into awakening and gasping “Ah done had a ter’ble dream!” But do you remember me telling you to put a pin in that glimpse of Martha and Isabelle before we knew who they were? In fact, we saw seven minutes of action before Martha sat down in her chair to sleep…suggesting that that action may well have been real. That suggests that Sylvester, or someone looking a lot like him, really did lean on the speakeasy proprietor for corrupt kickbacks. Instead of reading Body and Soul as merely a fever dream about disbelieving one’s daughter’s tale of assault before happily marrying her to a nice young man, I prefer to see that young man as having some of the darker side we so exhaustively saw. After the way Micheaux showed Robeson’s ruthless side for an hour, it’s hard to easily buy him as a sheepish angel.

Influenced by: Micheaux’s remarkable ambition and perspective on many parts of society

Influenced: Robeson became a star and eventually an almost Marcus Garvey-like figure, but this film was mostly only seen by Black people, codifying the “race film”

~

C5. Ramona (Carewe, 1928) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by comicpencil read analysis by Worden listen to my podcast

“Your mother was an Indian. Your father was a white man. He married her after my sister refused him.”

Helen Hunt Jackson’s very popular novel “Ramona,” published in 1884, had already been adapted into two films, the first a short directed by D.W. Griffith in 1910, but Edwin Carewe had several personal reasons to make what came to be considered the canonical Ramona. For one, American audiences had demonstrated their empathy with Native Americans, most recently with the 1925 hit film The Vanishing American, and Carewe felt that within the confines of soapy melodrama, he could create at least one scene that showed the true brutality and violence of white settlers against Natives. Another reason was that Carewe saw certain parallels with Jackson’s story and his and Dolores Del Rio’s actual life. Del Rio was born with mixed ancestry and grew up under wealthy, yet reduced circumstances, much like the novel’s Ramona. When Carewe met Del Rio, she was living with an attractive man and a mother figure, just like the novel’s Ramona, and he was instantly smitten with her, just like Alessandro, the Native American co-lead of the story. (Jaime was 18 years her senior, Edwin all of 21.) In Jackson’s novel, Alessandro waits, then spirits away Ramona, at first to a village, then high up in the California hills where her former friend can’t find her. Carewe spirited Del Rio as far as Hollywood; maybe if he kept making movies with her, he could convince her to leave Jaime and join him in the high hills. Carewe might have even played Alessandro, but UA demanded a star, and found Warner Baxter, a white guy who, in Valentino’s wake, had steadily been playing Latin Lovers, yet wasn’t dark enough for a Hollywood Injun and so realized the role in repulsive redface.

Working with his brother, screenwriter Finis Fox, Carewe wound up mostly removing the novel’s elements of conflict between Mexicans and Americans. The novel justifies Señora Moreno’s anger because the white American invaders have cut up her land; in the movie, she’s an evil Spanish aristocrat with contempt for her brown employees, more like the malicious caballeros in the then-popular Zorro stories. In the novel, despite Alessandro’s native heritage, he is very piously Catholic; although the movie’s Father Salvierderra does marry Alessandro and Ramona, we don’t hear Alessandro say anything Catholic and instead presume Ramona has converted to Temecula. After things go horribly wrong, the film’s Ramona prays to Mother Mary saying “Forgive me!” suggesting she’s sorry she suspended her Catholic faith. You’ll forgive me if I read this as one of several somewhat mixed messages from the movie, to wit:

Ramona’s first narrative title card reads “Early California in the colorful days of the Spanish Dons,” as we cut to mission bells, monks in repose, and miners pickaxing a river. At a massive hacienda, we meet Señora Moreno, “owner of the greatest rancho in all California,” who rules with an “iron hand” over “feudal grandeur.” Staunchly severe Moreno enters the kitchen, strides imperiously amongst the noticeably browner women, and asks one of them, Marda, “Have you seen Ramona and my son?” A pigtailed Ramona cheerfully rides a burro on country grounds as a card tells us of the mystery in her dark eyes and her adoption by Señora Moreno. Don Felipe Moreno begrudgingly holds the mule’s tail as a card tells of his proud Castilian blood. Ramona pulls Felipe onto the mule, sees his happiness, playfully pushes him off the mule, sees his anger, prods the mule, and loses the race as Felipe stops the mule who throws Ramona over his head. Felipe puts her on his back for the walk back to the hacienda, where the two of them mischievously sneak around staunchly sour Señora Moreno, who affectionately kisses her son and sends him to wash up for supper, then criticizes Ramona’s tomboyish outfit, manners, and lack of love for her. Ramona flips the question back, asking why Señora Moreno has never shown even an adoptive mother’s love. When the Señora falls asleep at dinner, Felipe gathers a plate of food, sneaks out of the dining room, sneaks into Ramona’s room, gives her dinner, and shares nose-to-nose affection that might be fraternal…or more. After three years at a Los Angeles Convent, Ramona returns to sneak a flower under the nose of a guitar-strumming Felipe, who embraces her and asks her to dance. Ramona’s energetic courtyard dance inspires Marda and a club of her colegas to clap along, but when staunchly surly Señora Moreno arrives, the workers scatter. Ramona finds the fulsomely Franciscan Friar-ish Father Salvierderra in the woods, kneels, kisses his hand, and gets his blessing. At least a dozen Native Americans ride horses across a river until we meet Alessandro, “the captain of the sheep shearers, son of the last chief of the Temecula Indians.” Alessandro quarters his men, greets Señora Moreno, requests and receives Father Salvierderra’s blessing, salutes Don Felipe like an old friend, stops by the river, spies Ramona doing washing, and is smitten. In cuts of people looking offstage right, we see the entire cast singing “the sunrise hymn,” followed by Ramona asking Felipe to explain the mysterious beautiful voice which he identifies as Alessandro’s. Well before any such thing as Disney princesses, we, and Alessandro, see Ramona’s amorous affinity with animals, including birds that ride on her shoulder. As Alessandro’s men shear the sheep, Alessandro sneaks off to leave a small pot of small flowers on Ramona’s barred window, which she places in her un-pig-tailed hair as she accepts his hand-kiss. Weeks later, Felipe ardently reveals to Ramona that he often thinks of their happy childhood, but “You have grown into a beautiful woman – and I would like to tell you…” She interrupts, “Felipe you know I love you – as a brother.” Ramona meets Alessandro at a thick oak, where he reminds her he’ll be leaving tomorrow, declares his love, hears her gladness, and asks, “Señorita, do you mean that you are mine? That you will marry me?” Staunchly sullen Señora Moreno shows up, demands to know why Ramona is dishonoring her, and hears “Señora, we have done nothing wrong. Alessandro and I are going to be married.” Moreno takes Ramona to her private bedroom, locks the door, pulls out a chest of “precious jewels,” and explains “your father gave it to my sister, Ramona, whose name you bear.” Somewhat like Martha in Body and Soul, Moreno promises the young woman the treasure if she marries a man “who is not beneath you,” but if not, the jewels go to the church. Ramona says she’ll give up everything to marry Alessandro, and Señora Moreno slaps her and threatens to return her to the convent. Kneeling, crying, Ramona asks why she can never know who her mother was, and staunchly saturnine Señora Moreno says, “Your mother was an Indian, your father was a white man. He married her after my sister refused him.” Randomly, Ramona rises, raises her arms, roars, berates Señora Moreno, runs out of the room, and relegates Marda and Felipe with, “have you heard? I am an Indian!” While Alessandro waits at the oak, Ramona wraps up all her stuff in a rug, but can’t walk away because Moreno locks her in her room. Felipe opens it and tells Ramona he’ll sing to distract his mother while she gets away. Ramona replies, “Goodbye, dear Felipe, I will love you always,” and kisses his mouth, causing him to take her in his arms and declare his non-platonic love. When she keeps treating him like a brother, he reluctantly blesses her journey, steps out of her room crying, and tearfully sings to his mother, who compliments his beautiful voice. Ramona successfully sneaks past the Morenos to rendezvous with Alessandro, who departs with her on horseback into a “dark, secluded canyon.” Ramona holds Alessandro, declares herself at home for the first time, speaks (according to him) “in the language of our people – the stars – the flowers…,” lies down, and receives a kiss as the film flashes forward to their wedding, officiated by Father Salvierderra. A title card welcomes us to the couple’s home in a village several years later, where Ramona prepares food, looks over their bountiful farm, and shares affection with her husband and toddler. At the hacienda, Marda laments that Felipe hasn’t been the same since Ramona left and his mother died. At the Temecula village, Alessandro arrives with the awful news that the doctor won’t treat their sick son because they’re Indians. Ramona holds her child in her arms as he dies, prays to a statue of Mary, “Holy mother, forgive me,” and screams to hear Alessandro sawing together a miniature coffin. A card says “Marauders motivated by hatred and greed, descend upon the defenseless Indian village,” and we witness a rather impressively filmed scene of swarthy beardy white guys on horseback overrunning the village and iniquitously liquidating the indigenous, seen in forlorn, blood-soaked close-ups. Holding her Mary statue like a baby, Ramona escapes to a distant hill with Alessandro as they weep to watch the whites burning their home to the ground. A card tells us Felipe failed to find Ramona and Alessandro “in all the Indian villages between San Diego and San Francisco.” Father Salvierderra informs Felipe that since the massacre, no one has heard from them, but we see them in the couple’s high mountain cabin. When an exhausted Alessandro returns riding an unfamiliar horse, Ramona warns that he’ll be accused of stealing, but he assures her he only traded their old horse and sends her to the stream for water. Sure enough, a white on horseback turns up, calls Alessandro a thief, and shoots him dead, Ramona arriving just too late to save him. Ramona goes mostly mental, screaming while pushing through scrub brush that cuts open her face, and lying comatose in an “Indian hut” for ten days. Felipe finds her there with blank open eyes, where another Native American tells him she’s not ill, but has lost her memory. The hacienda help happily hails the homecoming of Ramona until they see she’s awake but catatonic. In the courtyard, with the staff watching, Felipe recalls “every happy incident of their youth,” moments we see in flashback. Ramona flutters, flickers, spins, dances, and falls into her step-brother’s arms, saying “are – are you Felipe?” As he answers affirmatively, he appears more than ready to kiss her lips, but she turns her head and says “Why, why, it is just as though I had never been away.” Instead of Jackson’s ending of marrying Felipe, Ramona perhaps more realistically keeps him in the friend zone.

Despite the soapy aspects, Ramona sustains as perhaps the best surviving silent feature directed by a Native American, and as a relatively nuanced look at indigenous-slash-Mexican-slash-white relationships. The white slaughter of the Temecula village is almost better for being less motivated than it is in the book; the imagery remains fierce and uncompromising for any era, especially considering we well-nigh witness the white-caused deaths of two indigenous infants. Also, Ramona was one of a few movies to make Dolores Del Rio into a star, but it was arguably her signature role, an impression abetted by a certain bit of music.

In March 1928, two months before Ramona was to be released, Dolores Del Rio appeared on a radio show along with Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, John Barrymore, and other stars to show they could still star in the sudden new era of sound cinema. Del Rio’s accent was as thick as that of anyone who’d been speaking English as a second language for less than three years, but on the show she wowed listeners by beautifully singing a new song written for the film called “Ramona.” A few days later, Del Rio recorded two studio versions, one in English and one in Spanish, that were used in radio promotions and on a Vitaphone record soundtrack, but neither in the film itself. Accounts differ: some say that United Artists shoehorned part of her recording some versions of the film, but those is lost; others say UA didn’t have time to slip anything in; still others say Carewe looked for an artistic way to use the song but couldn’t find the right spot or perhaps…didn’t want to?

If Edwin Carewe was hoping truth would emulate fiction, he may not have been happy with the results. I told you that indigenous sophisticate Carewe saw similarities in the Helen Hunt Jackson’s story of the indigenous sophisticate Alessandro who came along to sweep this poor little Mexican rich girl off her feet. However, Dolores may have seen Jaime as her Alessandro and Edwin as her Felipe. In mid-1928, Dolores divorced Jaime, killing their relationship as surely as the film’s redneck killed Alessandro. I mentioned the altered ending’s relative friend-zone realism, and Dolores Del Rio arguably emulated that realism with the press after her next film under contract with Carewe and United Artists, Evangeline, when she told reporters, “Mr. Carewe and I are just friends and companions in the art of the cinema. I will not marry Mr. Carewe.” Del Rio didn’t need to add that she was contradicting many rumors that Carewe had planted in the press, but with her under contract, Carewe threatened to make her onscreen life hell, much as he had planned to make his then-current wife’s life hell. Del Rio fought back, canceled her contract, received his lawsuit, and they settled out of court. Carewe’s ramped-up revenge was remake a 1927 hit of Del Rio’s, the Russian-set Resurrection, as a film starring Hollywood’s second-biggest Mexican star, Lupe Velez. The 1931 film did mediocre business, and Carewe directed one more film, ever, in 1934. It’s hard to avoid the impression that Edwin Carewe threw away his career out of frustration for his unrequited love of Dolores Del Rio.

Influenced by: Two previous versions, one directed by D.W. Griffith (!), both of which Carewe improved upon with more authentic indigenous culture; this was UA’s first film with synchronized sound and music, but not dialogue, marking this as a transitional silent

Influenced: suffered from timing, because by 1928 everyone wanted dialogue, but Del Rio proved her chops, partly by singing the theme song, and soon became Hollywood’s biggest Latina star of the 20th century (until Jennifer Lopez)

~

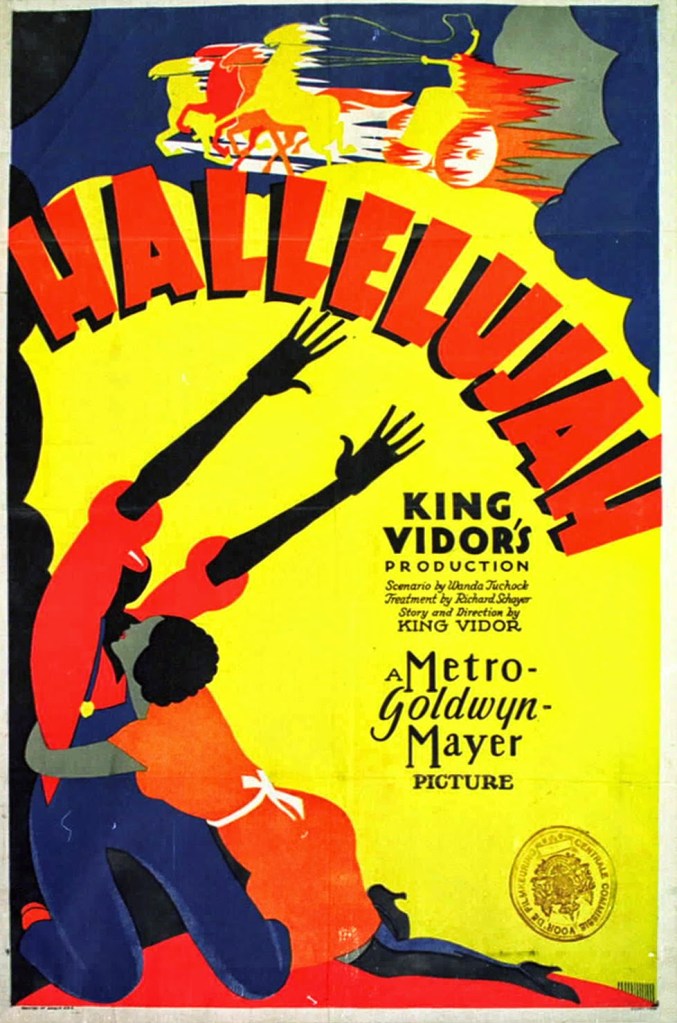

C6. Hallelujah (Vidor, 1929) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Wilson read analysis by Reinhardt listen to my podcast

“Seems like you made it mighty late to get ’round here to be married. The damage is all done!”

By the standards of the 1920s, King Vidor was another ally who also happened to be one of the most powerful and successful directors of the 20s. Vidor said, “For several years, I had nurtured a secret hope. I wanted to make a film about Negroes, using only Negroes in the cast. The sincerity and fervor of their religious expression intrigued me, as did the honest simplicity of their sexual drives.” Despite Vidor’s tremendous track record, MGM resisted until Vidor promised to invest his own salary, dollar for dollar, with that of the studio, whose then-head of production, Nicholas Schenck, reported told Vidor, “If that’s the way you feel about it, I’ll let you make a picture about whores.” It’s not clear if he meant that hypothetically.

Donald Bogle recounts how the Black press, uh, pressed MGM into making crucial hires behind the scenes for Hallelujah. Vidor sought realism by moving parts of production to Tennessee and Arkansas – the distance from L.A. to the Deep South by far the furthest an all-black cast had traveled to make any kind of film – and there they consulted black leaders on “everything from river baptismal services to revival meetings.” The real Curtis Mosby performed while the real Eva Jessye supervised choral sequences, including one that needed 340 black extras who all had to know how to sing. Bogle writes, “That Sunday morning, black church choir benches in the city were said to be practically empty.” Bogle goes on that “though sequences of black crapshooters and rowdy cabaret folks were familiar images, nonetheless the film sometimes attained a highly moving cultural authenticity.”

Hallelujah begins with the MGM lion, but instead of hearing his roar, we hear a mashup of tribal drums and choral vocals taking us through bits of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “Hallelujah,” “Let My People Go,” and “Way Down Upon the Swanee River.” In a cotton field, we meet Zeke happily teasing kids and a woman he calls Mammy as they finish for the day and haul in the cotton singing “Cotton, Cotton.” After the sharecroppers finish their picnic-table dinner that evening, Zeke’s brother Spunk plays banjo while some of the boys tap dance. When one Missy Rose plays an indoor piano for the group, Zeke sneaks in and seeks to sneak a kiss that Missy clearly does not want, and Zeke seeks forgiveness by speaking, “it looks like the devil’s in me here tonight.” In glimpses, we see life on this rural plantation consisting of women hustling after children who say good night in a large room full of single beds. Hearing passing troubadours, Zeke sings “At the End of the Road,” a chorus stops and joins in, and Spunk uses machines to lathe the cottons into bales. We hear another song about what we’re watching, cotton bales getting rolled into a paddle steamer riverboat, as we wander to the payment office, where Zeke collects his plantation’s full cash payment. A nearby woman, Chick, dances high-step jigs in the middle of an appreciative crowd that comes to include Zeke, who tries to pull Chick aside, hears her throw shade that he’s poor, and flashes his money wad. In a surprisingly legit juke joint/dance hall, Chick performs a spunky, spirited “Swanee Shuffle” then settles in to a slow dance with Zeke, who hears Chick tell of how lucky her last beau got with a sucker named Hot Shot whom she just happens to spy. After Hot Shot insults Zeke as a buck-and-a-half cotton-picker, Chick successfully persuades Zeke to shoot dice with Hot Shot…and lose all $100 of the cash he was holding. When Zeke demands to see Hot Shot’s dice, Hot Shot insults him, Zeke pulls a knife, Hot Shot pulls a gun, Zeke fights him for the gun, and Hot Shot just happens to shoot Spunk who just happens to walk in the door. As Zeke holds his dying brother in his arms, we see Hot Shot and Chick hiding in a nearby room arguing over percentages of the take. When Zeke brings home Spunk’s corpse, he prompts all the plantation people to chant, cantillate, cry, and croon, until Zeke’s “pappy” staggers outside, points out the parting of clouds, and inspires Zeke to sing with open outstretched arms of the coming of the Lord. The rest of the plantation joins Pappy on his knees as Zeke gestures heavenward, hails Hallelujah, and segues into a reverent “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” A title card says “And Zekiel became a Preacher,” and a berobed, redubbed Zekiel rides a donkey in an elaborate town parade attended by a poshly dressed Chick and Hot Shot, who push through the paradegoers to heckle Zekiel until Mammy, riding along near Zekiel, says “ah shut up, you yellow hussy…all you want is to get after my boy!” Zekiel stops his donkey, wags his finger at Hot Shot, claims to be an instrument of the Lord, assaults Hot Shot and Chick, and gets back on his donkey. At an outdoor revival meeting, on a raised wooden stage, Zekiel offers some of that old time religion, calling the people “friendly and kind,” on their way to the next station of faith, where they’ll “surely” avoid the devil. Chick joins the crowd to fire off libels and taunts, but most of the crowd ignores her in their elation at the sermon, and by the time Zekiel revives the song “At the end of the road,” Chick is crying to be saved as well. At least 200 believers gather for a river baptism, where their splendid singing is, uh, swamped by wailing from Chick, who gets baptized in the water, falls into Zeke’s arms, cries that she’s sanctified, and tempts Zeke into carrying her into a tent before Zeke rebukes himself better. Back at home with Pappy and Mammy, Zeke asks Missy Rose to help him drive out the devil by marrying him, to which she accepts through tears of…ambivalence. Elsewhere, Chick sings hallelujah to a cracked mirror until Hot Shot turns up, guffaws at her falling for that fake preacher, sees she means it, and grabs her, prompting her to beat him with a poker. Chick sees a second sermon where Zekiel sanctifies, purifies, and saves the sinners with word and song, but Missy Rose and Mammy aren’t happy to see him mesmerized by Chick to the point of following her outside as though ensorcelled. Missy runs into the woods for him, fails to find him, and returns to the enraptured and supportive congregation. Months later, Zeke works at a log mill, walks home, and notices a buggy outside his new shack, as we cut inside the shack to see Chick hold a kiss on Hot Shot, hear Zeke approach, and hustle Hot Shot out the backdoor. When Zeke enters with accusations, Chick takes him outside to show him no buggy, then inside to speak tenderly to him, sit in his lap at the kitchen table, caress him, and assuage his doubts until she’s sure he’s asleep. Chick tiptoes into the bedroom, packs a suitcase, and sneaks out the window, but the suspicious Zeke lifts his head and dashes into the bedroom to see her gone, whereupon he seizes a rifle, jumps out the window, sees her jumping into the buggy with Hot Shot, and fires upon them. Hot Shot and Chick seem to escape, but their speeding buggy hits a rough patch of mud and loses a wheel and Chick, who Zeke catches up with in a mud puddle begging for forgiveness and salvation before she dies. Without a rifle, Zeke chases Hot Shot through a tree-lined swamp, finally catches him, and maybe kills him. We next see Zeke breaking rocks on a chain gang until the title card “Probation,” leading to Zeke strumming a guitar singing “coming home” on a cotton bale on the river and on top of a train. Zeke hides behind a tree and surprises his family, who welcome him back with open arms and Missy Rose’s kisses and promises of chitlins and an invitation to help with the picking. Sharecroppers lug bales of cotton to the plantation over music as the film ends.

Hallelujah has accounted for many academic arguments. For every person who lauds its “freshness and truth” that wouldn’t be seen for 30 more years, another person calls it paternalistic, promoting of stereotypes, and, uh, pretty racist. Pioneering African-American scholar Donald Bogle sent his own mixed messages, praising its cultural authenticity in one book, reviling Chick as the uber-tragic mulatta in another book.

Warner Bros. now owns the film and puts a disclaimer on it that says it: “may reflect some of the prejudices that were common in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These depictions were wrong then and they are wrong today. These films are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed. While the following certainly does not represent Warner Bros.’ opinion in today’s society, these images certainly do accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.”

Film critic Kristin Thompson objects to that warning because it basically labels the film as racist, and for her, “Warner Bros. demeans the work of the filmmakers, including the African-American ones. The actors seem to have been proud of their accomplishment, as well they should be.”

When Melvin Van Peebles died in September 2021, his son Mario, also an accomplished filmmaker, said, “Dad knew that black images matter. If a picture is worth a thousand words, what was a movie worth? We want to be the success we see, thus we need to see ourselves being free. “ I think Hallelujah sometimes shows this, although it’s not consistent. So it’s essential without being sufficient. It at least moved the conversation forward – if this, why not that?

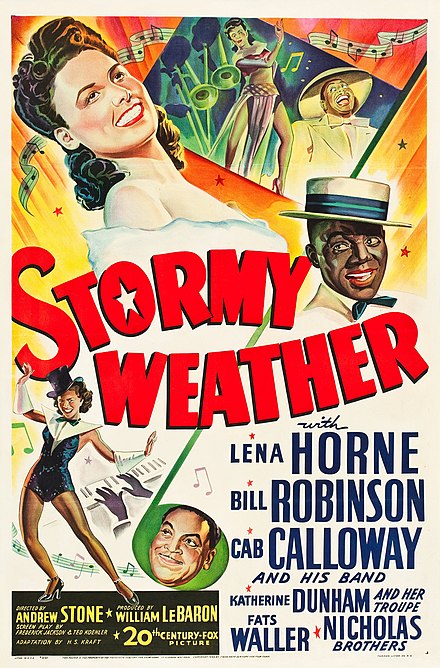

As it turned out, Hearts in Dixie and Hallelujah both did reasonable but not boffo business, their Northern receipts not quite making up for the absence of Southern ones. Hollywood would not attempt another all-black film for…wait for it…wait for it, Black people certainly did…seven years. Of course, Black people were in films, from Stepin Fetchit vehicles to Imitation of Life, which we’ll discuss in a few minutes. But Hearts in Dixie and Hallelujah established the pattern: a white producer would feel strongly about the relative novelty of exploiting black music as part of an all-black cast, a studio would agree but cut corners, the resulting film wouldn’t smash box office records, and white Hollywood would shake its head and use the film as a cautionary tale for any future all-black-cast projects. After 1929, the same thing would happen in 1943, with Cabin in the Sky and Stormy Weather, and then again in the 50s with Carmen Jones and Porgy and Bess, and then in the 70s with The Wiz, and, yes, in 2006 with Dreamgirls.

Influenced by: jazz, Stephen Foster, Vidor’s interest in “negro spirituals,” prevailing racism

Influenced: mainstreaming of both African-American culture and stereotypes, but because it and Hearts of Dixie (also 1929) bombed, 14 years passed until another major studio film with an all-black cast

~

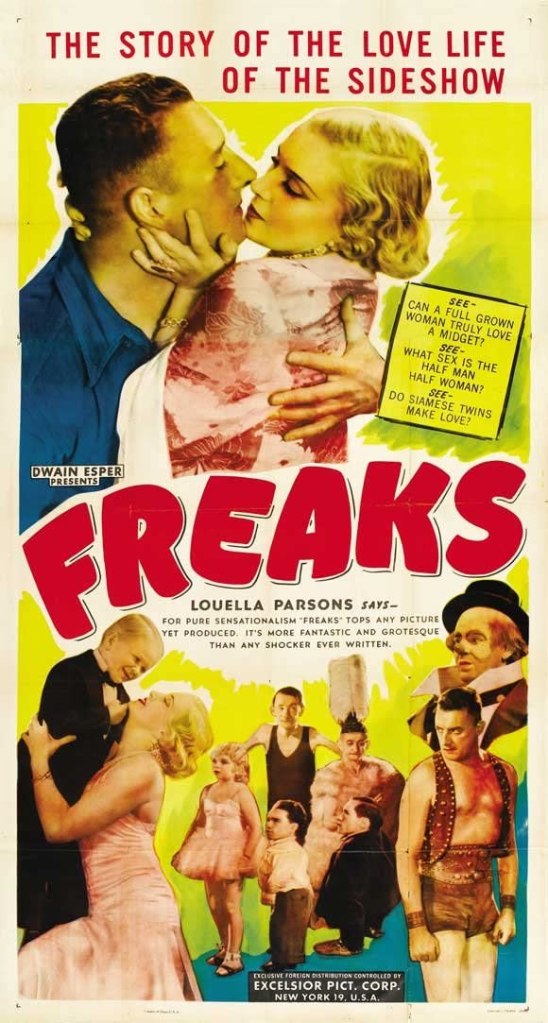

C7. Freaks (Browning, 1932) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Weathers read analysis by Eggert listen to my podcast

“We accept her, we accept you, gooba-gabba, one of us, one of us.”

MGM bought the rights to Tod Robbins’ story “Spurs” back in the silent era, but was spurred to make it by director Tod Browning after the success of Dracula, which spurred Universal to re-orient toward the horror of characters like Frankenstein, the Invisible Man, the Mummy, and maybe a werewolf or phantom or hunchback or whatever Universal might have available. In that context, the idea of a single film about unusually formed circus sideshow performers looked like the more mature take on a trend, exactly the kind of film MGM’s then-director of production Irving Thalberg preferred to make. By then, MGM was trying to become classier, and no longer had Nicholas Schenck vocally approving of pictures about whores, although that didn’t stop the adaptation of Spurs from centralizing a gold-digging woman.

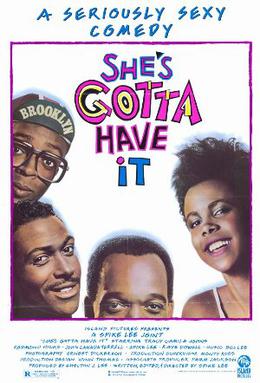

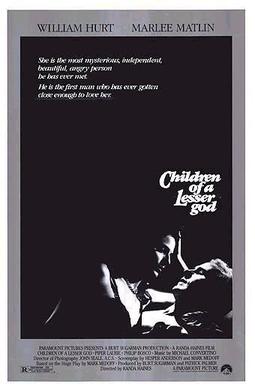

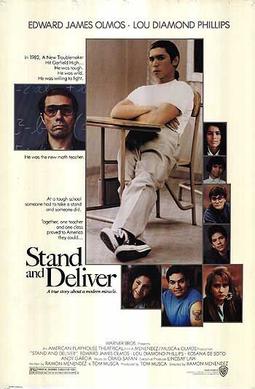

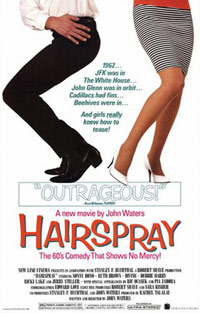

Thalberg was the named producer on Freaks who by all accounts closely collaborated with Browning on every aspect of pre-production, from set design to planning the 24-day shooting schedule to casting. At first, Thalberg wanted to cast stars as the full-size humans, but Thalberg came to agree with Browning that stars would overshadow the film’s real stars, who were the so-called Freaks. That said, Thalberg didn’t trust the foreign accents of the contract players he did cast, and was worried that MGM’s pre-existing carnival set would look too American, so he moved Robbins’ story from France to the U.S. Thalberg also wound up moving some of the principal actors from the MGM commissary to a special tent for their meals, because some MGM stars were disgusted by having to eat next to the sideshow attractions. They had something in common with test audiences from January 1932, who supposedly ran out, became ill, fainted, and/or threatened MGM with lawsuits. Louis B. Mayer was ready and willing to destroy the negatives, but Thalberg fought his boss and supervised an edit that severed 30 minutes of Browning’s 90-minute cut, ironically truncating Freaks into the sort of two-thirds-stature creature that the film was celebrating. (To make sure it ran at least an hour so as to play at proper venues, they had to add the carnival barker frame story and the epilogue.) As was then custom, the removed footage was destroyed.