Who’s ready to dive into the world’s most divine documentaries? The first three seasons, or lists, had an American focus, but I’m now excited to expand the lens to cover the entire world. But we have to start with the elephant in the room: how did I decide on these particular 100 documentaries as history’s most important?

As usual, I didn’t. I just narrowed down other people’s lists. In the case of documentaries, my populist authority was Letterboxd, from which I took all of their Top 25. My elitist authority was the 2012 Sight and Sound poll, from which I took all of their Top 55. And my more general, authority of authorities was Metacritic. With caveats, I managed to include all of Metacritic’s Top 170. You wouldn’t be crazy to ask how I made a list of 100 films from a list of, uh, 170 films. All the major sites, including imdb, Rotten Tomatoes, and many others, suffer from overwhelming recency bias when it comes to documentaries, perhaps because in the algorithm era, critics ranking a strong documentary 100 out of 100 has never been more urgent – or easier. While I agree that technology has improved, I don’t agree with the way major sites agglomerate the critics because the results suggest that more than half of history’s best documentaries were released in the 2010s. In what I consider a very generous compromise to recency bias, I decided my Top 100 documentaries list would consist of no more than 25 films from the 2010s – a quarter.

Five other criteria: 1, no short films, one hour minimum. 2, no TV shows per se, like Nova and Frontline, although movies that debuted on TV are okay. 3, for the sake of my guests, the film has to be available for streaming (paywall or not) on something like Amazon, Apple, Kanopy, HBO, Criterion, or Netflix. Yes, I realize that prejudices against certain great docs that need our help the most, but I’ll be back to get those films on the N-list – the non-fiction 100. Rule 4, no more than two films made by any particular director – their third-best film will just have to wait for that N-list. And finally, 5, based on my decades of reading scholarship and a bit of curator discretion, I squeezed in ten films that somehow missed the best-of lists but are historically crucial, e.g. Fahrenheit 9/11 and An Inconvenient Truth. (Had I not squeezed in Why We Fight: Prelude to War and instead relied entirely on the critics, there would have been NO films between 1938 and 1956.).

~

D1. The Battle of the Somme (Jury, 1916) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by IWM read analysis by Clouting listen to my podcast

“Industrious French peasants continue their activities just outside the firing line. Care of artillery horses. The mascot of the royal artillery field caught in France.”

There are two conventional ways of beginning the history of documentaries. One is to start with the very first theatrically presented films, made by the Lumiere Brothers in the 1890s and well known to every real cinephile. Because of this list’s criteria about feature-length films, I leave the Lumieres and Dickson and the rest to another list. The second traditional method of beginning the history of documentaries is to start with Nanook of the North; if you google the words “first documentary feature” you will see plenty of Nanook. As a film historian, my problem with that is that there were popular documentary features before Nanook. No, they weren’t called documentaries, and no particular one had quite the sureness of form, or influence, of Nanook of the North. No doubt, Nanook deserves its place early on in this list, but I also wanted to complicate that picture just a bit, to remind my digital museum’s visitors that Nanook’s director, Robert Flaherty, didn’t exactly invent everything.

Several popular feature documentaries were made before 1922, although not so many as to merit more than one place on this list. After a good deal of consideration, I settled on The Battle of the Somme.

By summer of 1916, after nearly two years of war, many Western citizens had become accustomed to viewing short newsreels about the calamitous conflict. In a time before television and indeed before radio for most people, nickelodeon newsreels made the carnage unprecedentedly visual and vivid. The antecedents for filmmaking the film called The Battle of the Somme were related to the antecedents for warmaking the conflict called the Battle of the Somme. In 1913, few Britons could have told you where the Somme was; two years later, most knew it as the notorious “front,” the deadly demarcation between Allies and Axis powers. In that year of 1915, the Allies privately agreed that sometime during the following summer, the Somme would see something like an all-out assault from the allies. The world’s first extensive trench warfare had mostly resulted in a frustrating stalemate, and Britain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands steadied themselves for an attack unlike anything the world had ever seen, an offensive of hundreds of thousands of troops directly into German-occupied territory.

As journalists and filmmakers followed the troops collecting near the front, the phrase “the battle of the Somme” elevated from whisper to sotto voce. The British Topical Committee for War Films sent several cameramen; Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell wound up leading the teams starting with movements and preparatory artillery bombardment on June 26, 1916. Within two weeks, Malins and McDowell shot about 8000 feet of celluloid. Sometime around Bastille Day, the War Films’ office’s lead editor, Charles Urban, suggested that the footage be formed into a full feature instead of the usual short newsreels. At that point, D.W. Griffith’s three-hour anti-war epic The Birth of a Nation had been playing to packed British audiences for almost a year, expanding possibilities for “reelers” and attention spans. While Griffith was trying to set his version of the past into amber, the British Topical Committee was trying something new, a feature that would play like a live feed, a 77-minute film titled “The Battle of the Somme” that would play in theaters while that very same battle was raging.

The Battle of the Somme begins with a title saying “Preparatory Action June 25th to 30th Showing the Activities Before Fricourt-Mametz,” while assuring us this was representative of much of the British Front. We see many disassociated troops, horses, and cannons at a muddy intersection. A title card tells of a general addressing fusiliers, followed by the visual of an officer on horseback delivering an address surrounded by orderly soldiers standing in a circle. A title card praises munitions workers for making shells just before showing the so-called “dump” of munitions shells by a 1916 version of a truck; we see a massive pile of hundreds of arm-sized shells passed along as a fire brigade would do. As platoons march in formation, most soldiers cheerfully look at, acknowledge, or even wave to the camera. Cannons are prepared and fired between shots of troops marching and other troops munching. Title cards tell us that the larger-shell “flying pigs” killed “two dumb victims” whom we see – the corpses of two unfortunate horses. A title card heralds the morning of the attack, July 1st 1916, and cuts to firing cannons giving way to many men standing around laughing, followed by an officer hustling soldiers into a trench. A title card braces us for a no-man’s land whose subjects endured heavy machine gun fire 20 minutes after the next shot, causing us to wonder how many of the dozen enlistees looking at us were giving some of their last looks. The front of the front isn’t quite we expect from narrative cinema; instead, we see walls of sandbags without another wall to make a trench. The film presents many ragged open fields, a few explosions, a lot of scrambling, and a card that tells us the following soldier died 30 minutes after being filmed. During the next sequence, many wounded men are carried on stretchers as the bearers still tend to smile at the camera. Horses drag wagons of artilleries; battalions march over hill and dale. In one extreme long shot from atop a hill, we and soldiers look to the distant horizon where at least twenty different smoke flumes indicate a fiercely contested battle. A doctor examines a wounded man near a half-dozen men on stretchers to show, according to a card, how quickly the wounded are attended. More wounded are walked into the front accompanied by the title cards’ descriptions of “Tommy” kindness to captured Germans. A card declares soldiers assembling for roll call, possibly meant to ironically describe the many soldiers pictured resting. The next sequences might as well have been titled “at ease,” mostly groups of soldiers relaxing or polishing arms between assignments. One final marching battalion cheerfully tips their helmets to the camera just before the film cuts to a map and ends.

On August 10, 1916, The Battle of the Somme, the film, premiered for royalty. On August 17, a recommended musical medley for the film by J. Morton Hutcheson was published in the newspapers. On August 21, the 77-minute film went into general release, where it enjoyed “unprecedented” popularity, likely viewed by as many as 20 million Britons during August and September while the actual battle of the Somme was very actively happening. In an effort to guide the film’s many viewers who had never seen a film, critics warned about the depicted violence even while contextualizing it as a difficult moral necessity. One review praised its recruiting power, calling it “a powerful spur to national effort”; another review said if the film’s exhibition “does not end War, God help civilization.” Thus began debates over war-based feature documentaries’ propagandistic value in continuing or ending wars.

More than 100 years later, we’re still arguing about this. This was probably the first documentary feature film whose audience could be measured in the tens of millions; this was one of the first films to demonstrate the range and power of feature-length propaganda.

Influenced by: a lot of wartime “actualities” (not yet called documentaries)

Influenced: films like this set the standard for “actualities” until Robert Flaherty came along

~

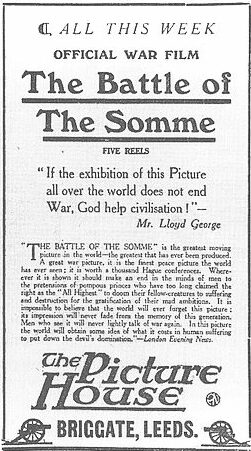

D2. Nanook of the North (Flaherty, 1922) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on criterion watch analysis by Rud read analysis by Zimmerman and Ayuash listen to my podcast

“As soon as I showed them some of the first results, Nanook and his crowd were completely won over.”

It is now time to also acknowledge the influence of a century’s worth of historiography that established the list’s next film as the most popular silent documentary and the first well-known ethnography, blazing a trail that led to, among other things, most of National Geographic’s filmic content.

All this began with a man born in 1884 in Michigan to an iron ore prospector who eventually sent him looking for minerals in Canada’s Hudson Bay. In 1913, Mister Robert Flaherty took Eastman/Kodak’s new class on movie camera operation to do his job better, but when he returned to Hudson Bay he found himself more interested in filming the local Inuits, or as whites then called them, Eskimos. Flaherty spent the better part of the next three years filming Inuits. He edited it into a film, showed it to enthusiastic friends, dropped his own cigarette on the original negative, and lost all of it, something Flaherty would later credit for saving the world from a boring travelogue-like film.

With America and the world at war, Flaherty found difficulty fundraising to re-film his, uh, Eskimo adventure. One film that both helped and hurt him was Edwin Curtis’s In the Land of the Head Hunters, from 1914. Although I considered putting Curtis’s unusual docudrama on this list, three things worked against its inclusion here: it was a spectacular failure at the box office, its title is racist and misleading, and it’s arguably not documentary considering how much of it is scripted and staged. To be clear, as I’ll discuss at some length, every single documentary contains scripted and staged scenes. Nonetheless, In the Land of the Head Hunters, which is both the first feature made with an all-indigenous cast and the oldest surviving feature made in Canada, is an unacknowledged stylistic antecedent to Nanook, as well as a financial failure that Flaherty saw as a cautionary tale.

Flaherty spent much of the second half of the 1910s trying to convince someone to let him remake his Eskimo film as something more focused on one family, and eventually, by 1920, Flaherty convinced top French fur company Revillon Freres to fund the film. Over the next two summers and winters, Flaherty allied himself with the First Nations (as Canada now calls them) to stage scenes and re-enact events that he didn’t capture quite so well the first time. He put the focus not only on one family but on one charismatic warrior, Allakariallak, who apparently named himself Nanook for the sake of unsophisticated white tongues.

In the film’s current opening titles, Flaherty spends maybe too much time explaining how inspired he had been between 1910 and 1916 – as though the Inuits have changed a lot since then. He also apologizes that Nanook wanted him to remain another year – and then tells us that Nanook went searching for deer in the woods and starved to death. The film more formally begins with a card saying “The mysterious Barren Lands – desolate, boulder-strewn, wind-swept – illimitable spaces which top the world.” Cards praise “Eskimos” as patient, kind, happy-go-lucky, and the only race who could survive eating no more than the animals they hunt on the east side of Hudson Bay, in Ungaya, an area about the size of England that is home to 300 people. As he parks his kayak, we meet Nanook, the Bear, as well as his wife Nyla, “the smiling one,” and some kids and a husky. We watch Inuits burning moss to hollow out seal skins, draping skins over the kayak, carrying it to the river, and piloting it to a white man’s trading post, where Nanook and family trade bear and fox pelts for knives and candy. Human babies pose with husky babies, Inuit children eat wafers and alcohol, and the white trader shows a gramophone, or phonograph, to Nanook, who bites at the vinyl record. Nanook embarks on a village-saving hunt that includes graphically successful ice-fishing with a spear. Soon, we see a large group of warriors attacking a larger group of walruses, who back-and-forth with the men until one beast is harpooned, contested by its mates, and finally hauled to shore, where the hungry men cut up and devour the walrus parts. Winter falls in the form of human-high snowdrifts, which seems sad and intimidating as Inuits push a sled up a hill…but less sad when they cheerfully ride it down. Nanook finds and kills a white fox that he pulls out of a hole as if by magic. Titles tell us, then visuals show us, that Nanook licks his knife to make it ice over before he cuts ice to build his itinerant family an igloo. While the children sled down the ice, Nanook and friends work the ice into an igloo, culminating in the movie’s money shot: Nanook carving out a microwave-sized ice block window, popping it off, smiling widely, and crawling out through it. Nanook walks over to a diaphanous section the ice, carves out a window, and firmly sets it into the microwave-size gap where Nyla wipes off its frost. Inside the igloo, the family compiles its inventory; outside, one young child adorably tries to fire a small arrow from a small bow. We watch the way Nanook’s family boils seal oil to heat up seal meat in a hearthstone set outside the igloo so that the home walls don’t melt. We see the family sleeping cuddled together. Nyla chews Nanook’s boots to soften them, bathes a babe with a lot of wiping, and kisses him by touching noses. We learn that, at night, igloos keep puppies and kayaks safe from ravenous full-size dogs. For a long time, Nanook plays tug-of-war with a hooked seal who is beneath the ice…until four other family members show up and help pull up the line and the large dead seal. The forlorn, tied-up huskies can only observe as humans scarf down half of the seal, but eventually the Inuits give the dogs some meat which they ruthlessly fight over, causing what a card calls a “dangerous delay.” Nanook and his family charge across a rather wind-swept, mist-covered ice floe until they finally find another igloo, and this time the dogs’ exile outside at first seems deserved…until they seem to endure the worst night of anyone’s lives. After a closeup shot of Nanook sleeping, we see the card “The End.”

Unlike most of the documentaries on this Top 100 list, Nanook of the North does not suffer from inattention, but instead, many articles and even books. How to summarize? In the Library of Congress’s official essay on the film, Patricia Zimmerman and Sean Auyush present Jay Ruby’s argument that Flaherty’s film must be understood in context as well as Fatimah Tobing Rony’s counterargument that the Inuits are presented as “cuddly primitive” and that the film’s mode is less ethnographic than taxidermic, i.e. seeking “to make that which is dead look like it is still living.” The American Film Institute’s official entry peddles in gossip about what the onscreen women were doing offscreen with both Flaherty and Nanook (whose real name was Allakariallak). More significant is the fact that Nanook’s death, shortly after the film’s release, and the ongoing displacement of the film’s subjects were probably both catalyzed by the film’s popularity.

Nanook of the North became a sensation upon its 1922 release and throughout the 1920s, establishing a sort of Eskimo chic evidenced everywhere from pop songs to children’s books (“I” would now be for igloo, “k” for kayak). Nanook’s influence could be felt even in fiction film, but that influence was more profound over the nascent field of non-fiction; afterward, every would-be documentarian had an example to serve as a, ahem, “North Star”. Nanook cast a shadow as long as that of an Arctic sunrise. Anyone approaching the subject of documentary should see it, try to enjoy it (in many ways, that’s not hard), and then think about it. Ah, if only Nanook hadn’t been so staged and paternalistic.

Influenced by: some Orientalism; In the Land of the Head Hunters; Flaherty said “one often has to distort a thing in order to capture its true spirit”

Influenced: cannot be overstated – became known as the first documentary and the first ethnographic film (though it was neither), and validated slippage between fact and fiction

~

D3. Moana (Flaherty, 1926) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Safune read analysis by Rosenbaum listen to my podcast

“Among the islands of Polynesia there is one where the people still retain the spirit and nobility of their great race.”

If Nanook had failed, Flaherty might have gone looking for a job with National Geographic or a similar organization; as it was, in early 1923, Jesse Lasky (of Famous Players-Lasky) signed him and assigned him a sizable budget to make the next Nanook. Having spent years in frozen Canadian tundra, for some reason, Flaherty chose to make his next film a lot closer to the equator. After more than a year in the Polynesian island of Samoa, after Lasky and Paramount sent letters asking for footage, Flaherty repeatedly replied that he couldn’t film anything yet because he was still earning the trust of the locals. He elided his concern that he didn’t really have a story and that the Samoans didn’t have to struggle against nature as much as the Inuits. Finally, he decided to structure the film around a boy’s initiation into manhood, eventually naming the film after that boy, Moana, a word that translates to “deep water.”

As with Nanook, Flaherty encouraged his subjects to revive pre-modern practices – to dress and behave as their ancestors had, instead of in the then-current clothing and customs assimilated from colonialists and other change agents. Once again, a paternalistic Flaherty staged and restaged supposedly spontaneous situations. If you’re hoping that Flaherty might have received some kind of karmic payback, well: he used a local cave to develop the rushes, where the silver nitrate spilled into the water, found its way into traces of Flaherty’s drinking water, and almost killed the filmmaker. However, Flaherty did survive that, 20 months in Samoa, and another year editing back in California, releasing the film in early 1926.

The opening credits present the full title Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age. The two credited director/producers are Robert Flaherty and his wife, Frances Hubbard Flaherty, here finally properly acknowledged. An opening card states, “Among the islands of Polynesia there is one where the people still retain the spirit and nobility of their great race. This is the Samoan island of Savaii. In one of its villages the authors lived for two years, and the generosity, the hospitality, and kindliness of its people made possible this drama of their lives.” The cards also single out Fialelei as interpreter and sympathist who brought forth her people’s “confidence and cooperation.” We watch what the titles tell us is Fa’angase, “the highest maiden of the village,” bundling leaves. A few other Polynesians gather food, including young man Moana, who strips taro root to make bread and cuts down a vine that can and does proffer a friend fresh water. A long line of Samoans bear food and resources through jungle fields to their village, presented to us through postcard-worthy extreme longshots of seaside palms. Back in the jungle, Moana and his fellow hunters cut bamboo and vines into a trap that ensnares a boar, whom the titles call “the jungle’s one dangerous animal.” The boar strikes back against the Safune hunters until they tie the boar’s legs to a long, thick bamboo pole that two bear back to the village. After Samoans venture out on canoe, we watch a rather long medium shot of two of them free diving in clear water until one does spear a fish. A woman gathering food at the shoreline brings up a head-sized clam and puts it, and herself, into the hunters’ kayak. Mother Tu’ungaita makes a dress, called a lavalava, by stripping and smoothing and interlacing mulberry tree bark with some coconut water. We watch a boy, P’ea, climb a palm that towers over other palms, at least 40 feet high, from where P’ea drops coconuts down to Moana who smiles at him from the beach. We witness blowholes, towering waves, a rainbow, and other signs of the South Seas. In closeup shots, we watch P’ea light a fire, trap a crab, and tell the crab he won’t bother his coconut trees no more. In a scene that may amaze modern Hawaiian snorkelers, young Samoans work hard to drown a sea turtle, whose corpse they transport, display, and break apart into jewelry. We watch food prep of breadfruit, taro, and green bananas. Moana practices dances with a woman in a grass hut. We watch a tattoo applied to Moana’s back, punctuated by a title that reminds us that the practice preserves the dignity of his race. Titles continue by telling a witch to drive out evil spirits, and we see…something like that? Another title assures us “Manhood shall be won through pain” as we see weeks’ worth of tattooing on Moana intercut with a choreographed assembly of dancers. We watch kava prepared, offered to elders, and poured over Moana’s tattoos as he has now transitioned into manhood. The choreographed dancers become more elaborate and celebratory.

Released in 1926, Moana was not a hit in the United States, a fact some blamed on the absence of a character as compelling as Nanook. However, that hardly explains why the film did so well in Europe. Perhaps Americans felt literally closer to what they called Eskimos; for movie-going Europeans, perhaps Polynesians and Inuits were more equally exotic and interesting. Another possibility is that religious censors learned of a film with bare-breasted females and managed to keep it out of many American theaters; Europe had no such powerful censorious religious groups. Moana inspired later-legendary British non-fiction filmmaker John Grierson to coin the term “documentary.” Perhaps aspects of it eventually inspired the 2016 Disney film Moana; what can the old silent film say except you’re welcome?

Influenced by: Flaherty’s success on Nanook

Influenced: documentary as a concept; ethnographic films; National Geographic; first ethnographic feature made outside Canada; first film made in panchromatic B&W film; this also became known as the first “docu-fiction” film

~

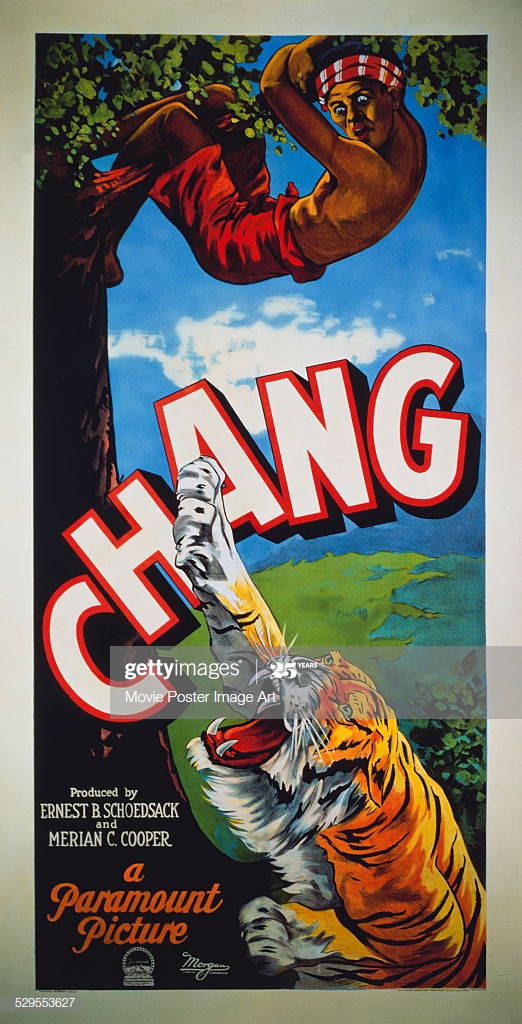

D4. Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness (Cooper, Schoedsack, 1927) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Schoedsack read analysis by Slattery listen to my podcast

“Man, the intruder, came into the jungle…He fought it…He never vanquished it…For strong is the jungle.”

The film’s two American directors, Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack, met in Vienna shortly after the Great War, and established themselves as cameramen for hire to the point of being hired by an explorer named Edward Salisbury who brought them to Malaysia looking for a race of men with tails. Well, they failed to find that footage, but they did leverage that job into another gig in Ethiopia, filming Haile Selassie’s indigenous revolution, and then another job in Persia’s Zagros Mountains filming a nomadic Bakhtiari migration for food for their animals. The latter’s result was edited back home in the U.S., sold to Jesse Lasky while he was waiting for Flaherty to finish Moana, re-edited by Lasky with a new prologue and outtakes, titled Grass, and distributed by Lasky into a minor hit in a few select theaters in 1925. After, Cooper and Schoedsack pitched Lasky on a Flaherty-esque man-versus-nature docudrama set in the only place they knew to be home to bears, leopards, tigers and elephants, in the jungles of Laotian Siam. Lasky loved the idea but not their proposed budget, and they settled on roughly $75,000 to make their motion picture.

Now, does their film belong on a list of documentaries? Context is everything. The word “documentary” hadn’t even yet been coined by John Grierson. Chang is certainly saturated in realism compared to other 1920s representations of Asia, which feature white people in yellowface and Chinese restaurant-style kitsch. Perhaps most importantly, Chang moved the field of documentary forward after Flaherty had more or less founded it.

With Flaherty as role model, Cooper and Schoedsack spent more than a year in the Lao Province of Nan in a house they ordered built far from any other villagers, as Lao would never naturally do. The artifice continued through close-action encounters with tigers and elephants; Cooper wrote to his old boss at the American Geographic Society “Under the instructions of our head office, we are ‘working in’ a slight dramatic theme. The result will unquestionably be quite artificial; yet in its way, it will tell―even if caractitured ―the very real struggle of the jungle man.”

Lasky even hired renowned pulp writer Achmed Abdullah to provide suitably dramatic intertitles. As with Nanook and Moana, the point wasn’t documenting life per se but the excitement that only something looking like real life could provide.

Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness begins with a title card saying: “The Cast: Natives of the Wild: who have never seen a motion picture. Wild Beasts: who have never had to fear a modern rifle. The Jungle.” Abdullah is probably responsible for title rhetoric like “Time and again fields, towns, great Empires were hacked out of the jungle…they are forgotten…always the Jungle rose in its wrath and swallowed them. But man must live…so man fights on.” We meet “Lao tribesman” Kru successfully chopping down a tree that has a meter-wide trunk. We are introduced to his wife, kids, house on stilts, and kept animals like a water buffalo, goats, and a rascally white langur monkey named Bimbo. After a leopard leaps into their goat pen, Kru builds a higher wall and a low trap for the leopard. Kru’s kid gathers a litter of puppies into a basket that he takes into their raised dwelling so that the pups won’t become tiger food; Kru pulls up the ladder and closes a gate. At night, bears frolic, a tiger attacks a stray water buffalo, and that leopard gets ensnared in Kru’s trap. Editing gives the impression that Bimbo the monkey hears the leopard and leads the kids to the trap in the morning, where Kru climbs a ladder and shoots the leopard dead. In the village, locals discuss animal encroachment and make elaborate booby traps. Tree-swinging monkeys observe as one leopard gets ensnared by a rope and another attacks a scarecrow that causes him to fall into a covered pit. Kru uses another trap to kill a tiger and shows us the cat’s fearsome teeth. Kru’s kid moves various small animals around his house’s baskets. Kru hangs a lattice platelet that titles call a mantra, only for those same cards to gloat that the mantra failed and Kru’s rice was ruined the day before the harvest. Kru builds a pitfall large enough for the biggest Chang, a word the titles leave mysteriously untranslated. As hunters in a shallow stream taunt and kill an alligator-sized monitor lizard, Kru comes to ask them for their help in pulling the Chang out of the pitfall, and as we watch them, the Chang is very slowly revealed to be…a child elephant no more than four feet high whom they bind and bring to the village as a beast of burden. At the approach of the mother Chang, Kru’s family flees their raised residence which the mother, ahem, razes to the ground in an apparent rendering of revenge. Bimbo, left alone, scrambles through the forest apparently pursued by a leopard, leading the likewise scrambling Kru to turn, shoot one leopard dead, trap another in Chang’s pitfall, and take a canoe, with Bimbo, to safety as the film cuts to an apparently interested, hungry tiger. In the morning, after his family has arrived in the village, Kru tells them of Chang tracks signifying the return of a crop-destroying Great Herd of elephants. In classic fictional style, an elder scorns the notion with words like “there’s no way there could be…” when he double-takes to see a great herd of at least three dozen elephants who trample through the village, razing all its raised houses. The villagers get busy cutting large trees into big logs into a krall, which is revealed to be a rather massive cage that almost resembles a colonial fort. The villagers use fire-beaters to drive the Great Herd into a shallow lake on the way to the krall, where the “chosen twenty” warriors stand on the parapets and stick the elephants with spears. Older elephants are reported to be easily tamed after weeks in captivity, and sure enough we see Kru riding one of them, his “new slave,” as the beast helps him knock down a tree. Cards say that neither the jungle nor man is ever entirely victorious, but that Kru will “hack” at a renewed non-village life anyway. Bimbo and the kids play happily just before the titles remind us that the jungle is “unconquered” and “unconquerable.”

Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness was nominated for Best Artistic/Unique Picture at the first Academy Awards. Outfitted by Jesse Lasky with a snappy soundtrack, Chang became the first successful sound film of its kind…but what kind was that, exactly? Such films were promoted as real-life adventure or sometimes ethnography or travelogue. Most of them did not flaunt the boundaries of fiction quite as flamboyantly as Chang. Cooper and Schoedsack, for their part, became less interested in so-called “real life adventure” and moved to adopt the novel the Four Feathers and then use their jungle expertise to make the game-changing 1933 film King Kong. But Chang remained a paradigm of a certain kind of non-fiction filmmaking that found its descendants with Steve Irwin and a lot of what is now called reality TV.

This film proved Flaherty’s template could be successfully deployed by other filmmakers and thus broadened the range and dimensions of cinematic ethnography, a practice that can be useful, illuminating and culture-preserving but can also be patronizing and prejudiced (and is known for staging and re-staging “real” scenes)

Influenced by: Flaherty’s success on Nanook and Moana

Influenced: views of Siam and Southeast Asia; these two directors became leaders of ethnographic films until they turned that knowledge to fiction with a rather influential movie called King Kong (1933)

~

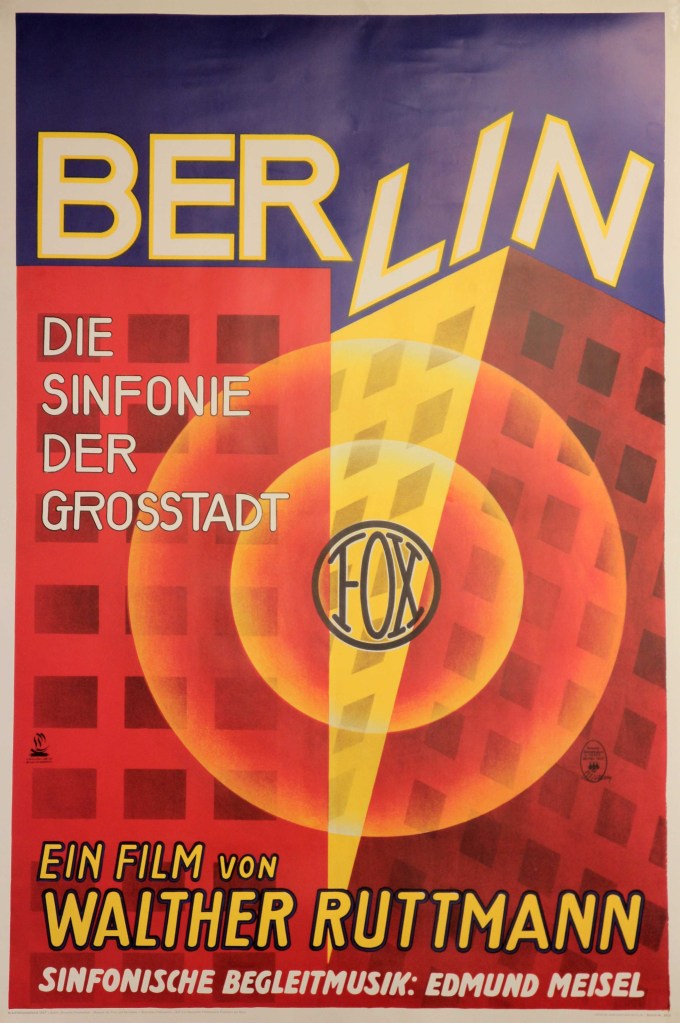

D5. Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (Ruttman, 1927) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Davis read analysis by Thomas listen to my podcast

“Hermanntietz: Grosse Bekleidungs-Woche”

Berlin: Symphony of a Great City can be understood as a confluence or combination of many cinematic trends of the 1920s. One of these was simply the artistic ferment of UFA and Germany during the Weimar period, often studied by first-year film students through films like the Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, and/or Metropolis. Experimentation was generally supported and encouraged, the abstract cartoons of Walter Ruttmann in the early 20s before Ruttmann went on to help Lotte Reiniger make the world’s first animated feature in 1926. By that time, several so-called city films had been made, shorts about places like New York City, Paris, and Moscow, the latter directed by Dziga Vertov, who was supported by Russia’s own experiment-friendly climate at least before Stalin asserted power in the Kremlin. Ruttmann saw these and worked with the Expressionist master Carls, namely Carl Mayer and Karl Freund, to create a film that would weave real-life shots into something like the throbbing pulse of the city, something that everyone began calling a “symphony.” On the brink of the sound era, Ruttmann, Mayer and Freund transformed the nascent “city film” genre into the “city symphony” genre, something that did not escape Vertov’s notice. “City symphony films” were a mini-genre that emerged in the 1920s trying to show, without use of titles or traditional story tropes, the greatness of certain cities;

Berlin: Symphony of a Great City begins with abstractions of water and shapes before landing us on a fast-moving train that whizzes by a sign saying “Berlin 15 km” as it moves steadily past rural trees and phone wires on its way to more suburban and industrial landscapes before landing in, as the railroad station sign says in darkness, Berlin. After aerial shots of the large buildings, we see several dawn-lit, dew-wet, deserted streets until finally seeing a few isolated early-morning walkers, like policemen and poster-appliers. A Potsdam-bound train rolls out of a round switch-rail station as the sidewalks begin to fill up with what look like workers of many shapes, sizes, stations, and sexes. Several board trains, and the trains segue into more industrial vignettes of bread and milk and other essentials being rolled off assembly lines. Kids stop and go on their way to school. A man atop a horse oddly emerges from an urban building, justifying the cut to several men riding horses in a forested glen. Back in the city, the next few minutes emphasize transport options, from trolleys to buses to horse-drawn carriages full of random materials. Popping elevators give way to popping desk doors (back when those existed) to take us to an office of keyboards and phone cables and shouting phone operators who are unflatteringly juxtaposed with howling monkeys and fighting dogs. As the next act begins, trains take us into shallow mines where men and cranes unearth eddies of earth, but the film soon returns to urban Berlin, which mostly consists of people and streetcars walking this way and that. A few curiosos cross our path, like two men quarreling with slaps, a bride and groom emerging from a cab, a recumbent horse slapped back into standing, a funeral, and royalty departing a palace with attendant pomp and ceremony. Planes, trains, trolleys, autos, and horse-buggies dither from hither to thither. Sometimes dolls or other store-window tchotchkes are seen almost nodding in unison; we also see a double-exposure-filled montage of newspapers. After a new act begins with a clock showing high noon, we see the lunch rituals of hardhats, plutocrats, kitchen workers, horses, an alley cat, and various zoo animals. A machine steam-heats dishes and places them back on a rack for new diners while specialists drag a river. Printing presses pump out papers which get wrapped and delivered to citizens as the camera focuses on a few choice words that set off certain sections of the news. The heady view from the front of a roller coaster barreling down its windy wooden track is juxtaposed with a woman, and then a crowd, staring into a river as if someone there has just drowned – though we never see such a person in water. Instead, after a few more anodyne minutes, rain falls, umbrellas pop out, cars drive down slickened streets, and…we find ourselves at a beachfront where scores of kids happily splash. That segues into all kinds of (sunlit) sporting activities, for example dozens of tank-top-toting Teutons running only to be intercut with a hundred pigeons getting sprung from cages. Shadows lengthen as people walk home from work, make up their faces, and lean into their lovers on twilit benches. The new act begins at night as the hoipolloi hit the town. In one particular live theater, we get a long look at long-legged dancers and other circus-ish performers. Some kind of inner ice arena features a fierce hockey match and skiers on a small ski jump. Elsewhere, a boxing ring plays host to boxers – and then, ballroom dancers? The Novelty Club Orchestra brings us into a posher throng of moshers Charlestoning the night away. But the film remembers the working class, both fixing the columns under the posh club and also making merry in a more modest pub. A casino roulette wheel spins into a street scene that spins into circular combustibles that spin into firework bursts that finish with a radio tower over the city as the film finishes.

I find it helpful to remember that no one had yet coined the term “documentary.” They weren’t trying to add a chapter to an expanding documentary field. They were trying to make art out of real-life, without asking the real-life subjects to move in any certain way (that we know of). I do appreciate this attempt toward an aesthetic of urban energy. I wonder if, in 1927, anyone ever got to see this on a double bill with Sunrise, another film Carl Meyer co-wrote, that one directed by F.W. Murnau as his first foray into American filmmaking, because one perspective on urban life is 180 degrees from the other: while Sunrise equates urbanity with vice, Berlin Symphony equates urbanity with something like virtue. Maybe Metropolis is about both, I’m not sure.

In later years, this film would be remarkable for celebrating modern Berlin just before Goebbels made that mandatory. In still later years, after Goebbels and Hitler overreached and Berlin was fire-bombed by the allies, this film would be remarkable for preserving on film buildings that would never be rebuilt, like the Hotel Excelsior, once Europe’s largest hotel.

Influenced by: other city films; Ruttman’s work in abstract (or “absolute”) cinema, although this is considered less abstract

Influenced: impressions of Berlin before, during, and after the Nazis; Man with a Movie Camera

~

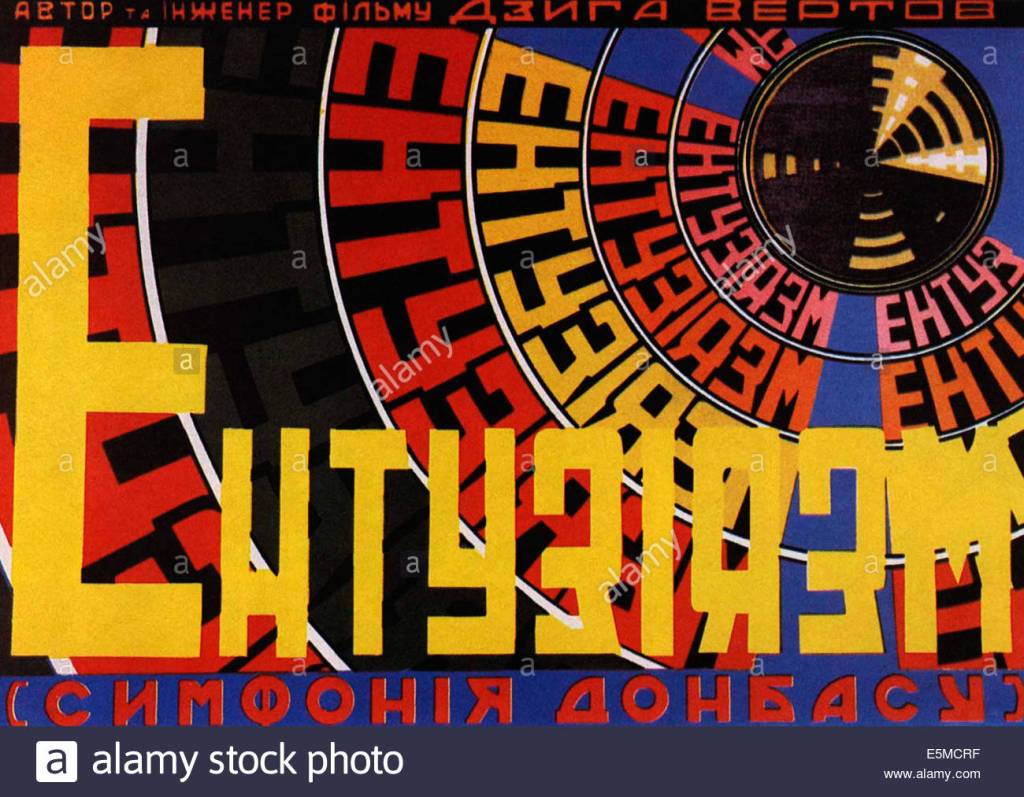

D6. Man With a Movie Camera (Vertov, 1929) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by 100Years read analysis by Michelson listen to my podcast

“This experimental work aims at creating a truly international language of cinema based on its absolute separation from the language of theater and literature.”

Man with the Movie Camera was influenced by the political situation in the recently dubbed Soviet Union in 1927 and 1928. To vastly over-summarize, the Stalinist nationalists were fighting, sometimes openly, with the Trotskyite Communists for the future: would the USSR prioritize its own industrial production or continue trying to foment Communist revolution around the world? After many, uh, twists and turns, Stalin won and exiled Trotsky from the country during the same winter of 1929 when The Man with the Movie Camera was released. The point is that while Vertov may have wanted to make art a la Ruttman, he was more concerned with making something that wouldn’t run afoul of either Trotsky or Stalin…especially the latter, since Stalin was probably going to be soon controlling the means of production including film production.

Listening to Vertov explain this film, or really any of his films, can offer as much shade as light, because of Vertov’s goal of lifting cinema into the same discussions as paintings and sculpture. For example, Vertov writes, “The Cine-Eye plunges into the seething chaos of life to find life itself. The response to an assigned theme. To find the resultant force amongst the million phenomena related to a given theme.” After explaining his wife Elizabeth Svilova’s editing style, sort of, Vertov concludes “As the final result of all this blending, shifts and cancellations we achieve a visual equation or visual formula.” Author Graham Roberts seizes on the last five words of this quote and the fact that even Vertov can’t decide between “equation” or “formula,” with Roberts deciding that “Vertov’s cinematic language has become so rich that it can only be understood in cinematic terms.” Well in that case…

Man with the Movie Camera begins with many titles about the absence of traditional storytelling and the words “this experimental work aims at creating a truly international absolute language.” A cameraman stands atop a giant, uh, camera, steps down, and enters an empty theater which soon fills up with patrons and projectionists who smile at musicians apparently providing an overture. On a screen in the front, we enter a window where a woman awakens to begin her day, segueing to morning light on sleepy, still sections of this uncited Soviet city. Machines sit idle; streets are barely traversed; from high up in an apartment building, we see a convertible car approach and then pick up a man with a movie camera. The car drives the man out to a rural railroad crossing, where the cameraman’s head leans on the rail as a train approaches…followed by bizarre cross-cutting that seems to jar that lazy woman out of bed to start her morning routine. We see many of this city’s poorer people stirring, starting, spraying down street fixtures. World War I-style biplanes are rolled out of a hangar; streetcars and buses roll out of stations and into the urban center, where they are embarked and disembarked upon. The center of the city – marked by a banner that reads “Gorky Park” – rustles with morning-commute hustle and bustle. The cameraman is foregrounded, sometimes climbing scaffolding, sometimes walking through a crowded street, and sometimes with his eye seen through the (over-cranked) camera’s peephole, which creeps out a woman sleeping on a bench. One shot of a crowd surging into a gated area has sometimes been interpreted to signify the emergence of the masses. Many, many more morning shots include miners at work, a mail bicycle, shop-window automatons, spurting fountains, trains in motion, and the film’s first dutch-angle split-screen, which sets off the sidewalk/street against itself. The cameraman stands in a moving convertible, facing sideways, to capture a second car of relatively rich Russians being drawn by a white horse who pulls into a freeze-frame that segues into the editing booth itself, where Vertov’s editor/wife, Elizabeth Svilova, chooses some shots and dismisses others. At her discretion, the action re-starts, the horse-drawn carriage and streets come back to life, and a camera high above the boulevards pivots first to a couple registering their marriage and then turns to another couple registering their divorce. Many, many more urban vignettes culminate in a shot rotating around a female eye blinking intercut with actors, actions, activities. An injured man wipes blood off his brow as an ambulance crew speeds toward – him? Women get beauty treatments; women work as box-makers, typists, cigarette packagers, switchboard operators – one with a conspicuous happiness that is Communist propaganda for women working. We linger inside a steel mill to make out metal smelting. Suspended by cranes on a small platform, the cameraman films a large dam structure that symbolizes Soviet strength and fluidity with uh, fluid for electricity. Back in the city, cuts speed up and footage speeds up. Boats and clouds drift across the screen as we segue to a very crowded beach, where an Asian-descended man leads what may be a yoga class as well as a magic show that delights some kids. Men and women do decathlon events in slow motion as nearby viewers, not in slow motion, enjoy the spectacle. A happy working-class woman caking mud on her skin is contrasted to a disgruntled rich woman applying lipstick. The cameraman shoots the beachgoers and gets cut in half by his own split-screen. Outdoor athletics, like women’s hoops, gets cross-cut with indoor exercise, like women straddling mechanized horses rather erotically. Men, including the cameraman, riding motorbikes on a track are cut with women riding a carousel. In a beer pub, a woman happily drinks with men while the double-exposed cameraman rises from a filling beer glass. Another woman’s target practice includes wine bottles and a woman figure bearing a Nazi swastika. The cameraman walks into an edifice under the banner “Lenin’s Five-Year Plan” so we enter the future, with many, many, triple- and quadruple-exposed, split-screen-y shots of noisemakers. After almost an hour, we return to the frame audience, who delight at the animated movements of what may be a robot camera as well as women dancing to double-exposed piano keys. Shots get shorter and more effects-driven, but the audience members maintain rapturous interest in the summarized, quickened, heightened versions of all the urban activities. In some of the more famous moments, a worker woman smiles in the center of a whirling industrial wheel; the Godzilla-sized cameraman pivots himself over the multitudes; the Bolshoi Theater implodes on itself with angling split-screens. The film finishes with a crescendo of flash cuts, many of no more than 2 or 3 frames, of Svilova, a tram, a traffic signal, and several other impressions culminating in the eye in the lens as the iris closes and the film fades to black.

Man with the Movie Camera wasn’t the hit that Vertov had hoped for. Films without audible words struggled everywhere in 1929. But it was only too convenient for Stalin, now firmly in control of the USSR, to blame the failure of Man with the Movie Camera on Vertov’s artiness that somehow wasn’t quite propagandistic enough.

Universally considered to be the greatest documentary, the film is more avant-garde than that honorific implies; ostensibly a “day in the life” of a then-modern Russian city, this film adroitly innovates and deploys multiple exposure, split screens, tracking shots, various cuts, slow and fast motion, and various modes of self-reflexivity.

Influenced by: city films; Vertov’s wife Elizaveta Svilova edited it and probably deserves equal authorial credit

Influenced: “cinema vérité” was named after Vertov; considered a leading example of Pure Cinema; sometimes called Soviet propaganda

~

D7. Enthusiasm (Vertov, 1931) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by MacKay read analysis by Bradshaw listen to my podcast

Joseph Stalin ordered Dziga Vertov to Ukraine to make a film about the great successes of his Five-Year Plan. This did not turn out quite the way Stalin expected. Vertov absolutely understood that his job was to show how well the Five-Year Plan was working in Ukraine’s Donbas region. But Vertov felt that some artistic creativity would make the film more, not less, appealing and therefore better propaganda. Specifically, Vertov wanted to make the microphone as much of a character as the camera had been in Man with the Movie Camera. Showing a rural woman hearing the story was a sort of fourth-wall-breaking way of revealing the power of industry, the efficacy of the Five-Year Plan, and the beauty of sound. Sometimes, this took the form of presenting sound as though it were out of sync, something Stalin apparently didn’t love.

Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass begins with a medium shot of a young woman in some sort of rural repast putting on headphones. She seems to “hear” the subsequent visual scenes of people making the sign of the cross at a suspended statue of Jesus and an elaborate Russian Orthodox Church. On headphones, our young woman is told she will hear the Symphony of the Donbass, and we cut to a medium shot of a young conductor. Cuts suggest that the young woman sees – by hearing – churchgoers emerging outside, praying, genuflecting, and kissing the feet of a bas-relief of Jesus. Bolsheviks bearing banners march into the city, cross-cut with the church’s evident religious symbols. An organizer says “The Pope is chained to the cash drawers of the capital,” followed by a life-size puppet of an evil pope, followed by another man suggesting that the bell towers come down. Angling split screens mash together church edifices while the marching workers ransack the church and march out with paintings and crosses to their co-marchers’ ebullient cheers. With the help of ladders and cables, the peoples collapse the steeples to tumultuous applause. In effects shots supplemented by assonant noises, Communist stars and emblems rise where the high towers were. A workers club edifice gets a lot of emphasis as happy young females are seen in happy closeup, compared with a statue of a bold strong Communist. An art-installation assembly line rolls out suitcase-sized versions of cars, crops, and other staples adorned with the words “toward socialism.” At dusk, we see silhouettes of laborers coming from large industrial plants as a narrator says “this happened in Donbass in the Five-Year Plan era in 1930.” The proletariat fills up a 1000-seat movie theater which shows them one word onscreen, translated as “out of stock,” followed by a voice associated with the heroic statue that tells them to give the country the coal it deserves. About 30 minutes in, a middle-aged man delivers the film’s first (only?) monologue to camera, extolling the collective efforts of the best workers and, uh, all workers. Coal miners get trained while trained coal miners do many routine tasks. After many more shots of machines making and moving coal, we see a large group, heralded as the best of workers triumphantly enter Donbass. Miners do some of the more thankless tasks, like fire-suppression, as the narrator says, “It is about glory. It is about courage and heroism.” At ovens, men harden coal into steel rods, which get carried by trains out of the region. Abruptly, we find ourselves in agrarian fields, where women sing while piling hay and we join a rural meeting whose leader praises socialism. In some more urban setting, men march together in happy strides as a narrator says “long live collectivization.” We depart the proletariat parade to return to the rural gathering, where a wide shot of peasants dancing is double-exposed with close-ups of happy young women. An out-of-tune accordion plays over horses and workers happily marching past a rural combine that receives hay, in a new medium shot, from a sturdy, pretty woman. The final shot is the dissonant, assonant, rural parade.

The structure is interesting, because the first 15 minutes contain this somewhat shocking, at least to my modern eyes, proletariat sacking of a church, and only five film minutes after that sacking does a title tell us that we’re in Donbas. It seems like it might have suited Stalin better to present the church looting as though it were clearly in Donbas, but instead we are invited to think that it must have happened elsewhere, presumably closer to, or in, Moscow. One way of seeing this is that Vertov and Svilova simply wanted to present the truth as they filmed it. Another way is that they’re trying to tell us that the people of Donbas are as yet too simple to destroy a church, although maybe they’ll get there in the next movie.

So what is the propagandistic value? Was Stalin right to worry about the intentionally off-sync sound? How can we understand this film now that we know the terrible price Ukrainians paid for the Five Year Plan? To be clear, Vertov did not see the Holodomor, the 1932-33 Stalin-made famine, and because Enthusiasm failed, it’s hard to make a case that this film “excused” Stalin’s treatment of Ukraine. Not enough people saw it. However, should Vertov get debit for trying?This, the first Russian sound film, is a ground-level and underground-level (coal mine) view of Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan and its machinations centered around Donbass; compared to Man with a Movie Camera, this is both more avant-garde and more propaganda for Soviet Communism, which makes for a fascinating and singular combination

Influenced by: Man with a Movie Camera; Stalin; again, Vertov’s wife Elizaveta Svilova edited and probably deserves equal authorial credit

Influenced: cinema vérité, named after Vertov

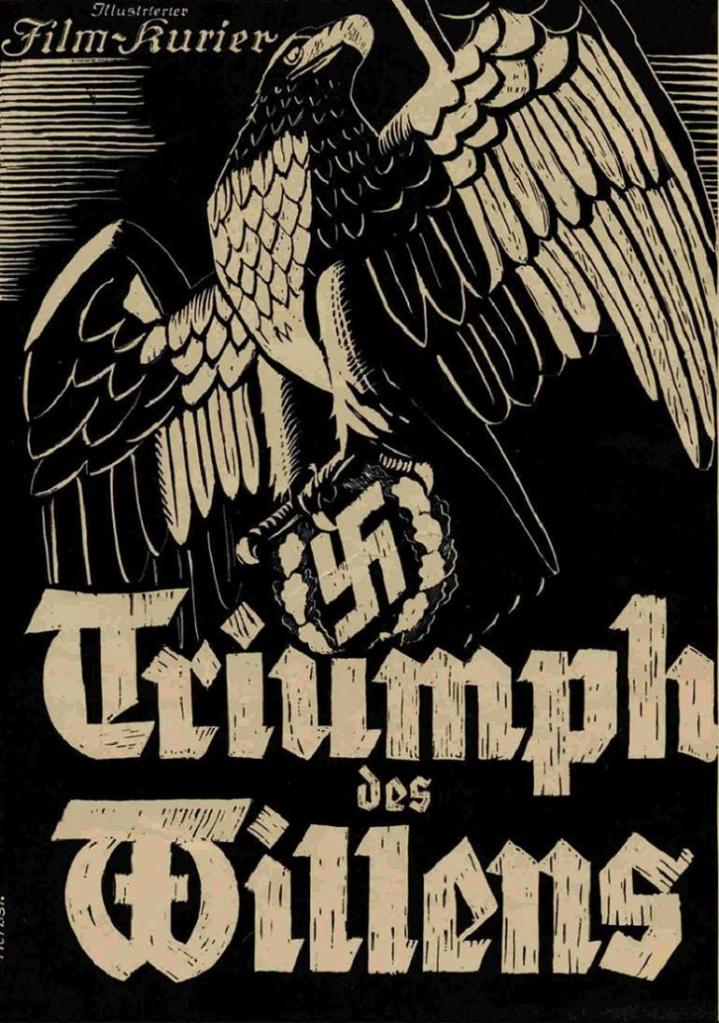

D8. Triumph of the Will (Riefenstahl, 1934) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on amazon watch analysis by Ideas read analysis by Hagopian listen to my podcast

“The documentary of the Reich Party Congress, 1934, produced by order of the Fuhrer”

There’s no “great film” inside or outside the world of documentary quite as notorious as The Triumph of the Will. The Holodomor was part of the context; in January 1933, while Stalin was proving a new efficacy of dictatorship by killing millions of “his own” people, Germany found itself voting for heavy-handed reprisals by electing Adolf Hitler to power. However, Hitler had no intention of governing from the shadows like Stalin, but instead saw himself more like and more than Mussolini, making speeches and proving his power through pageantry, parades, and all that pomp and circumstance. Hitler needed the right person with a camera – talented but also something of a true believer. He probably half-fell in love when he watched The Blue Light, directed by and starring Leni Riefenstahl as a young, tall, Aryan-looking, sybaritic witch whom the locals ostracize but need anyway. (This was also co-written by Carl Meyer.) When the real-life Riefenstahl blamed Jews for some of the film’s bad reviews, Hitler knew he had his replacement for Walter Ruttman as his chief videographer.

Riefenstahl, for her part, described in her memoir the first time she heard Hitler speak at a rally in 1932, before Hitler took over the Bundestag: “I had an almost apocalyptic vision that I was never able to forget. It seemed as if the Earth’s surface were spreading out in front of me, like a hemisphere that suddenly splits apart in the middle, spewing out an enormous jet of water, so powerful that it touched the sky and shook the earth”

In the same memoir, Riefenstahl claims that she made documentaries about Nazi parties only to pay the bills and as a means toward other projects. She claims that she hadn’t really meant to make The Triumph of the Will, but did because international funding for a fiction film fell apart. She also claimed not to know about certain atrocities, starting with The Night of the Long Knives in 1934, when Hitler ordered the deaths of several close associates who had figured in both of Riefenstahl’s first two documentaries for the Fuhrer. I could go on and on about claims and counter-claims, but I think it’s time to get to the film. Essentially, Hitler expected, and received, about a million Germans turning up for a week of rallies in 1934 in Nuremberg, and hired Riefenstahl to make the best possible film of it. One might say that the results are the world’s worst best film.

The Triumph of the Will begins with a magisterial overture in darkness finally giving way to an eagle statue and teutonic-fonted title cards that situate us in September, 1934, 20 years after the start of the war, 16 years after the “beginning of the German suffering,” and “19 months after the beginning of the German rebirth” when the Fuhrer flew to Nuremberg to, uh, “review” his followers. The film’s first moving images are from a plane, moving through billowy cumulus clouds until we see its shadow over the medieval, swastika-bedecked buildings of Nuremberg. Enthusiastic crowds line up to cheer the plane’s landing as well as the motorcade that begins winding its way through the city. The film builds anticipation by showing us the back of the head of the Chancellor for about a minute while he recognizes the throngs, stands in a moving car, holds his hand held behind his upraised wrist, and nods approvingly. Finally, we get a good look at Adolf Hitler as his motorcade arrives in an overjoyed mass of people in the city center, and the sequence ends with Hitler waving from his hotel window over light bulbs that have been arranged to spell out Heil Hitler. At night, music and fire indicate more celebrating outside Hitler’s hotel. In the morning, worshipful shots of high buildings dissolve into a grid of hundreds of tents of German Youth, sometimes called Hitler Youth, who are soon seen playfully shaving and hosing off and wood-gathering and cooking to the sounds of an off-camera chorus singing heartily. In what look like boy scout uniforms with swastikas, the boys playfully wrestle, race, and get rambunctious. In daylight, Hitler emerges from his hotel to handshake a few hausfraus and handsomely dressed Hitler Youth. At night, in Nuremberg Hall packed with thousands of seats, German ministers take turns extolling the virtues of Hitler and the government’s current programs. One, Julius Streicher, says, “A people that does not protect the purity of its race goes to seed!” to loud cheers. During the day at the town-sized Zeppelin Field, trumpets blare to herald Hitler ascending a platform to “inspect” 52,000 “labor men” bearing shovels like bayonets, proclaiming loyal slogans, tasks, and aspirations, but also individually naming their various homes. Hitler speechifies that Germans will no longer look down on manual laborers and in fact be forced to do some labor themselves as the men march in unison. We visit the “Stormtrooper Night Rally” where singers bearing torches sing of “the cult of darkness and fire” and cheer on exhortations to victory. During the day in an enormous stadium, tens of thousands of young men line up, raise hands in the Nazi salute, and stoically listen to Hitler’s speech telling them to be both peace-loving and strong as they represent an eternal Germany. We pan down from the twilight clouds into the “Night Rally of Political Leaders,” where men bearing swastika flags march into Zeppelin Field to hear Hitler address recent German problems by proclaiming “the State does not order us, we order the State” and asks everyone to vow to commit to Germany to a chorus of “sieg heil”s. In perhaps the film’s most quoted clip, during the day, from 45 degrees above, Hitler, flanked by two lieutenants, walks past tens of thousands of quietly respectful Germans on his way to the tomb of the unknown soldier, where this trio pays their respects. Hitler turns, crosses back through the stadium, ascends to a concrete podium, gets dwarfed by building-size swastika flags, and claims that anyone who tries to do harm to the gathered army will harm only themselves. Cannons blast in salutes while Hitler is seen in medium shots shaking hands with officers. Nuremberg’s citizens line its streets with reverent salutes and cheers first of Hitler standing in a car at the front of a motorcade, and then of marching, militant, meticulously regimented Movement Men. To mutual longarm strongarm salutes, the Germans goose-step through a large square that has apparently been renamed Adolf Hitler Platz. Night in a Nazified Nuremberg Hall, under a sign saying “Deutschland Uber Alles,” begins with the now-standard pomp and circumstance leading up to one more speech from Hitler, who celebrates the strength and courage of millions of National Socialists whom he names as “the one and only power in Germany.” Hitler declares, “Because these are the racially best of Germany, they can claim the leadership of the Reich and the people,” and such race-based hierarchy will ensure a Reich that can last a thousand years. Rudolf Hess mounts the podium and adds a coda: “Hitler is Germany, and Germany is Hitler,” as the Nazis sing one final, creepy dirge about marching in spirit.

The movie played all over the world, won many awards, and firmly established Leni Riefenstahl as the world’s pre-eminent documentary filmmaker as well as its pre-eminent female filmmaker. After the war, for more than a half-century, Riefenstahl claimed that she never meant the film as propaganda and was disgusted that it was ever used that way. This explanation seemed sufficient for the many, many people who hired her and consorted with her, including many well-known names. Riefenstahl died at the age of 101 in 2003.

For decades, we have been grappling with the Triumph of the Will. Should students see it? Should anyone see it? Can art be made of this sort of subject matter?

Influenced by: the Nazi party’s considerable resources and willingness to stage things

Influenced: debates about film morality; Star Wars; also, Riefenstahl spent two-thirds of the 20th century as its most celebrated female filmmaker

~

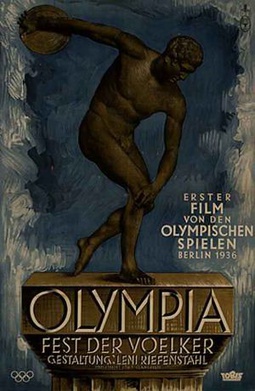

D9. Olympia Part 1 (Riefenstahl, 1938) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by Teng read analysis by Barber listen to my podcast

“The fastest sprinter of America, Jesse Owens, at the start.”

The story of the making of Olympia began four years before the release of the Triumph of the Will, when Leni Riefenstahl was a non-directing actress, in 1930 in Berlin, where several nations bid on hosting the 1936 games, and they were awarded to, uh, the host nation of Germany, partly as an endorsement of the Weimar Republic which…would be swept out of power in 1933 by Adolf Hitler, who was so impressed with the director-star of 1932’s The Blue Light, Leni Riefenstahl, that he commissioned her to direct a couple of pro-Nazi documentaries. Hitler and Riefenstahl both noticed that the 1932 Summer Olympics, despite taking place in the home of the movies, Los Angeles, were not filmed. (Those L.A. Olympics, taking place in the nadir of the Depression, tightened many belts for the few nations that did attend.) Hitler was happy to devote Nazi resources to the first-ever Olympic documentary. He built a 100,000-seat stadium specifically bigger than the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, organized the first-ever torch relay of the Olympic Flame from Greece to the host country, and commissioned Riefenstahl’s state-of-the-art filmmaking.

Many of Riefenstahl’s innovations became standard for capturing any sport on any screen. Cuts from closeups of athletes to closeups of happy spectators bridged the distance between Olympian and civilian. Riefenstahl organized tracking shots from bleachers, dollies on sprinters, cameras rising on balloons, and even an underwater camera that could change focus as it landed in the water. It’s hard to think of another documentary that so clearly surpassed the scale and scope of its antecedents.

Opening titles are engraved on a wall in the classical Roman font (think SQPR), recognizing the modern founder of the Olympic Games alongside film director Leni Riefenstahl. We begin on somber-scored, twilit shots of the Parthenon and similar ruins that gradually become better lit, more hopefully scored, and transitioned to statues of apparent athletes of antiquity who, at the 7:30 mark, segue into modern competitors posing and gesturing athletically and balletically. In abstract darkness, a man lights a torch and begins marathon-running through non-abstract stadiums and lined-up crowds, eventually passing the torch to another runner, whose running segues into a map that we trace, with the aid of titles, from Greece to Bulgaria to Yugoslavia to Hungary to Austria to Germany, signified by a genuine and gargantuan modern stadium, swastikas, a close-up of Adolf Hitler, and thousands giving him the “Sieg Heil” salute. During the parade of this event’s 51 nations, when the snappily attired athletes march through the stadium, the modern viewer cannot help but notice the countries’ athletes that “sieg heil” to Hitler: Greece, Italy, Austria, France, and of course Germany, but not Japan, India, the U.K., the U.S., or anyone else on camera. Hitler “sieg heil”s the heilers and declares the Olympic Games open. The torchbearer runs into the stadium to light the Olympic flame, which occasions a hymn to the greatness of competition, “Olympia,” perhaps sung by some of the attendees but certainly sweetened by an off-screen chorus. Announcers from a half-dozen countries introduce, in their respective languages, the men’s discus throw, which eventually concludes with a gold medal for the USA. Athletes’ movements are sometimes slowed and sometimes sped up; sound is sometimes presented as a cacophony of fans, and at other times hushed to silence as the athlete pivots. Second is the women’s discus throw, which ends with a new Olympic record and a gold medal for the German, whose discus travels about as far as that of the winning women’s javelin throw, 47 meters and change, presented third. The filmmaking offers very occasional abstractions; Germany wins gold and silver at both women’s javelin and men’s hammer throw; an Italian wins the women’s hurdles. Just before a men’s 100-meter heat, our German announcer points out Jesse Owens, of the USA, who goes on to win the heat in 10.3 seconds and then a later world-record heat that is disqualified because of a tailwind. After Owens wins the real 100-meter dash, he is seen smiling to his countrymen’s effusive cheers even as no Germans are shown. A Hungarian wins the women’s high jump, followed by a German winning the men’s kugelstoss, or shotput. String music is heard with more frequency as an American man wins the 800 meter race and a Japanese man wins the triple jump. The German announcer hails Jesse Owens as the fastest man alive as Owens proceeds to compete in, and win, the long jump, with a new world record. Sometimes we see closeups of a happy spectator; sometimes this pleased person is Hitler. In the 1500 meter race, Holland pulls ahead from the pack and sets another world record. In the men’s high jump, the bar is set to 1.85 meters during trials, then to 2.03 meters when the field is narrowed to four, one from Finland and three from the USA, who ultimately win gold, silver, and bronze. In the hurdles, the U.S. only win gold and bronze; the U.K. takes the silver. After the film slows to observe the javelin throwers, a German manages to triumph over two Finlanders, and when the Nazi swastika rises above two Finland flags, we hear the crowd singing “Deutschland uber alles.” However, the very next shown event is the rather dramatically presented 10,000-meter race, during which Finland wins bronze, silver, and gold. For the first time, an event stretches into nighttime as pole jumpers leap and bound until finally, an American man triumphs over a Japanese man. Sped-up footage makes runners appear even faster than usual in a relay race which Britain eventually wins. Quite appropriately, or not, the final event presented is the marathon, a 42-kilometer race that begins in the stadium and moves out to the hinterlands around Berlin, with music rising to the sight of closeups of road shadows of footsteps, until finally…Son Kitei of Japan re-enters the stadium to uproarious cheers and a gold medal and the sight of competitors’ suffering feet. At night, the stadium glows and flies flags and seems to sing “Olympia.”

During almost two years of post-production, Riefenstahl came to understand that she had two movies’ worth, and indeed many countries saw both Olympia Part 1 and Olympia Part 2, each about two hours long. Some histories say there were three versions of each film, in German, French, and English, but in fact there were many more if you account for Riefenstahl’s habit of re-editing after she regarded viewer reactions. Almost every version wound up winning an award, including at the Venice Film Festival in September 1938, where it won the Golden Lion over Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Harboring no hard feelings, Walt Disney went out of his way to show Riefenstahl around Hollywood when she arrived two months later just before the planned American premiere of Olympia…which was cancelled after news arrived of the brutal Nazi pogrom that would come to be called Kristallnacht. Olympia premiered in the States two years later, in specialized screenings in 1940, as a sort of substitute for the cancelled 1940 Olympics. One likes to think that Hitler didn’t start the world’s worst war just to ensure that Riefenstahl’s film would be the last film of the Olympics for 12 years – because of the war, the Olympics didn’t happen again until 1948 – but those circumstances probably also contributed to the film’s reputation.

So that brings us to: is this all Nazi propaganda? Scholars differ.

nfluenced by: the Nazi party’s considerable resources and willingness to stage things

Influenced: Olympics coverage and TV sports coverage, forever

~

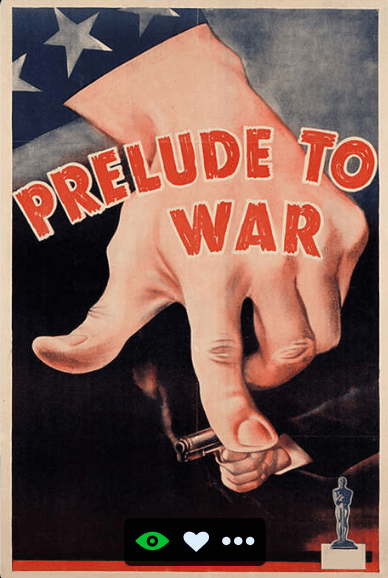

D10. Why We Fight: Prelude to War (Capra, 1943) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on YouTube watch analysis by McParland read analysis by Bohn listen to my podcast

“How did it become free? Only through a long and unceasing struggle inspired by men of vision: Moses, Muhammed, Confucius, Christ.”

After the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, American film director Frank Capra, along with about half of America’s then-famous men under the age of 45, enlisted in the armed services. Yes, Capra was 44, and yes, Capra was famous, despite “only” being a film director, as proudly explained in Capra’s autobiography “The Name Above The Title.” Capra was known for dramatizing quintessential American values, was already derided by some critics as “Capracorn,” and was likely endeared to General George Marshall for both reasons. Marshall, who was running America’s war effort, hired Capra to direct documentaries that would explain and justify the war to skeptical recruits. Marshall placed Capra in an office next to him in Washington DC, impressed upon him the sacredness of the job, and screened for him Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will. In his book, Capra said that the task of countering Riefenstahl without expensive studio machinery seemed close to impossible for several days until he thought of the Bible passage “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free.” Capra planned to show American soldiers enemy propaganda films re-organized and narrated with a no-nonsense American sensibility. Of course, this would require, ahem, re-appropriation on a theretofore unseen scale, and in 1942 it wasn’t exactly easy to obtain enemy films without explaining why one wanted them. Nonetheless, eventually, a few heroes working a few unofficial channels managed to get Capra the footage he needed, although Capra still wanted to, ahem, “re-create” a few scenes and did.

As for Walt Disney, he may have been impressed with Riefenstahl’s technique, and some of his films may have taken advantage of anti-Semitic stereotypes, but make no mistake: after Pearl Harbor, Walt Disney put his mini-studio at the command of the U.S. government, not least because most of his animated features had yet to be released in Europe and he needed access to that market if he was ever going to break even. This is a long way of explaining why Disney fought, or why Disney Studios created the animation for all seven of Capra’s Why We Fight films. As for the blackness that represented enemies and the whiteness of Western powers, Disney didn’t invent that, but was following convention established in magazines like “Time” and newsreel producers like “On the March.” Shall we march into this?

The opening titles of Why We Fight: Prelude to War explain that its content is “an indispensable part of military training and merits the thoughtful consideration of every American soldier.” Our narrator, Walter Huston, shows U.S. soldiers marching and asks us why, or really, keeps asking if the reason is Pearl Harbor or country after country after country, each visualized by recent warfare, bombings, and carnage. Huston asks why our country, recently peaceful, has overnight become an arsenal “ready to engage the enemy” everywhere, and when the film quotes Vice President Wallace that this is “a fight between a free world and a slave world,” we are given the visual aid of a white free world and a black slave world. Regarding the former, Huston quotes men’s visions that gave us our freedom, namely Moses, Muhammed, Confucius, and Christ, whose insights found their way to “All men are created equal” and “That government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.” Regarding the latter slave world, Huston claims that after the devastating world war, unemployed, desperate people turned to leaders who took away their freedom in favor of cheap stunts and, eventually, militaristic imperialism. The film, made by an Italian-American, does not generalize about the Italian character but does note the “regimented discipline” of Germans and the “fanatical devotion” of the, ahem, Japs, as it cycles through a series of incriminating visuals, dissolves, effects, and stock footage. Huston explains that in Italy, Germany, and Japan, legislatures have become rubber-stamps, newspapers have been shut down, the press is controlled by a single party, and courts and juries and labor unions have been eliminated. In a jumpy, double-exposed montage of newspapers and dramatic vignettes, Huston shows how brute force has been suppressing dissent, even from churches, as children are instead now taught that the head of state is their God. Back in the white, I mean, democratic world, Huston presents multi-state anti-war treaties of the 1920s that resulted in the reduction of 60% of the U.S. navy, an army made smaller than Romania’s, and a prevailing attitude of peace through isolation, symbolized by several “men on the street” who want nothing to do with Europe. While Americans could read any book, worship at any church, vote for any man, and get a kick out of watching their kids grow up – as seen in Norman Rockwell-ish shots – the people of Italy, Germany, and Japan are seen overruled and overprepared for military conquest. Without a hint of irony, Huston excoriates foreign propaganda services that broadcast lies, lies, lies, about us being the haves while, they, the have-nots, took billions away from food programs to make the largest army the world had ever seen. Huston claims that the Tanaka Memorial, a 1927-written plan for world domination, began its activation when, as we see in lively re-creation, Japan took over Manchuria in 1931 and the rest of the world stood idly by as the League of Nations and communal responsibility became dead letters. Emboldened, in 1932, Japan attacks Shanghai, a city where we see women mourning graphically slain children and men beating back Japanese soldiers. Over in Italy, Mussolini apparently follows Japan’s example by invading and conquering Ethiopia, with its leaders correctly guessing we, the West, would not fight for mud huts in Ethiopia or Manchuria. As Huston promises more explanations in the next film, he summarizes by saying that this isn’t just a war, it’s the common man’s struggle between us or them, a free world or a slave world, and that 170 years of freedom “decrees” our answer as a Liberty Bell swings.

The Tanaka Memorial probably never actually existed, although many Americans honestly believed in it even before they saw Why We Fight. How many Americans saw any or all of the Why We Fight films? Marshall meant for the seven films to be seen by every single recruit, although colonels maintained some latitude over what was actually screened on their bases. President Roosevelt loved the films so much that he wanted them released in theaters, and the studios dutifully complied. The first one, Prelude to War, was the most financially successful; after a while, people tuned out 1930s’ geopolitics in favor of tuning in to the most recent battles. But there was another reason for the diminishing returns: some prominent critics, including Lowell Mellett, an aide to FDR, felt that the films were dangerous and might create hysteria that would be hard to manage after the war.

In a sense, Mellett was right, because Capra perfected many propaganda techniques that would be used for decades in a wide variety of contexts. Sometimes these techniques were mobilized for good causes, as in a short film that Capra supervised called The Negro Soldier, which was the first time any piece of cinema had acknowledged African-American contributions to U.S. history. More often, the Capra/Riefenstahl techniques would be deployed on behalf of more questionable enterprises. This is a big part of the reason why critics assembling their all-time-best lists have mostly ignored documentaries that came out during the decade after World War II. It’s also true that most of the documentary energy migrated to the new medium of television and its nightly news broadcasts.

Influenced by: The Triumph of the Will; Capra and Huston’s personalities; war imperatives

Influenced: propaganda; taught Americans how to hate

~

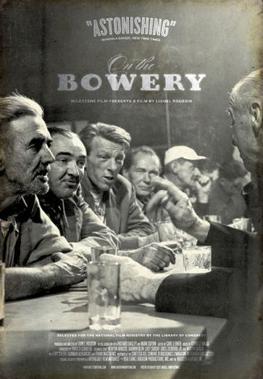

D11. On the Bowery (Rogosin, 1956) BO clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on criterion watch analysis by Turan read analysis by Wright listen to my podcast

“Will you get out of here? Get out of here!”

American TV covered the news, but then, like now, TV was less successful at visualizing endemic problems, for example racism, sexism, health care injustice, or poverty. Enter Lionel Rogosin, a child of privilege, the Yale-educated son of a textile mogul who, while being groomed to take over his father’s business, detoured to serve in World War II, and wound up interested in, and traveling to, Eastern Europe, Israel, and Africa. He worked crew on a United Nations film called Out, about Hungarian refugees, during which he taught himself to use a Bolex. Rogosin wanted to make a film about African apartheid, but felt he needed to hone his skills a little closer to home where, it happened, there was apartheid.