Of all the collections on bestlovedfilms, this would be the easiest (and most enjoyable?) to attempt to view at home in a reasonable amount of time. Welcome to the avant-garde, the best-known films by the innovators who pushed the envelope on formal style, permitting larger-budget directors to follow in their wake. This gallery does not include lost films, popular music videos, or almost any feature-length films; the latter two have a greater purchase on the mainstream, while this collection attempts to tell the story of the forward-thinking filmmakers who mostly worked in obscurity.

E1. Dickson Experimental Sound Film (Dickson, 1895) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

The true film scholar will know about all the early breakthroughs from Muybridge to Marey to Lumieres. Mostly, these were what we now consider documentary (or proto-documentary). The spirit of experimental cinema, as this gallery will amply demonstrate, tends to exist somewhere between fiction and non-fiction although of course there are exceptions.

The Dickson Experimental Sound Film was chosen partly for having the word “experimental” in the title. But also, compared to many of its 19th-century peers, it was truly bold and innovative and about as far-seeing as one might hope for. Anticipating arguments that would find full flower more than 30 years later, Thomas Edison and William Dickson were the first to formally attempt to marry sound and image. The truth is that the sound portion was long lost, found only in recent decades, and its currently apparent synch with the picture is only provisional. Nonetheless, considering the parameters of the attempt, this makes a fine “first” experimental film. Edison’s Black Maria studio was unfortunately named in the sense that everyone working there was white and male, which is probably one reason that the pair of dancers are male. Nonetheless, it remains remarkable that this cinematic milestone was in any way queer-positive during the same year (1895) that Oscar Wilde was sent to prison for violating sodomy laws.

This 45-second film is one shot which consists of two men dancing on the right side of the frame while, at center, a third man plays a violin near a giant horn that presumably captures his music. A fourth man appears near the horn, but his activity isn’t very clear. That’s it.

A useful frame for understanding Edison and Dickson’s films was provided by Tom Gunning, among others, whereby the American innovators are compared to their French counterparts, the Lumiere brothers. The Lumieres’ films are generally filmed outside, welcoming spontaneity, capturing life as it apparently is. Edison films are generally filmed inside the Black Maria studio and elaborately choreographed. This shows two ways film could or would go. Of course, this isn’t the only narrative; Dickson and Edison would eventually get out in the world. But back in the Cleveland administration, films like The Dickson Experimental Sound Film were striking for their hermetic, forced qualities, and perhaps the humanity that shines through in spite of all that.

Influenced by: In about 1891, Edison and Dickson became two of the people who invented what we now call motion pictures, and they made dozens of shorts before and after this

Influenced: well…all of screen content

E2. Cinderella (Cendrillon) (Méliès, 1899) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

Georges Méliès made more than a hundred fictional shorts before he made Cendrillon, but it was his, and the, first to become a major success, paving the way for A Trip to the Moon. He advertised it as a “grand faerie extraordinaire” with 20 tableau – actually, it has about five, but this was four more than Melies had had. For Cendrillon, Melies made the first film to consistently use the dissolve as we know it now, to transition between space and a long amount of time.

Melies based the sets on then-current conceptions of Cendrillon via authors like Gustave Dore. The first shot’s rapid departure of Cinderella’s superior caretaker indicates that either the beginning of the film is lost or that Melies could rely upon his audience’s familiarity with the Cinderella story. As it turns out, the story dates back to Ancient Greece during the lifetime of Christ, although the modern version was written by Charles Perrault about 200 years before Melies’s film. Perrault coined “Cendrillon,” which was Anglicized in Britain to “Cinderella.”

Melies pioneered many of the conventions of fiction film, particularly of the fantastical variety. From a distance, it may be hard to appreciate how radical and experimental he was. Working in the 19th century, Melies innovated the sort of formal gestures now associated with the 20th, including elaborate effects, continuity editing, and the liberal use of pre-existing intellectual property. For certain premium versions, Melies used Elisabeth and Berthe Thullier’s color lab, which employed about 200 women, who, in the case of Cendrillon, hand-painted carefully chosen colors onto gowns.

Cendrillon, wearing rags, watches forlornly as one of her ostensible stepsisters, dressed in a resplendent gown, leaves. Out of nowhere, Cendy’s fairy godmother appears, turns three little mice into three coachmen, turns a pumpkin into a ornate carriage, transforms Cendy’s rags into a lovely gown, nudges her onto the carriage, sees it roll away, and disappears into the floor. This has all taken place in one frame, without camera movements, with felicitous editing, in one minute and 25 seconds. Dissolve into another minute-long shot, liberally cut, where Cendrillon attends the royal ball, dances with a handsome courtesan, sees the sudden “poof” appearance of an old long-bearded man with a clock who points to midnight and poofs away, sees her fairy godmother return and transform her gown back into rags, and feels the crowd bum-rush her offscreen even as the courtesan recovers her shoe. Dissolve to a bedroom in her humble home, where Cendrillon sees visions of clocks changing back and forth to dancing women as though to taunt her with time. After, in the same shot, two begowned stepsisters scold Cendrillon just before the courtesan enters, tries the slipper on the two rich women, tries it on Cendy, and gets a match, prompting the fairy godmother to reappear and magically re-gown Cendy just as she leaves with the courtesan. Dissolve to the last framing (with edits), with eight girls standing on the stairs outside a church, where Cendrillon and the courtesan appear, wed, and withdraw inside, prompting the girls to elaborately dance before the crinoline behind them is pulled back to reveal the whole happy cast.

The first four minutes of Cendrillon may well represent the most economical, most efficient, even best-told version of the Cinderella story that modern audiences have ever seen. And then, the last two minutes are almost entirely extraneous, or perhaps whimsical. Nonetheless, the film clearly demonstrates narrative fluidity combined with formal risk-taking. And audiences responded: after more than 100 films that barely broke even, Cendrillon was Melies’ first big success. Maybe it was the dissolves.

Modern audiences are sometimes put off by the histrionic performances and the proscenium staging – that is, every set is positioned as though to a 500-seat audience, without camera movement. But if one considers the other leaps that Melies was asking of viewers, one appreciates that he was smart not to alter dominant acting styles or move the (very heavy, refrigerator-like) camera all around the stage. Think if your favorite envelope-pushing filmmaker – say, Quentin Tarantino – were also filming half his movie upside down. You can only push people so much at one time.

Influenced by: magician Méliès saw the Lumière brothers’ actualities, made many of his own, began using the cameras for magic, and made an average of two short films a week for the next decade, developing his technique into this film’s level of mastery

Influenced: further experiments; the pivot toward fiction; specifically, Cecil B. DeMille

E3. Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon) (Méliès, 1902) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

What inspired the most influential film ever made? Jules Verne’s “From the Earth to the Moon,” H.G. Wells’s “The First Men in the Moon,” Jacques Offenbach’s opera-faerie “Le voyage dans la lune” (an unauthorized parody of Verne’s books), and one of the first so-called “dark rides,” an indoor, tableau-heavy amusement park ride called A Trip to the Moon at the 1901 Pan-American Exhibition in Buffalo. But Melies also brought five years of his own innovations making literally hundreds of films; Ron Miller wrote that A Trip to the Moon used “every trick he had learned or invented.” Because Melies wanted this film to be special, he lavished considerably more time and money than he had on previous films, particularly on the sets, costumes, and masks. The finished film was also much longer than any of his previous films, at least 14 minutes depending how it was exhibited.

By 1902, Melies could be said to have the world’s first regular filmmaking routine. In his greenhouse-like studio, the morning would be spent on script revisions, the lightest part of the day would be used for filming, the late afternoon would be lab work, and then Melies spent most evenings attending Parisian theatre. It was there that Melies found most of his actors, paying them a franc a day for film work, which was more than they made on the stage.

The most famous shot of pre-1915 cinema was accomplished not with camera movement, but instead with an actor in a moon mask, his body covered by black velvet, on a track slowly approaching the camera just before the rocket hits the moon’s “eye.”

This site is not in the habit of recommending reading wikipedia; however, the wiki of Le Voyage Dans La Lune is rather excellent, and almost as much of a narrative triumph as the film it discusses. For devotees of this film, this wiki is basically the perfect introduction to and immersion into the film, without me really needing to add more.

A Trip to the Moon begins with the most complex static three-minute shot that most film fans will ever see. The complexity consists of the fanciful Astronomical Academy set, the 25 actors, or scientists, wearing conical hats (a clearly integrated group), the six girls who come on and off to hand telescopes to scientists in the front, the telescopes morphing into stools, the one scientist advocating a trip to the moon, another fiercely debating him, a hubbub, and a morphing of clothes as several in the room march offstage on their way to the moon. Dissolve into a one-minute shot of the building of the bullet-shaped spaceship. In the next shot, scientists on a balcony observe the heaving smokestacks of factories apparently providing the power for the rocket. In the next shot, young women dressed as sailors in short shorts help the elder male scientists board the rocket and then push it into a launching chamber. In the next shot, the lady sailors blare trumpets just before the launch is fired, causing well-dressed Parisians to enter and cheer the successful launch. Framed by clouds, the moon gets closer and closer to us making its face clear just before the rocket suddenly appears in its right eye, disturbing the face. In an example of elliptical editing – the same event being presented twice – we dissolve to the jagged lunar surface where we watch the rocket land and the scientists disembark, watch an Earthrise, watch the sinking of their ship and some stalagmites, and lie down to sleep. In the same frame, a comet rolls by, the Big Dipper appears with faces in each star, and more heavenly bodies appear, one of whom, sitting like a trapeze artist in a crescent moon, summons a snowstorm that causes the men to wake and seek shelter. In the next shot, in a fungus-filled cave, the leader places his umbrella on the floor where it morphs into a mushroom, grows, and seems to call forth Selenites, or moon men, who gesticulate wildly and get poofed into puffs of smoke by the leader with a new umbrella. However, the tables have clearly turned by the next shot, where in an alien, ornate throne room, the Earthlings are marched in as prisoners, but the leader somehow breaks his bonds, removes the alien king from his throne, throws him to the ground, poofs him away, and then leads his fellow humans to escape offstage. In the next shot, on the moon’s surface, the scientists run from the spear-brandishing Selenites, except for the leader, who turns back, bangs a couple with his umbrella, and poofs them away. In the next shot, the rocket clings to the edge of a cliff while the lead scientist confirms the others are inside, fights a Selenite, grabs a rope dangling from the rocket, and pulls it over the cliff, although a Selenite hitches a ride on the back while his cohorts look frustrated at the escape. In the next shot, the rocket falls from the Moon to Earth, cutting to a shot of the rocket splashing down in a body of water, cutting to underwater where the rocket plunges, lets off steam, and ascends. At a pier, a boat tugs the rocket into harbor even as the leader and the Selenite remain in their places. In a central square with a parade-like atmosphere, the female sailors roll in the upturned rocket and watch as the lunar explorers arrive and receive, from an official, plate-sized moon medals that they proudly wear as someone brings in the Selenite, who wears a chain around his neck, freaks out in protest, but then seems to join in the dance and merriment. In the final shot, revelers dance in front of a statue of the leading scientist having conquered the moon.

These days, A Trip to the Moon is read as anti-imperialism, perhaps a comment on France’s colonial adventures in Africa. However, I’m not sure current first-time viewers see it that way. Le Voyage dans la Lune, on a surface level, seems very much to celebrate its imperialist lead male. These contradictory readings, sutured together by state of the art special effects, is one measure of how this film proved foundational for science fiction and blockbusters more generally.

A Trip to the Moon was the hit that Melies designed it to be, proving popular all over the world, where it was often pirated. Melies chased the pirates for years, mostly unsuccessfully. Nonetheless, A Trip to the Moon was seen by many, many people who had never or barely seen a clearly fictional film, establishing new possibilities for the young medium. In many ways, Melies, who plays the film’s lead scientist, really was the first person to set foot on a new world.

Influenced by: the Lumières; Jules Verne’s stories;

Influenced: considering its effects, sensibilities, age, and renown, this is arguably the most influential film ever made

E4. The Kingdom of the Fairies (Le Royaume Des Fees) (Méliès, 1903) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

Many of Méliès’s 500-plus non-Moon films deserve a place in this gallery; this was chosen because some consider it his best, at least one considers it his “most intensely poetic,” and it is indicative of his post-Moon success: more stage machinery, rolling panoramas, miniature models, pyrotechnics, superimpositions, dissolves, and arguably, magic

Le Royaume Des Fees begins with a castle wedding where the prince and princess take vows and settle into new chairs as some sort of golem appears, gets physical with the lovers, and prompts the prince to beg him, but then jump up and beat the golem…into a puff of smoke? In the princess’s bedroom, six handmaidens in conical hats dress her for bed, place her in it, and leave her sleeping, which is when the golem reappears via stage trapdoor, touches the princess’s head, and calls forth a dragon-like carriage and six Selenite-like demons, who pick up the sleeping beauty, place her in the carriage, and push her away, just as the prince arrives, flails with his sword, and chases the demons offscreen as a dozen more pajama-wearing royals enter in a panic. On a Gothic castle balcony, the prince and other royals despair to see the demons move the bride up an unreachable ramp in the sky. A dozen royals clamor into a castle supply room, outfit themselves for battle, and leave how they came, with the prince coming up last…until the golem appears and magically alters the tableau to show demons using pulleys and ropes to haul the sleeping princess into a tower, which the prince attempts to stop, only to see the tableau return to his castle supply room, where the golem disappears and a magisterial fairy godmother appears and poofs the prince some kind of special helmet, sword, and shield. At a pier, the royals and our prince join nine lady sailors on a ship, but as it sails off for battle, the golem appears on the dock and laughs at them. On the open sea, horrible weather sinks the ship, which we see descend to the bottom. There, amongst the fish, squid, and passing mermen, a lead mermaid walks up to, revives, and escorts offstage the prince and three other royal soldiers. In the next tableau, an underwater cave, mermen and then four soldiers appear awkwardly riding fish and crabs as though they were horses. Several aquatic curtains give way to reveal Poseidon and his Botticelli-esque throne shell where several mermaids strike a pose just before the entrance of our soldiers, whose pleadings to Poseidon win them a whale, who enters, opens his mouth, patiently lets the soldiers enter his mouth, closes it, and drifts offstage. On the surface near a castle on an island, the whale opens his mouth, spouts his water, and watches as the prince and three soldiers scramble along the sea rocks. The prince takes off that helmet, sword, and shield to dive into the water near the island, but just as the golem appears to pursue him, the fairy godmother rises from the earth and points in the other direction, halting the golem and maybe the other soldiers. The prince arrives at the tower, sees the princess in a window waving a handkerchief, bashes in the door with a rock and big stick, and enters, but the golem appears, summons two demons with torches, and watches them enter and begin to burn the place. Inside, between the flames and smoke, the prince holds the princess in his arms and carries her outside. The prince scales the other shore’s cliff, delivers the princess to his colleagues, starts to join them, gets cut off by the golem, but then gets help from a suddenly appearing fairy godmother, who directs the prince to break the golem’s stick, which allows the prince to overpower him, stuff him in a barrel, and throw him over the edge. Soldiers bear the princess on a palanquin into the royal courtyard, where she is reunited with her father as the prince enters on a be-robed horse like a knight in 1000-year-old drawings. Cloud-curtains depart to reveal the final tableau, which changes all around the prince and princess as dancers dance and Greek-statue-like women stand at attention as petals fall and everyone seems to pose as though for a group photo.

The Kingdom of the Fairies was released a year after A Trip to the Moon; in the interim, Melies stayed busy making films and setting up pirate-fighting bases in a few countries, including the United States. Thus, The Kingdom of the Fairies was not seen by as many as A Trip to the Moon, and yet as an international hit, it probably earned Melies more money than his famous Moon film.

As with A Trip to the Moon, it is possible to read The Kingdom of the Fairies as a sort of self-aware, sarcastic critique of its main characters – in this case a modern twist on Sleeping Beauty. However, as with A Trip to the Moon, it seems likelier that most audiences, then and now, read the material without irony. For more than a decade, this film would stand as the first, and most famous, filmic representation of the honorable prince/knight rescuing the fair maiden from a tower.

Influenced by: Méliès’s previous films, his cumulative virtuosity

Influenced: Méliès created the land; everyone else colonized it

E5. The Great Train Robbery (Porter, 1903) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

Edwin S. Porter made cameras, film projectors, and related equipment until he lost his studio in a fire in 1901, when he took a job with the Edison Manufacturing Company as a cameraman. Porter saw British films from what would later be called the Brighton School, as well as films by Melies including A Trip to the Moon, and pushed Edison to make films more like these. One of Porter’s shorts, Jack and the Beanstalk, was clearly derivative of Melies; another one, Life of an American Fireman, was based not on Porter’s life but on a Brighton film called Fire!

The Great Train Robbery was based loosely on Scott Marble’s play “The Great Train Robbery,” which had been revived in New York in 1902. Porter also drew upon the 1901 Edison film Stage Coach Hold-Up as well as then-popular western lore on stage, screen, and pulp novels. The story may have also been influenced by the recent publicized exploits of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Porter did not really invent any of the film’s form or content, but he did put together the pieces in a dynamic, fluid, thrilling manner.

The film was shot mostly in November 1903, quickly edited, and released in December 1903.

As with many prints of A Trip to the Moon, The Great Train Robbery has about 14 shots and is about 11 minutes long, depending what speed the film runs and what counts as a shot. The Great Train Robbery opens as bandits break into a railroad telegraph office and tie up the train officer while a train moves outside the window. In the next shot, bandits force an engineer to fill the tender at the water tank. One train’s car rides with its door open, letting us see the outside whizzing by as bandits tie up an engineer, kill a messenger, and open a box of valuables including a bit of exploding dynamite. On top of the engine car, bandits fight and kill a fireman and force the engineer to stop the train. In a wide shot staged 45 degrees from the resting train car, the bandits fleece the passengers, except for one who jumps away and is shot dead for his trouble. The bandits escape in the decoupled locomotive and arrive at a remote forest. Back at the train telegraph office, a girl enters and pours water on the operator to revive him. At a dance hall, people are shooting not near a tender but near a tenderfoot to make him dance until the telegraph operator runs in to report the robbery and form a posse. The posse rides through the forest. In the final shot of the narrative, the posse catches up to the bandits and eventually wins the resulting shoot-out. In the actual final shot, not related to the narrative, we see the film’s only close-up, a bandit looking at the camera and firing.

After The Great Train Robbery was met with an enthusiastic reception, Thomas Edison heavily promoted and distributed the film. By the time of that summer’s St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, where the film played to full houses, The Great Train Robbery was a bona fide phenomenon and regularly given credit for aspects that Porter hadn’t himself invented. Still, the history of film is not only about innovations but also about reception and popularity, and The Great Train Robbery not only “mainstreamed” its style but also got people interested in the world’s first indoor theaters dedicated entirely to motion pictures – named nickelodeons because the program cost a nickel. The bandits in The Great Train Robbery may not have escaped with their loot, but the bandits behind The Great Train Robbery escaped with quite a few nickels.

Influenced by: Méliès

Influenced: all of pre-Hollywood American cinema

E6. The Consequences of Feminism (Guy-Blaché, 1906) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

Alice Guy-Blachè, the world’s first, and for at least a decade only, female director founded narrative film at the same time as Méliès, but most of her early work is lost or unreliably dated, though we know she pioneered many techniques, including close-ups, sync-sound, color timing, and effects.

All of Alice Guy-Blache’s early films are somewhat transgressive in form, but this was chosen for being equally boundary-pushing in terms of content. Here, Guy-Blache executes a creative approach to casting and plot, as women take on the traditional roles of men and vice-versa

The Consequences of Feminism begins in a very fin-de-siecle parlor where men are sitting around a table behaving in a way that Americans would have then called effeminate. One of the men, let’s call him Taylor, puts on makeup, picks up a suitcase, sashays out of the room, walks around “outside” near a cafe, and gets propositioned and touched by a woman who is interrupted by an apparently more chivalrous woman who escorts Taylor to a park bench, where she foists herself on Taylor while two other men walk by and hustle away without helping. Cut to a living room, where Taylor sews while his apparent father irons and his mother kicks her feet up, smokes a cigar, and throws her weight around. Mom and Dad leave just before the park bench woman arrives, relentlessly pursues Taylor for a kiss, follows Taylor into another room, and pushes him so hard that he faints, causing her to rouse him with smelling salts. Taylor’s mom, or someone looking like her, enters a saloon where all the women are being macho and, when a man comes around collecting laundry, the ladies pull clothes out of his basket and throw them at him while laughing until he runs away. Men begin to enter with children and babies but the women’s yelling and bluster scare them off. Outside again, men escorting children and babies greet each other and kids with kisses, although one woman, sitting at a cafe table, gets up and objects to a baby in a carriage (perhaps it’s crying), and the dad at first begs her forgiveness then hits her with a fruit, blinding her and causing her to fall to her knees as the other men and kids jeer her. Back at the saloon, Taylor enters, makes a righteous speech, and cues the entrance of other men, who corral the women out of there and then celebrate with bottles up – they have cleaned up this unsavory element.

This film is a nice reminder that the term “feminism” far predates second-wave feminism. Furthermore, most of Guy-Blache’s jokes here hold up fairly well.

Influenced by: the Lumières; pre-suffrage feminist culture

Influenced: Guy-Blaché directed something like 1000 films, and pioneered techniques that later became mainstream

E7. Humourous Phases of Funny Faces (Blackton, 1907) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

In 1896, J. Stuart Blackton was a 21-year-old reporter assigned to cover Thomas Edison’s Black Maria studio; after, Blackton decided to found his own studio, Vitagraph, which did well enough for Blackton to leave journalism. Around 1900, Blackton made a film called The Enchanted Drawing that some consider the first animation on film. If you watch this 90-second film, you’ll see why it’s not really the first animated film; Blackton himself is on screen the whole time, drawing a picture of a face on an easel; occasionally, the film stops and restarts so that Blackton can take the drawn wine or cigar and morph it into its real-life referent as the face looks put out. After that, Blackton made lots of other films, mostly live-action, most of which are lost. At this time, Georges Melies more or less perfected stop-action: stopping the camera as often as ten or twenty or thirty times for a sort of transformational shot that might not run back longer than a second or two. In 1905, Blackton and his colleagues more or less invented stop-motion animation, perhaps by accident, first by augmenting stop-action effects with bits of hand-drawn ghosts or toys. As an experiment, Blackton decided to go further with this idea than he had seen from Melies or anyone else, with a three minute film entirely “set” on a chalkboard, as it were. So was animation invented – more or less.

Humorous Phases of Funny Faces begins with a visible hand and chalk drawing a male face and a female face on a chalkboard. For a moment, the faces seem still, but at about the one-minute mark, they come to life, as the man grows hair and a cigar whose smoke drifts into the woman’s face, disturbing her. The cloud effect grows as the hand returns to erase this drawing and replace it with a full shot of a plutocrat with coattails and an umbrella. Cut into another cloud of erasure that becomes two new faces that steadily lose their lines, making clear that the film is running backwards. The film’s final tableau begins with a fully formed clown who begins acting like a Wayang puppet, moving his hat and arms and then manipulating a poodle through a hoop before the hand intervenes to erase his entire right side, but the clown continues to use his left side until the film ends.

Later animators did study this, but Blackton himself considered this film and others like it to be so sophomoric that he omitted these cartoons from his autobiography.

Influenced by: the Lumières and Méliès

Influenced: influenced or even founded animation, at least in America; Blackton considered it puerile, which should give current fans of animation some pause (but won’t)

E8. Fantasmagoria (Cohl, 1908) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

Emile Cohl was inspired by Humorous Phases of Funny Faces and sought to make a cartoon with both more and less of a plot – more activity, to be certain, but also a salute to the Incoherent Movement which basically privileged stream of consciousness over, uh, any possible stream of consequences. Each drawing was actually done twice, and there were about 700 of them, adding up to about 90 seconds of film.

Fantasmagoria begins with a hand drawing, on a blackboard, a clown who quickly gives way to a top-hatted gentleman who soon lands in an apparent nickelodeon, where he oddly dispatches the clown sitting in front of him – does the clown become a spider? – only to see the clown replaced by a lady with a large-feathered hat, feathers that the gentleman plucks off one by one. The clown somehow emerges from her now bare head and dispatches the gentleman along with the rest of the tableau as he transitions through more little vignettes with larger people, plants, a bottle, an elephant, a house, and an inkwell that lies the clown flat until the hands re-emerge to revive him and place him on a horse as he waves goodbye to us.

Some consider Fantasmagoria the first animated cartoon, because it’s more deliberate and motivated than Blackton’s animated experiments. One might also call it the first film on this list to really embody the “experimental” nature of many of this list’s later films in the sense of being intentionally abstract and even abstruse, or, one might say, mirthfully random.

Many later animators studied and copied it.

Influenced by: Méliès, Blackton

Influenced: this is a (perhaps the) foundational cartoon

E9. L’Inferno (Bertolini, Padovan, Liguoro, 1911) clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on youtube

“After the torture he tears the bandage from his eyes, hoping to see the light once more…In his despair he dashes out his brains on the dungeon floor.”

Why did the world’s first well-known, well-received feature film come from Italy? In the first decade of the twentieth century, all big Western countries saw their film industries grow and expand beyond anyone’s expectations. France, Germany, Britain, Russia, or the US, might have been, but weren’t, first with a daring, successful feature film. It sounds a little trite or stereotypical, but Italians seem to enjoy spectacle. Also, more than those other countries, Italy happened to have a lot of classical and Neo-classical “sets,” or at least locations, sitting unused. As nickelodeons first became a thing in Italy, in 1906, a faithful period short of Shakespeare’s Othello proved a big hit. In 1908, a short called The Last Days of Pompeii proved an even bigger hit. This gave a few Italian directors the impetus of an even bigger scale – and what better to adapt than an all-time world classic by an Italian?

Dante’s Inferno turned into Bertolini’s Fiasco – setting a record not only for cost but also time between preproduction and film print – almost three years. However, when the film became a hit, as you might imagine, film industries took the lesson that more means more – a credo they tended to believe even a century later.

Although this is the first film on this list to feature inter-titles, in fact the practice had become more common in the years just before this, as audiences proved receptive to them.

L’Inferno begins with a terrific logo, that of an apparent female filmmaker and “Milano Films.” The first title card says Dante is in a dark wood looking up “the hill of salvation” but we soon see him blocked by animals representing greed, pride, and lust. In a limbo filled with casually chatting toga-wearers, the angel Beatrice convinces Virgil to help Dante, and so Virgil disappears, reappears near Dante, mystically tames a nearby wolf, and escorts Dante through rocky terrain to the gates of hell with a sign saying, among other things, “all hope abandon ye who enter here.” After the duo enter a cave, they come to the river Acheron, where an old bearded man, Charon, shakes his fist at our duo and at the naked souls gathered on a river bank, some of whom he gathers and ferries to the other side, causing the screen to tint red. Virgil reassures a fearful Dante as they continue into limbo where they pass many recumbent, naked souls before meeting, per a card, Homer, Horace, Ovid, and Lucanus, who stand in handsomely designed togas, wave-salute their hands, and introduce Virgil and Dante to some of the many blameless celebrity souls who live without hope in limbo because they died before Christ was born. Virgil and Dante watch a becrowned, corpulent man, King Minos, assigning trembling souls to their next place as a nearby tar-covered, pitchfork-bearing devil smiles. In a rather remarkable shot, Virgil and Dante stand as hundreds of horizontal naked bodies swirl in patterns all around them – though the titles point out only women going to hell, like Cleopatra, Dido, and Helen. One, Francesca de Rimini, alongside her lover Paulo, floats to our duo and explains how she was reading about Lancelot and was cursed by a kiss – something we see in the film’s first “flashback” – causing Dante to collapse with pity. Virgil and Dante meet the three-headed monster Cerberus, who looks like a llama-shaggy dog, and Virgil throws dirt that Cerberus chooses to eat rather than keep blocking their way. Virgil and Dante, whom cards sometimes call The Poets, walk through recumbent Gluttons enduring torrents of tormenting rain. The Poets pass a cranky, behorned, soot-covered Pluto watching misers and spendthrifts, whom we soon see, naked, rolling bags of gold around a craggy ground. A card tells us that what we next see is a Stygian swamp of the slothful and wrathful. In remarkable composite shots, Phleguyas puts the Poets in a small boat, bound for Dis, and ferries them past many desperately gesticulating bodies toward the other side, which looks like demonic smoke over rocks. At the Dis castle-like entrance, the Poets are blocked by an evil horde of at least 20 “evil spirits” who Virgil somehow disperses only to see the sudden appearance of the three furies, who may or may not get disappeared by a fairy, or angel, allowing Virgil to escort a trembling Dante through the Dis gate. In a red-tinted landscape, the Poets walk by Heretics in shallow, sometimes fiery pits. At the burial place of Pope Anastasius, surrounding dirt clumps vibrate, resembling medfly groups. In a thinning forest, men in the branches are introduced as suicides. One of them, Peter Vigna, prompts the film’s second flashback where we see him in royal garb in a dungeon where authorities enter, read a parchment accusation of treason, watch Peter tear it up, seize him, and use tongs to poke out his eyes, which leads to an extended scene of him struggling with his bandage and apparently bashing his own skull in. Human-bird hybrids that the film calls harpies, as well as dogs, more or less attack the trees to Dante’s horror. In the next tableau, fireballs rain down near blasphemers. The next shot is of a monster, Geyron, a sort of griffin-dragon descending with the Poets on his back. Now, amongst craggy rocks, the Poets watch as soot-covered winged demons whip naked souls who genuflect gingerly through giant rocks. Next, rather hellish rock formations surround a river of filth where flatterers “and dissolutes” wash in vain to get clean. Next, a more red-tinted version of the same tableau, but this time, Summonists, who sold church goods, are upside-down in pits, flailing their feet while they’re singed by fire. We dissolve to a similarly steamy region of “boiling pitch” where demons torture people who misappropriated money. Ten of these sooty demons escort Virgil and Dante into the next, and similar, tableau, where a demon uses a pitchfork to lift Ciampollo out of the boiling pitch until he somehow distracts them enough to dive into the pitch where demons fail to get at him. The now frustrated demons lunge at Virgil and Dante, who fall off a cliff into another circle where those demons can’t go. In this rocky terrain, the Poets meet hypocrites, moving like slow monks, wearing gold cloaks that are actually lead, including one, Caiphas, crucified for his role in crucifying Christ. In another hellish area, a blaspheming robber speaking to Dante is attacked by one of the area’s many serpents, who watch along with the Poets as “grafters” and faithless accountants are approached by crocodiles and transformed into weird hybrid creatures. Perhaps the most infamous moment of the film is preceded by the title card, “The sowers of discord and the promoters of dissension maimed by demons. Mohamed with his chest torn open.” In that shot, several condemned people walk by holding their own body parts, including Mohamed, with entrails falling out of his chest. The next tableau brings “forgers, falsifiers, alchemists, counterfeiters changed into lepers.” Virgil and Dante walk by two giants being tortured and a third, Antaeus, who they command to pick them up and place them in the next ring, which he does, and they find themselves near his giant feet looking at traitors mostly encased in ice, and after they walk by dozens of heads in the ice sheet, they come upon Count Ugolino, who takes a break from eating another soul to prompt a flashback to the Tower of Pisa where we see an Archbishop force him and his kids and grandkids to starve to death. Virgil and Dante walk toward the end of the ice floe, where the 100-foot tall Lucifer chews on bodies – titles tell us they are Brutus and Cassius. After genuflecting to this monster, Virgil and Dante walk through a narrow cave passage until they arrive at the cave entrance, which they pass through with relief. The film ends with a shot of a memorial to Dante in Trento.

Whether or not L’Inferno is the first hourlong film, the oldest surviving one, the best-received one, or some combination, one can see its influence in many, many ways, from the heedless appropriation of non-copyrighted intellectual property to the reveling in blasphemy somehow dressed up as a pious act to the, well, hero’s journey of sorts. One reason it’s on this list is that it marshaled the many experimental effects that Melies had pioneered and proved that such effects could support and even justify an hourlong narrative.

Influenced by: Méliès; Gustave Doré’s art; pre-World War I morality

Influenced: its success let theaters raise prices and proved people would watch hour-long films (some screenings had two intermissions), though later it went unseen or censored for many years

E10. A Fool and His Money (Guy-Blaché, 1912) imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on youtube

“Sam begins spending his money.”

Guy-Blaché was so successful that she began her own trans-Atlantic production company, and here she used it to make (what was probably) the first fiction film with an all-black, or mostly African-American, cast. At a few moments in the film, we see a full shot of at least 12 African-Americans together, a sight that Hollywood films would not replicate, outside of a few musicals, for nearly 60 years.

In her parlor, Lily entertains her father and a beau, but when Sam appears at the door, Lily prompts the two men to bum-rush Sam. Walking away down the sidewalk, Sam comes upon a lost wallet, so he grabs it and runs. In his flat, Sam dances, smiles widely, writes an overconfident note, and decamps for New York. He acts like a fat cat in a jewelry store where he buys rings, a clothing store where he buys a tux and tails, and a car dealership, which he leaves via his new car helmed by his new chauffeur, who drives Sam to the house of Lily, who runs up to the car, drags Sam into the house, invites Sam in for tea, accepts his ring, and watches approvingly as her father slams the door on the former beau. At a party of at least 12 people, Lily shows off her new ring and Sam makes new acquaintances, two of whom invite him to poker, where they cheat and fleece Sam for much of his cash. In the larger party, Sam expresses his stress to Lily, who is happy to move on to the main poker cheater, who escorts Lily out of the house to a waiting car that the two of them climb aboard while laughing at the newly destitute Sam, who is seen one last time back in his flat eating a banana as the film ends.

This film is not entirely free of stereotypes, but it proved the viability of non-white actors onscreen, and was experimental in the sense of not relying upon white actors. Sadly this was mostly a road not taken; three years later, The Birth of a Nation was released, and its hurtful, vicious racism dominated filmic representations of black people for decades to come.

Influenced by: in some ways, only herself; in other ways, the long history of female allyship with POC

Influenced: Guy-Blaché trailblazed a world we can now take for granted

E11. The Cameraman’s Revenge (Starewicz, 1912) imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

“Mr. and Mrs. Beetle have too calm a home life. Mr. Beetle is restless and makes frequent trips to the city.”

Wladyslaw Starewicz had a career as both an artist and naturalist, interests that eventually led him to Lithuania’s Museum of Natural History. There, he made some of that museum’s first short documentaries, including at least one about insects. Starewicz wanted to make a film about stag beetles fighting, but was frustrated that under stage light, they slowed or stopped or even died. Around 1909, Starewicz learned of the work of Emile Cohl, for example Phantasmagoria, and that of Arthur Melbourne Cooper, who was clearly influenced by Cohl when he made Animated Matches. Starewicz re-created the stag beetle battle by replacing their legs with wire and attaching wax to their thorax, turning them into puppets. Thus did Starewicz make the world’s first animated-puppet film, Lucanus Cervus, as well as the first Russian animation film. This film is lost.

Encouraged by his friends’ enthusiasm, Starewicz next made The Beautiful Leukanida, about two male beetles fighting over a female. This film was hard to find for about a century until it was restored. The film of Starewicz that traveled and remained in circulation throughout the 20th century was The Cameraman’s Revenge, a film that flattered Europeans’ cynical sensibilities.

Mr. Beetle, larger and darker than Mrs. Beetle, packs his suitcase, smooches his wife, and departs his house in the backseat of a cricket-driven car. At a club, “The Gay Dragonfly,” after a grasshopper seduces a performing dragonfly right off the stage, Mr. Beetle pushes aside the grasshopper, followed by a card that says Beetle should have known the aggressive insect was a cameraman. The grasshopper puts his camera and tripod on his motorcycle, follows the new pair to the Hotel Amour, follows them up the hotel’s stairs, films them inamorata through the keyhole, and gets noticed, knocked down stairs, and forced to flee. A card says “Mrs. Beetle is also restless. Her friend is an artist.” Bea Beetle sends her maid with a note to the studio of a cricket painter who, elated at the news, picks up his large painting of Bea and decamps. Bea’s maid makes a fire in the Beetles’ fireplace in front of which Bea falls asleep, but when her painter arrives, she joyfully kisses him. When Mr. Beetle arrives to see his front door locked, he breaks it down with his briefcase. Hearing him, the cricket escapes into the fireplace just before Mr. Beetle arrives, finds the cricket’s hat and painting, and bashes them over his wife’s head. The cricket emerges from the chimney, falls down the roof, and lies near the front door tired as Mr. Beetle emerges and fights him until the cricket absconds. A card tells us “Mr. Beetle is generous. He forgives his wife and takes her to a movie.” At the movie theater, the projectionist, who is the grasshopper, plays the incriminating footage, which causes Mrs. Beetle to beat Mr. Beetle with her umbrella until he jumps through the projection screen. Mr. Beetle finds the grasshopper in the projection booth, knocks him down a ladder, and burns down the booth. A card says it hopes the Beetles’ home life will become less exciting. The final shot shows Mr. and Mrs. Beetle in prison, getting used to each other again.

The nature of cinema gives immortality to the mortal, but few films animate the dead quite like this, which astonishes every first-time viewer. What exactly does it mean to see dead insects enact these human foibles? More than a century later, it’s hard to say why it remains so affecting, and that must be part of why it does.

This is precedent to the likes of Wallace and Gromit and Nightmare Before Christmas – which makes sense, since Starewicz made a version of The Night Before Christmas

Influenced by: Blackton, Cohl, Cooper

Influenced: pioneered stop-motion animation; thematically rich and not for kids, this cleared the way for other adult-targeting animators

E12. Gertie the Dinosaur (McCay, 1914) imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

“I made ten thousand cartoons, each one a little bit different than the one preceding it.”

History buffs are familiar with the fact that we do not always know the year of a given luminary’s birth, and in that case, the birth year might be listed as “circa 1900 or 1901.” I’ve never seen a larger gap in the record than the one for Winsor McCay, whose birth is listed as circa 1866 to 1871. At the turn of the century, the boyish-looking McKay found employment in what was then considered a juvenile medium, cartoons, and worked his way up to the New York Herald, where he became best-known for the Little Nemo strip and some political cartoons. McCay found he could supplement his income by giving what he called “chalk talks,” vaudeville or stage performances where he drew on an easel with such efficiency and acuity that he seemed to be manipulating the drawings like puppets.

In 1911, McCay left the New York Herald over money, taking Little Nemo to the New York American, although a court ruled that the Herald could let another artist do his Little Nemo, and it did. During this same time, McCay claimed to be inspired by flip books that his son had brought from school, and he turned his Little Nemo into one of the world’s first animated cartoons. As it ran in nickelodeons, the short was mostly live-action set-up and then, finally, the characters mostly stretching. For his next animated short, McCay eschewed setup and inter titles and, in How a Mosquito Operates, simply showed a mosquito setting himself up on a sleeping man’s face. One could make the case that this is the film that should be on this E-list, although then 1912 would be represented only by cartoons about bugs. More importantly, it was his next film that was his most renowned, influential, and, in many ways, experimental. Legend has it that some accused McCay of tracing a real mosquito, so he responded by centralizing an animal whose movements could not be traced.

Strange that McCay would bill himself as “the first man in the world to make animated cartoons,” when these were made under the direct supervision of J. Stuart Blackton at Vitagraph, director of Humorous Phases of Funny Faces and the arguable bearer of that honorific. Nonetheless, McCay may have been onto something, because his cartoons were much closer to what the medium eventually became, and not only because of its lovable plushie-ready leading animal. The 5 animated minutes of Gertie the Dinosaur were the first to use keyframes and registration marks, or what they then called in-betweening, drawing the major frame “shots” and then filling in the gaps with more routinized loops. It was also the first to use tracing paper and the Mutoscope action viewer.

To summarize the film is awkward, because we are mostly concerned with its five animated minutes, yet audiences saw a 13 minute film. The first 7 minutes are a self-reflexive setup in which Winsor McCay hangs out with fat cat artists who, one day, go to a museum and bet that no one can make a dinosaur come to life. As with the Little Nemo film, this film stresses the necessary thousands of drawings by stacking them in piles like office work, although here, onscreen, McCay carries and then drops a human-sized stack of papers. At a dinner of plutocrats, McCay stands in front of an easel which finally takes up the film’s entire field of vision as the animated Gertie the dinosaur pokes her head out of a cave and comes into the foreground near a lake. The brontosaurus eats a rock and a tree and, cued by McCay’s voice (rendered as titles, because it’s a silent film), lifts her feet in turns and often swivels her head. When her look at a sea serpent makes her ignore a direction, McCay calls her a bad girl, causing her to cry. When a mammoth walks in front of Gertie, a card warns her not to hurt Jumbo, but she uses her mouth to pick up the pachyderm by its tail and hurl it into the lake, from which it watches her dance, sprays her with water, escapes, and almost gets hit by a rock she throws. A dragon, or perhaps four-winged lizard, flies by. A card encourages Gertie to get a drink, and she winds up slurping up the entire nearby lake. McCay himself, as an animated figure, enters the frame, and gets on Gertie’s back for a little ride out of the frame. Back in the live-action lunch, the plutocrats pay off the, ahem, real McCay.

Influenced by: Blackton, Cohl, Starewicz, McCay’s earlier work

Influenced: Walt Disney and his generation; this film laid out the template for commercially successful animation; El Apostol would become the first animated feature, but is lost

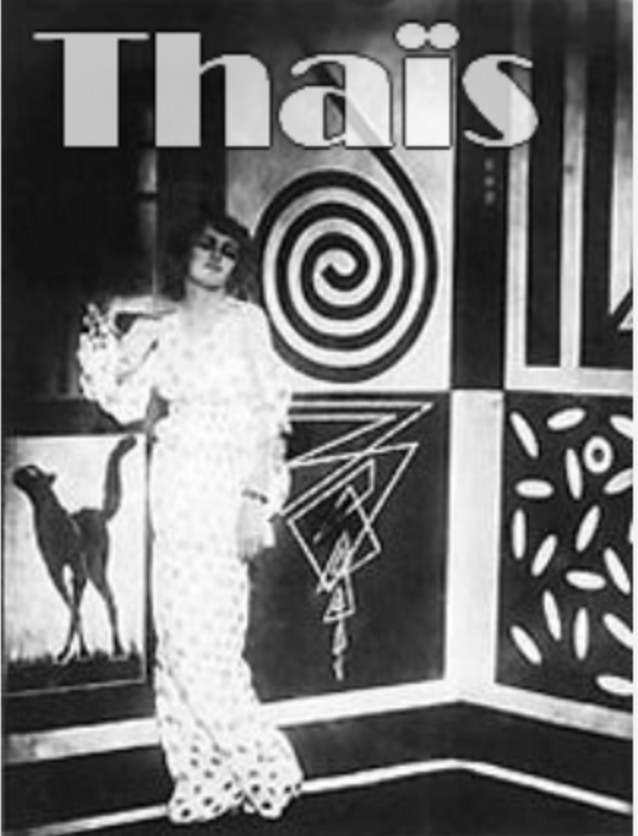

E13. Thais (Bragaglia, 1917) clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

Anton Bragaglia had theatrical brothers and got a job as an assistant director in 1906 with Italy’s nascent film industry. The industry and Bragaglia grew up together, and a year after L’Inferno came out, in 1912, Bragaglia felt emboldened enough to publish a manifesto called Fotodinamica Futurismo about the sort of futurist photos and art that the world needed. Already, Picasso’s Cubist works were famous and Germany’s painters were experimenting with what would later be called Expressionism. The outbreak of the Great War interrupted him for a while, but then seemed to add to the urgency by 1916, a rather busy year for Bragaglia, when he founded an avant-garde magazine, wrote another major manifesto, and created a film studio that would exemplify these futurist works.

Thais was Bragaglia’s first attempt at a full-length avant-garde film and apparently his only surviving such film. For the film, Bragaglia centered Prampolini’s paintings, anti-realistic acting, and modern dance. He knew audiences would be more likely to accept such things in the context of a story that also featured outdoor shots of a picturesque estate, with that estate’s rich people in contrast to Thais, who could be eccentric in manner and taste.

Cards tell us the film includes images by Futurist painters to strengthen the classic narrative in order to evoke in the viewer stronger emotions than those created by mere film images. We meet Véra Probajenska, nicknamed Thaïs, a young countess dancing in front of doors and walls of unusual patterns. We cut to plutocrats puttering around the outdoor grounds of a large estate. Thais invites Count San Remo to her studio decorated in accordance with the most decadent art principles. After several subversively decorated rooms, Thais shows San Remo the secret Gate to the Mysterious Beyond where she says will escape when she will have lived enough. Thais goes riding with her friend Bianca, Count San Remo and her cousin Oscar during the day. That evening, Thais hosts a crazy dinner party. Bianca is apparently in love with Count San Remo while he only has eyes for Thaïs. Wearing an exotic dress, Thaïs is having tea with the Count when Oscar arrives with flowers. Thais sends him away, planning to drive the Count crazy with her flirtation.When the Count tries to kiss her, she sends him away as well. When Bianca arrives, she tells her that she doesn’t care for the Count and that Bianca can have him if she wants. At Thais’ place on another night, Thaïs continues her flirtation with the Count. When Bianca comes to his place, she finds the Count at Thaïs’ feet. Bianca decides to say farewell to Thaïs, but the latter mocks her and says she’ll come back soon. Bianca asks for a dangerous horse to be saddled for her. Out on the more normal-looking palace grounds, Bianca goes riding and is mortally wounded in a fall. Thaïs feels guilty for having taken away the Count from her. She sets in motion the plan she had arranged for her death, the film becomes markedly abstract, and Thais probably suffocates, delirious, in the fumes of fatal perfumes.

What survives of Thais is fragmentary and sometimes hard to watch, but it clearly blazed a trail that many avant-garde artists would follow.

Influenced by: then-modern art of many types, futurism

Influenced: German Expressionism, other futurism

E14. Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (Weine, 1920) clip imdb LB RT trailer wiki

stream on criterion

“What she and I have lived through is stranger still than what you have lived through. I will tell you about it.”

Is there a longer wiki on any film than on The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari? I only ask because those 220 footnotes are a great place to start. Like many other film instructors, I’ve been teaching this film for years, so how to summarize and synthesize everything into a few sentences here? Well, start with the fact that what we now call German Expressionism existed before the Great War in paintings and literature. In terms of cinema, Italian futurists were a partial inspiration, but so was the work of German filmmaker Paul Wagener. It’s not clear that unemployed, penniless writers Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer knew much about this work when they wrote The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in 1918; instead they cited Freud, psychology, medieval legends, and their own lives, for example the government’s psychological interviews of Mayer when Mayer avoided military service by claiming insanity.

Accounts differ, but probably, the head of the Decla-Film studio, Erich Pommer, was instrumental in not only buying the script but also turning it into a bold experiment – Pommer would later say that the way they filmed was cheaper than constructing more realistic medieval sets. The production designers were Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Rohrig, and they all encouraged what we see – sharp-pointed forms, oblique and curving lines, leaned and twisted structures, shadows and light streaks painted on sets. Arguably, under Robert Weine’s direction, the artists were just looking for visual referents to dementia or loss or insanity; they weren’t trying to create the ur-text of German Expressionism or likely the most influential of all radically experimental films. Yet they did.

A young man, Francis, sitting in a garden, tells an older man that he sees spirits, possibly including a dazed woman walking by them. Francis begins to recount Hollstenwall, a village that looks oddly bent and misshapen. A fair arrives, including a large man in a top hat, Dr. Caligari. Alan and Francis, who live in an apartment without right angles, walk to the fair down a street without right angles. Caligari gets a permit to display a somnambulist, but the clerk criticizes the idea and gets killed that night. In the oddly angled town, the fair commences and Caligari tells a crowd about Cesare, the somnambulist, who may wake for the first time in 25 years when he theatrically opens his cabinet, or coffin. At Caligari’s command, Cesare awakens, steps out of the cabinet, and answers Alan’s question, “how long will I live?” by telling Alan he’ll die at dawn. While the town searches for a murderer, Alan and Francis woo Jane but promise to stay friends. Creepy imagery of a night shadow creeping into Alan’s room is followed by Francis receiving news that Alan was murdered. Jane and Francis tell the local police while a shadowy figure staggers down oddly painted stairs. While police arrest a shady-looking man, two other detectives enter Caligari’s trailer, find Cesare hidden in the cabinet, and are about to awake him when they all get the news that the killer has been arrested. After the men leave, Caligari laughs and soon directs Jane to behold Cesare, standing in his cabinet. That night, Cesare slithers toward Jane’s room, clinging to the walls as though the floor is lava. After she struggles, Cesare carries her around some of the most unusually shaped parts of the town. With a mob in pursuit, Caligari lets go of Jane, staggers away, and then collapses. When Jane tells Francis Cesare kidnapped her, he refuses to believe her, walks to Caligari’s house that he’s been watching, storms in, and opens the cabinet to find…a dummy of Cesare. Caligari runs away as Francis follows him through the odd streets into a mental asylum, where Francis learns…that Caligari is the asylum’s director. Francis and several white-coated asylum employees search through the local books and learn – as we see partly through flashback – that the asylum’s director read about a mystic named Caligari who controlled somnambulists and tried to become Caligari partly through manipulating Cesare. When Francis and staff confront the director, he falls on Cesare’s corpse, stands, attacks a staff member, and gets subdued and then strait-jacketed, an inmate in his own asylum. Back in the frame story, or the present, Francis finishes as we see that he is in fact an inmate in an asylum that also contains the living Jane and Cesare, who look harmless if uninterested in Francis. When Caligari appears as a very normal looking museum director, Francis freaks out that he will kill all of them, but after the staff subdues him, the director says now that he knows Francis thinks he’s Caligari, he knows how to cure him, and the iris comes in on his last knowing look.

In certain quarters, people are still arguing over Siegfried Kracauer’s book “From Caligari to Hitler,” one of the first books that ever took cinema seriously, and one that argued that Germans’ pathology and love for irrational authority was somehow evident in the Caligari film and throughout the Weimar era before Hitler came to power. Kracauer’s thesis has been quite assiduously contested, not least because the frame story may well have been grafted on somewhat late in production. Does the frame story, which may have been suggested by Fritz Lang, make the film more conformist, more radical, or what? Not going to get into all that here, but more than a century later, it’s amazing that the film survives and maybe even encourages contradictory readings of itself.

Lotte Eisner’s book The Haunted Screen remains perhaps the best single text to understand the scope and scale of what the film is and became. But to over-summarize, let’s say that in the context of its period, quality, and success, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari amounts to the largest-ever attack on “realism”; it also established cinematic German Expressionism and, per Roger Ebert, the modern horror film.

Influenced by: German Expressionist art in other mediums, especially painting and theater; Griffith-esque films as contrast

Influenced: by establishing that great cinema does not need naturalism, this has to be counted one of the most influential films ever made

E15. Manhatta (Strand and Sheeler, 1921) imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

“When million-footed Manhattan unpent, descends to its pavements.”

The opening title card begins, “City of the world (for all races are here). City of tall facades of marble and iron. Proud and passionate city.” Shots of the city give way to a ferry carrying what look like thousands of commuters, who pour into the city, dominate the sidewalks, and thin out in front of a large building, leading to another card praising iron height. We watch construction workers assembling the foundations of the next mammoth. From higher floors, we see industrial steam rising from various edifices. From even higher floors, we see ships in the East River looking like toy boats. Trains and ships belch smoke, intertwining abstractly. The vertiginous perspective renders strange the rails and workers below. We see several Brooklyn ferries and then read a quote from Crossing Brooklyn Ferry that…weirdly doesn’t name the poem or its author, Walt Whitman.

This is a short documentary about Manhattan, but it is often called the first American avant-garde film because it is structured in a rather abstract fashion, including intertitles that quote Walt Whitman without naming him; pioneer of the “city symphony” subgenre

Influenced by: stirrings in documentary from America and avant-garde (or “absolute” or “pure”) cinema from Europe

Influenced: city symphony documentaries; abstract American films

E16. Fievre (Delluc, 1921) clip imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

Louis Delluc began his career in film criticism in 1917, writing for several periodicals before making the leap to filmmaking. He was influenced by Abel Gance, but wanted to push the medium further than Gance had.

Fievre begins by cross-cutting, with many iris-outs, dock scenes of boats with pub scenes of locals drinking and playing cards. Women share drinks and stories of being with men. One barmaid goes to a supply room for more beer, where she fends off a man hitting on her. Right off a boat, a group of sailors come into the pub with their layers and bags and even a small monkey. A group of apparent, uh, prostitutes enter the pub and flirt with the new arrivals. One man describes, and the film flashes back on, his time in what looks like an Asian opium den. One man begins playing music and several of the men and women pair off dancing. The main barmaid watches skeptically, but finally approaches the storytelling sailor, who flashes on a picture of kissing her without actually doing it. He recalls a time he was sick in bed while an Asian woman cared for him, repelling and then attracting the barmaid. When a hatted man tries to assault a woman on the floor (she seems to be legless), the main sailor attacks this man, causing a fight that the main barmaid tries to stop by forcing the legless woman to say something. When that fails, the barmaid falls over her new beau’s broken body. Other sailors go into the alley and beat up the assailant. The seemingly paraplegic woman manages to rise to the occasion and pick up a flower in a vase off of the bar while the main barmaid leaves her beau’s dead body and walks off with police.

Several avant-garde filmmakers cite Delluc in general, and Fievre in particular, for inspiring them to focus less on plot mechanisms and title cards and more on emotion and feeling. No one film can be said to have begun the filmic French Impressionist movement, but Fievre comes as close as any.

Influenced by: filmmakers like Abel Gance

Influenced: innovative films of the period

E17. Lichtspiel: Opus I (Ruttman, 1921) imdb LB RT wiki

stream on youtube

After the success of Dr. Caligari, which needed a certain kind of music to make it make sense, the German film industry did what other countries’ industries had already done and made it routine for music sheets to be sent along with film reels. This opened a possibility for Walter Ruttman’s idea of a film that would be all music – well, shapes set to music. Again, it’s the early 20s, and every film is silent – but almost no film is experienced silently. Ruttman fashioned his film to be screened with very specific Mozart music played at a specific tempo.

Lichtspiel: Opus 1 begins with colored balloons apparently inflating in blackness. More fragmented colored shapes, many resembling falling paper, dance across the blackness. Sharper triangles and jagged leaves also poke or drift in and out of the darkness. Yellow globules make their way across the lighter background until they are seemingly threatened by orange triangles. White shapes take a turn. Blackness for a moment gives way to shapes swinging like pendulums. White boxes fall rapidly in a left-right pattern. Some kind of paisley shape slithers to and fro. A sort of light beam changes colors and swings back and forth from the top middle. The film ends with a red tear blob becoming a big red circle, almost as though the last shot is of the flag of Japan – except, with a black background.

This, a series of shapes moving on blackness set to music, was the first color abstract film as we now think of the concept, the cinematic equivalent of then-groundbreaking work of people like Picasso, Matisse, and Miro, the catalyst to other avant-garde work of the 1920s, and predecessor of everything from Fantasia to music videos

Influenced by: then-daring paintings; the Great War; animation experiments

Influenced: besides the wide influence already mentioned, Ruttman went on to make seminal avant-garde films and documentaries; he also served as Fritz Lang’s DP on Die Nibelungen and Metropolis

E18. Rhythmus 21 (Richter, 1922) clip imdm LB RT wiki

Hans Richter was a German artist who began by working at journals and in museums in the early years of the century. He liked the newer, bolder experiments, and came to advocate expressionism and Cubism even before the Great War. After he was wounded and discharged from that war, Richter returned to Berlin determined to oppose the war through art. After some of those experiments failed to gain much traction, Richter decided that abstract art was its own kind of anti-war revolution of consciousness.

Richter claimed that Rhythmus 21 was inspired by the desire to communicate the feeling of abstract art in a filmic format. He called it “absolute film,” as though he was the first to essay cinema’s absolute essence. For the remaining 55 years of his life, Richter also claimed that Rhythmus 21 was the world’s first abstract film, but there were Italian experiments – now lost – as well as Richter’s countryman Walter Ruttman’s film Lichtspiel. Whether or not Richter actually saw these, his film was often received as the world’s first abstract film and thus a marker of influence.

Frankly, Rhythmus 21 defies an easy summary of its sequencing. Basically, white parallelograms rise, fall, move left, move right, grow, shrink, and mingle amongst other white parallelograms to the dirge-like music. Compared to Lichtspiel, Rhythmus is, perhaps paradoxically, less reliant on rhythm or Fantasia-esque tableaus of beauty in motion; instead, this film is more deliberately dissonant, although not without harmonies.

More than a century later, it’s hard to appreciate just how radical Richter’s intervention was, whether or not he had seen other avant-garde films. Any modern museum goer has seen plenty of canvases that look empty, or nearly empty, causing some snarky tourists to comment that they could submit a blank white canvas and become a millionaire. In 1922, no one had seen such a thing even hanging on a wall. Thus, Richter’s film does count as a transformative break, a prompting of feelings and thoughts that no film had really attempted. Was it absolute film? In any event, it was absolutely radical for its time.

E19. La souriante Madame Beudet (Dulac, 1922)

Germaine Dulac was born in 1882 in Amiens, France, but her father’s upper ranks in the French military resulted in her spending much of her childhood in Paris. From a young age, Dulac showed interest in, and aptitude for, music, painting, theater, socialism, feminism, and journalism, writing for Paris feminist journals starting at the fin-de-siecle.

Eventually, writing about the theater awakened her interest in film. In 1915, with most of France’s men off to war, Dulac and her friend, writer Irene Hillel-Erlanger, founded D.H. Films, which over the next half-decade produced about a dozen films written by Hillel and directed by Dulac. 1920 was a big year for Dulac; she divorced her husband of 15 years, met Marie-Anne Colton who became her lifelong companion, and met Louis Delluc and collaborated with him on Le Fete Espagnole, considering a groundbreaking Impressionist work. Afterward, Dulac tried more and more experiments, in many ways culminating in La Souriante Madame Beudet.

The film begins in a provincial town where, we’re told, passions roil behind facades. We meet Madame Beudet as she plays piano and signs her name to Claude Debussy’s music sheets. We meet her husband, a cloth merchant, who comes home, sits next to madam, fiddles with threads, and opens a friend’s letter that offers the couple tickets to a Faust show. Madame Beudet turns down the idea, then fancifully imagines the Faust show, the purchase of a new car, and a handsome tennis pro carrying away her truculent husband. Mr. Beudet opens a drawer, sees a gun, laughs, and prepares a fake suicide note. On the phone, Mr. Beudet reaches a rather oddly behaving couple, who soon dress formally and come over to the Beudet house for the theater tickets. After a few dissonant moments, Mr. Beudet holds a gun to his head, but isn’t fooling his wife or the visiting couple, whom he soon leaves with. In her parlor, Madame Beudet reads “The Lovers’ Death,” which mentions sofas as deep as graves and prompts some unusual visuals. When the maid asks for permission to see her boyfriend, Madame Beudet visualizes a ghostly man hovering over her maid before she approves. Alone in her parlor, Madame Beudet’s thoughts are presented via enigmatic, abstruse visuals. She imagines Mr. Beudet, creepily grinning from ear to ear, entering via the window and behaving oddly around their house. A title card tells us the night has brought disturbing dreams and also passed. Madame Beudet apparently awakens to see her husband asleep in a nearby chair, but she is tormented by curious images and noises, like horses drawing carriages. Mister tries to kiss Madame, but withdraws at her withdrawal. We see a strange man with a cat walking downstairs and throwing fabric around. Alone, Madame Beudet rises, brushes her hair, lets in a cat, brings the cat into a hug on her bed, and throws the cat away. While Madame aimlessly brushes her hair, Mister looks around the place for a bill, instead finding and laughing at sheet music. Mister Beudet tells his friend that a woman is like a doll as he crushes a doll into his pocket. Madame Beudet tells the maid something important – we aren’t told what – but when Mister returns home to find Madame missing, the maid tells him to call his mistress. As Mister reviews the home expenses, Madame shyly enters as Mister brandishes the gun at her, tells her she deserves to be shot, and shoots a real bullet, scaring the cat and Madame. Mister hugs his shaken wife while asking if this means she tried to kill herself. She doesn’t quite answer as a card reminds us we don’t know what goes on behind these quiet street facades.

La Souriante Madame Beudet is not the first French Impressionist film, but many of the others are lost, and the fact that Beudet is not speaks to its reception and influence. Dulac created a story that was just realistic enough while also somewhat fanciful and transgressive. Although people weren’t really using “surrealism” to describe any films yet, one can easily see how Madame Beudet influenced much of what would later be called surrealism, from Salvador Dali to David Lynch.

E20. Return to Reason (Ray, 1923)

Although Man Ray spent most of his career denying this, he was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in 1890 in Philadelphia to Russian Jewish immigrants who wanted him to work in their garment business, but reluctantly allowed him, as a young man, to set up his room as an art studio. Arguably, tailoring left a lasting imprint on Man Ray’s eventual art. In the early 1910s, Man Ray worked occasionally as a professional artist and also took classes that turned him toward the nascent avant-garde, like that of Alfred Stieglitz, Pablo Picasso, and Marcel Duchamp, the latter of whom Man Ray befriended. Somehow, Ray and Duchamp both avoided military service, and instead promoted Dada and other radical approaches, like turning ordinary objects into art. In July 1921, Man Ray moved to Paris and immersed himself in the avant-garde scene. Man Ray managed to make enough money to afford to make a two-minute film, which he hoped would be like some of his paintings and sculptures come to life.

Return to Reason begins with a full cloud of vibrating pixels. It cuts between a shaky sundial, silhouettes of nails, and lattices of shadows that feel like full skies of black robot birds, or maybe TV static before that was a thing. Circles precede the film’s first shots of something like normal life – the lights of a carousel at night, rendered into abstraction and obscurity. An enigmatically ornamented title card reads dancer, or maybe danger. More abstract imagery flies across the screen in a manner that can only be described by freeze-framing. The camera may climb a sort of rope to arrive at a sort of dangling double-hashtag. Through fragmented, watery light, we watch the naked chest and torso of a woman with arms raised.

As a title, Return to Reason is probably meant ironically. Perhaps no preceding film had been quite so unreasonable. Following Manhatta and Rhythmus, Return to Reason more than doubles down on scattering randomness and playfully nonsensical imagery. More than its precedents, Return to Reason establishes the lightning-quick and mercurial attention span of the avant-garde.

E21. Sherlock, Jr. (Keaton, 1924)

Of all the American film creatives of the first half of the twentieth century, none was more revered by avant-garde artists than Buster Keaton, and no film directed solely by Buster Keaton was more revered than Sherlock Jr. Keaton has many envelope-pushing films, but Sherlock Jr. makes a fine introduction for the uninitiated, for reasons that will become clear.

By 1924, Keaton was a somewhat established film artist who could afford to take some chances. In the case of Sherlock Jr., some of these included hiring his disgraced former partner, Fatty Arbuckle, as well as doing some particularly injurious stunts, both chances that Keaton would come to regret. During editing, Keaton came to think the film was overlong, and trimmed it to 45 minutes, prompting his producer, Joseph Schenk, to beg Keaton to restore it to an hour to satisfy current consumer expectations. Keaton refused and wound up with one of his few non-hits. However, later history more than vindicated the decision.